“The city of Babylon, ‘the beauty of the Chaldees’ excellency,’ ‘the lady of kingdoms,’ lay quiet under the silvery splendor of an oriental moon.”

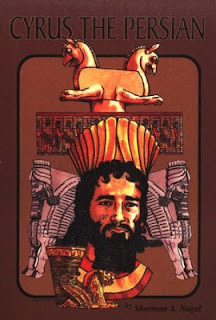

I just finished reading Herodotus’ The Histories, where the story of Cyrus figures prominently, so when Amanda at Simpler Pastimes Children’s Classic Literature Event appeared for April, I thought what better time to read a children’s book about the same historical figure?

Nagel sets the story of Cyrus in the time of the Jews captivity in Babylon, and their story runs parallel to that of Cyrus before the two intersect. One hundred years before Cyrus’ birth, the prophet Isaiah named him as the man who would permit the Jews of Babylon to return to their homeland to rebuild Jerusalem and the story allows us to be a part of events leading up to the fulfillment of this prophecy.

|

King Astyages sending Harpagus to kill young Cyrus

Jean Charles Nicaise Perrin

source Wikipedia |

The grandfather of Cyrus, Astyages king of the Medes, is visited by a disturbing dream and his magi tell him that he must destroy the child of his daughter, Mandane, if the child she bears is a boy. At Mandane’s marriage to the Persian king, Cambyses, Astyages extracts a promise that she will return to him before she gives birth to her firstborn and the promise is fulfilled as Cyrus is born in the kingdom of the Medes. In fact, so crafty is Astyages that he persuades the parents of Cyrus to leave him with his grandfather, and then sends for his trusted servant Harpagus, commanding him to kill the child. At the notification of the baby’s death, his parents are grief-stricken but unknown to them and Astyages as well, as Harpagus gives the child over to his chief shepherd, Mitradates, to dispose of, the will of God is stronger than all. Upon returning home, Mitradates is distressed to learn of the death of his own child and, on a whim, his wife and he substitute the corpse for Cyrus and pass off his death without a hitch. Raised as a shepherd boy until, through unexpected circumstances, he comes to the palace an adolescent, he is ultimately recognized as a possible heir to the throne. With Cyrus back in Persia and Astyages becoming more nervous of his grandson’s power, a force is gathered by Astyages to invade Persia but Harpagus turns loyal to Cyrus based on the king’s cruelty and arranges with Darius, Cyrus’ uncle, that half the army will fight for Cyrus. At the completion of the battle, Cyrus is victorious. Eventually he will become king of both the Persians and Medes.

At this time as well, Jewish discontent is fomenting due to their religious persecution and captivity by the Babylonians, which the reader experiences through a raid on Rabbi Hermon’s house during a weekly meeting, as the Jews impatiently wait for their prophesied coming deliverer. We also encounter Jewish history through the activities of Azariah, better known by his Babylonian name of Abednego from Biblical tradition, and his relationship with a Babylonian woman, Iris. History weaves into story, battles into harmony, and captivity into freedom. It’s an enduring story that Nagel has obviously thoroughly researched with his attention to historical detail and the relationships he so subtly crafts. Themes of loyalty, betrayal, persecution, love, friendship, death and perseverance, one can hardly put it down.

Isaiah 45: 1-3

Thus says the Lord to His anointed,

To Cyrus, whose right hand I have held—

To subdue nations before him

And loose the armor of kings,

To open before him the double doors,

So that the gates will not be shut:

I will go before you

And make the crooked places straight;

I will break in pieces the gates of bronze

And cut the bars of iron.

I will give you the treasures of darkness

And hidden riches of secret places,

That you may know that I, the Lord,

Who call you by your name ……..

⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚⚚

This book contained a number of wonderful quotes of which I’ll share. There are many but every one is worth reading!

Quotes:

“When one is full of himself, he is empty.”

“Love is a very rare quality. So many emotions are mistaken for love. Of all the counterfeits, lust has always been love’s strongest opponent. Nothing is so wonderful, so conducive to happiness, so health-producing, as the heart union of two lives, where true love reigns and lust has no power.”

“If there is one thing heaven hates in man it is pride. Not self-respect, but that quality of pride which causes a man to think more highly of himself than he ought.”

“Unholy ambition has brought ruin to many a man who has followed her unhallowed footsteps. Multitudes of the human family have suffered and died because of the ambition of one. He that loses his conscience has nothing left that is worth keeping.”

“How often we doubt because we cannot know all that is going on which we cannot see. Faith is believing in God. It is taking Him at His word. It is evidence when there is no evidence in sight. It is ‘the substance of things hoped for.’ Belief is accepting a map; faith is taking the journey.”

“Patience is a pearl oft produced by petty irritations. The human heart cannot be whole until it is broken. Care becomes its own cure when it drives us to prayer. To our prayers God gives answers, but in His love, makes ways and times His own. Their leaders wisely taught the people not to worry about the future, but to be optimistic. Nature hates to disappoint the man who is always looking for the worst to happen. We only live a day at a time.”

“The average man is like a match; if he gets lit up, he loses his head.”

“And Astyages talked boastfully on, like a man who may think he is eloquent when he is only evaporating.”

“Those who throw themselves away usually do not like the place where they land.”

“Best character is developed amid storm clouds and tempests.”

“Conscience is not like a bore; if you snub it a few times, after that it won’t bother you.”

“When one was asked the secret of his happy life, he replied: ‘I have a friend.’ True friends are to be cherished for they are precious. One should keep a little cemetery in which to bury the failings of one’s friends. The man who never puts in an honest day’s work on friendship’s railroad, has no reason to expect a sidetrack to his door. Selfish people may have acquaintances but not friends. With some people you invest an evening, with others you spend it.”

“Cyrus was naturally of a very affectionate disposition. He had a great deal of sentiment. No man is worth much without it but to have too much is suicidal.”

“God has not promised to do for us that which we can do for ourselves.”

“Some of the unhappy folk in our world today are men and women with more money than they know what to do with.”

“It has been said that happiness is made of so many pieces that there is always one missing. Happiness is never found by searching for it. Like boys chasing butterflies, happiness is always just out of reach. It does not consist in a fine house, fine furniture, a sixteen-cylinder car or alot of money. In many places dwell unhappy hearts. All of the things enumerated may conduce to happiness but the poor man has access to happiness as well as the rich.

Happiness consists in contentment, in having a clear conscience. It will be found in acting in an unselfish manner towards others. You cannot pour the perfume of happiness upon others without getting a few drops on yourself. Victor Hugo has well written: ‘The supreme happiness of life is the conviction of being loved for yourself, or more correctly, being loved in spite of yourself.'”

Quo Vadis: “It was close to noon before Petronius came awake, feeling as drained and listless and detached as always.”

Quo Vadis: “It was close to noon before Petronius came awake, feeling as drained and listless and detached as always.”