“The family of Dashwood had been long settled in Sussex.”

Mr. Dashwood of Norland Park has passed away leaving his wife, Mrs. Dashwood, and three daughters, Elinor, Marianne, and Margaret to the mercy of their half-brother, John Dashwood, now owner of their ancestral home. While John had promised his father to care for his step-mother and sisters and settle money on them for their comfort, he is quickly and deftly talked out of giving them anything by his mercenary wife. The Dashwood family is left to accept Barton Cottage, a small cottage in Devonshire, offered to them by a distant cousin, Mr. Sir John Middleton. Yet before they leave Norland, Elinor forms an attachment with Edward Ferrars, the brother of her callous sister-in-law, a good-natured young man, who appreciates Elinor’s sense and temperance.

At Barton Cottage, the family meet their benefactor, Sir John, a rather buffoonish cordial man, with a wife with a character as warm as winter. Despite their reduced circumstances, the Dashwoods accept their new life with, more-or-less, a cheerful resignation and begin to move about in society, meeting the dour and grave Colonel Brandon. Brandon is attracted to Marianne, but at thirty-five years old, he seems rather ancient to her, and his disposition does not exemplify all the sensitivity, feeling and passion that she considers essential in a man. During an accident in the rain, Marianne is rescued by a young gentleman, Willoughby, and his nature, in contrast to Brandon’s, appears to be everything her heart desires. His love of books, music and poetry correspond identically to hers; his impulsiveness and his carefree love of pleasure; his immoderate abandon in the face of love. Their marriage soon appears to be a surety, but when Marianne learns of his engagement to another, her heart and all her preconceived ideals are damaged.

Meanwhile, Edward Ferrars pays a visit, yet while Elinor feels an ardent connection between them, Edward appears indecisive. She soon learns of his engagement to a Miss Lucy Steele and, contrary to Marianne’s disposition, she is forced to suppress her natural feeling for the sake of convention, but also self-respect.

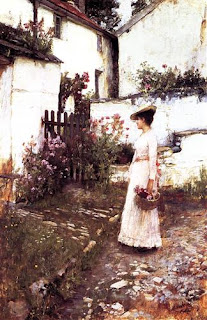

|

| Gathering Flowers in a Devonshire Garden John William Waterhouse source Wikiart |

The juxtaposition of sense and sensibility is played out and embodied in the characters of Elinor and Marianne. Elinor’s sense is soon made apparent. “Elinor, the eldest daughter whose advice was so effectual, possessed a strength of understanding, and coolness of judgement, which qualified her, though only nineteen, to be the counsellor of her mother, and enabled her frequently to counteract, to the advantage of them all, that eagerness of mind in Mrs. Dashwood which must generally have led to impudence. She had an excellent heart; her disposition was affectionate, and her feelings were strong: but she knew how to govern them: it was a knowledge which her mother had yet to learn, and which one of her sisters had resolved never to be taught.”

Marianne, in contrast, is all unbridled sensibility, and shows a contempt for those who are not as passionate. While her sensibility is a sensation of passion induced by positive emotions and experience, such as love, poetry, music, and a response to beauty, it is a wild impulsive, unrestrained, vehement emotion, and Marianne allows herself to be governed by it entirely. As young colt strains against the teaching rein, so Marianne pulls against the constraints that society places on her as a young woman in Georgian England.

|

| London (1808) William Turner source Wikiart |

Yet while Austen shows the differences and consequences of the two character traits, with her usual insights and character crafting she does not put either sister in a tidy box. While Marianne is wild and impulsive, she also show glimmers of sense. As her character develops, Willoughby’s true nature is revealed to her, and through him her own nature is reflected back into her eyes. She recognizes her faults and strives for change. Conversely, it is not that responsible, pragmatic Elinor doesn’t feel; she has similar strength of emotion and attachment as her sister, but her emotions are bridled. Elinor’s sensibility is there, but it does not overpower her sense and therefore allows her to see situations in a clearer light, and from that she is able to govern her life in a way that not only brings respect and contentment to herself, but is beneficial for those people around her.

As usual, Austen gives us a kaleidoscope of characters and while there is strict delineation between the different levels of society, she also shows the colourful interactions that cross those boundaries between them. She juxtaposes two situations, one were engagements are incorrectly assumed for both sisters, and then the turmoil of both sisters when it is known that Willoughby and Edward are engaged to other women. Yet it is the characters that offer us a lesson, as their behaviour determines the outcomes of each situation, and gives us an intimate look at the correct balance of both “sense” and sensibility”.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)