“Tell me, Muse, of the man of many ways, who was driven far journeys, after he had sacked Troy’s sacred citadel.”

It is nearly 20 years after the Trojan War and Ithaka is still without its king, Odysseus. Anarchy reigns, as numerous suitors vie for the hand of his wife, Penelope, while ravaging his household goods and disrespecting his memory, and his son, Telemachos, is helpless to prevent them. Has our hero perished in his quest to reach his homeland, or is he still alive somewhere, struggling to reach home?

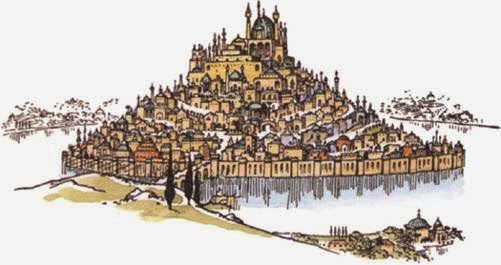

The Odyssey begins in media res, or in the middle, where Odysseus is near the end of his journey, becoming shipwrecked on the land of the Phaiakians. These people, who we learn are very close to the gods, give Odysseus an audience for the retelling of his story and the various adventures he has experienced, while attempting to return home from the battlegrounds of Troy.

From a violent assault on the land of the Cicones, to narrowly escaping a drugged existence in the land of the Lotus-Eaters, Odysseus endangers his men by deciding to stay in the land of the Cyclops in hopes of gaining host-gifts, and they must set to perilous flight. Poseidon, angered at the maiming of his Cyclops son, Polyphemus, plots their suffering and Odysseus and his men must endure captivity by Circe, an island goddess; a trip to the land of the Dead; a narrow escape from the Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis; and further imprisonment by the nymph, Calypso, lasting seven years, before he is released and lands on the island of the Phaiakians. Yet, mainly because of the rage of Poseidon, but due also to Odysseus’ and his men’s misguided judgement, his whole crew is killed on the way home and he is left to continue the final part of his journey alone.

Fame and glory, or in Greek, kleos, are the most important values in this society. It appears that the suitors can disrespect and commandeer Odysseus’ household, only because there is no story attached to his fate. If he had died fighting in Troy, and therefore receiving a generous helping of fame and glory, this inheritance would have passed down to Telemachus, which would have engendered a reverence and respect among the people. It might not have prevented a few of the more aggressive suitors attempting to utilize their power, but Telemachos certainly would have received more support and sympathy from other Ithakan families. Gifts and spoils are another aspect of fame and glory. The more one acquires, the more renown is added to their reputations. This perhaps explains why Odysseus pours on the charm with the Phaiakians, who bestow on him more gifts than he could have won at Troy, then taxi him to Ithaka, unaware that they have angered Poseidon, who turns their ship to stone in the harbour on their journey back.

The guest-host relationship, or in Greek, xenia, is another aspect of Greek culture unfamiliar to modern readers. If a guest visits your house, you are required by the tenets of hospitality to give him food and shelter. These acts are even more important than discovering his name and peoples, as we often see this information offered after the initial formalities are served. The concept of xenia is emphasized because one never knows if one is hosting a man or a god. As a modern reader, it was amusing to see poor Telemachos attempt to extricate himself from Menelaos’ hospitality and avoid Nestor’s, in an effort to avoid wasting time in the search for his father. I’m certain amusement wasn’t Homer’s intention but it wasn’t surprising as to the emphasis placed on this tradition. Any deviation from this custom could result in dishonour and a possible feud with your potential host or guest.

|

| 1. Mt. Olympus 2. Troy 3. Kikonians 4. Lotus-Eaters 5. Cyclops 6. Aeolia’s Island 7. Laestrygonians 8. Circe’s Kingdom 9. Land of the Dead 10. Sirens 11. Scylla & Charybdis 12. Kalypso 13. Ithaka source Nada’s ESL Island |

Greek literature has been a surprising passion of mine. From my first read of The Iliad, I was hooked and I often wonder why? The heroes are chiefly concerned with fame, glory, reputation, pillaging and the spoils of war; the gods are jealous, capricious, vindictive and possess far too many human traits for comfort. Yet I think what draws me to these characters is that they are so real …….. fallible, vulnerable, imperfect, yet they exhibit these deficiencies through an heroic, courageous and larger-than-life persona. They have their customs and traditions, institutions designed to help their society flourish, and which are important enough to sacrifice happiness, comfort and, at times, even their lives, to preserve.

The Odyssey Read Along Posts: Book I & II / Book III & IV / Book V & VI / Book VII & VIII / Book IX & X / Book XI & XII / Book XIII & XIV / Book XV & XVI / Book XVII & XVIII / Book XIX & XX / Book XXI & XXII / Book XXIII & XXIV

A note on translations: if you plan to read only one translation of The Odyssey, I would highly recommend Richard Lattimore’s translation, as it is supposed to be closest to the original Greek, while also conveying well the substance of the story. Fitzgerald is adequate but likes to embellish, and the Fagles translation …….. well, as one learned reviewer put it, “they are so colloquial, so far from Homeric that they feel more like modern adaptations than translations.” I would have to agree.

For people who are interested in introducing their children to the tales of Homer, there are a number of excellent books for children which I will list here:

- The Iliad for Boys and Girls – Alfred J. Church

- The Odyssey for Boys and Girls – Alfred J. Church

- The Children’s Homer – Padriac Colum

- Black Ships Before Troy – Rosemary Sutcliff

- The Wanderings of Odysseus – Rosemary Sutcliff

This book counts as Plethora of Books Classic Club Spin, so I finished her book and my spin book, as well. I’m going to give myself a pat on the back and less guilt for not finishing my previous spin book (yet). 🙂

Translated by Richard Lattimore

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)