“To be or not to be, that is the question …….”

First publish around 1602 (although a working copy is thought to have been in use in 1601), Hamlet has come down to us in two forms. Issued in 1603, a corrupt or crude and probably pirated copy called the “First Quarto” (Q1) was produced, then in 1604 a more complete and artistically styled “Second Quarto” (Q2) followed. It is supposed that the errors in Q1, complete with pretentious and often meaningless rhetoric, spurred Shakespeare and his company to press for a more complete and credible version. Surprisingly, Hamlet was never performed or printed in its entirety during Shakespeare’s lifetime and the copies we read today are a compilation of Q2 and the 1623 Folio edition. In spite of the errors and incompleteness of the play, there is little doubt that it is Shakespeare’s as it was performed by his own acting company. The evidence of the dating of the play is quite fascinating, as it not only uses clues from registries, but clues imbedded within the play to events that happened in 1601 and 1600. Shakespeare actuates very detailed detective work.

|

| Portrait of Hamlet (c.1864) William Morris Hunt source Wikimedia Commons |

The legend of Hamlet goes back centuries, dating to around the Scandinavian sagas. It was familiar to the people of Iceland in the 10th century, although Shakespeare possibly drew from Histories Tragiques (1559-70) by Francis de Belleforest, relating tragic stories of great kings and queens whose lives had been ravaged by love or ambition. A second hypothesis is that Shakespeare revived an extant version of a play by Thomas Kyd, revising this earlier piece to become the Second Quarto (Q2), and then afterward rewriting the complete acting text and play, which then became the basis for the Folio of 1623. With regard to the first hypothesis, the similarity of the stories are too apparent to be coincidental, but there are differences in names and some differences in narrative that indicate Shakespeare was intent on making the play his own.

Hamlette at The Edge of the Precipice hosted a Hamlet Read-Along beginning in October and set a very leisurely pace, which was wonderful as it allowed me to dig very deeply into the play. My scene-by-scene postings were as follows:

Act I : Scene I, Scene II, Scene III, Scene IV, Scene V

Act II: Scene I, Scene II

Act III: Scene I, Scene II, Scene III, Scene IV

Act IV: Scene I, Scene II, Scene III, Scene IV, Scene V, Scene VI, Scene VII

Act V: Scene I, Scene II

|

| The Young Lord Hamlet (1867) Philip Hermogenes Calderon source Wikimedia Commons |

The play itself begins in Denmark at Elsinore castle where two soldiers see a ghost on the ramparts. It is the ghost of the newly dead King Hamlet and immediately they inform his son, Hamlet, of the apparition. Horatio, his friend, keeps watch with him the following night, whereupon the ghost claims to his son that he has been murdered by his own brother, the new king, Claudius. To add insult to injury, Claudius has married Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, an outrage that can hardly be borne by Hamlet. Yet questions pile upon Hamlet, enough to smother. Was the ghost truly there, and if so, was it really his father? Revenge was called for but how could the deed be done, and was he justified in taking a life? His father’s life was cut short “in the blossoms of his sin”, but if he dispatched Claudius in his guilty state, would not their deaths become parallel?

|

| Hamlet encountering the Ghost (1768-69) Benjamin Wilson source Wikimedia Commons |

The contrary questions paralyze Hamlet into a mire of inaction. He then works out a contrary persona, playing at an odd type of insanity, yet often dispensing insightful, sharp and clear rhetoric to torment Claudius into confusion. Is Hamlet as dangerous as Claudius believes or is he merely an innocent victim of the circumstances, grief-stricken over the death of his father? After Hamlet unwittingly commits the murder of Polonius, the advisor of Claudius, he forces the hand of the new king who sends him to England, with the intent of extinguishing any threat to his kingdom. Yet Hamlet has also injured the mind of one once dearest to him, Ophelia, the daughter of Polonius, and her decent into madness colours the kingdom with further calamity. Upon Hamlet’s return, the culmination of this revenge tragedy is set into motion. Will Claudius’ plotting bring him success? Can Laertes avenge his father, Polonius’, murder, and will Hamlet’s revenge bring him the peace he seems to seek?

You can see throughout the play the emphasis on action vs. inaction, words vs. action, thoughts vs. action, etc. While Hamlet bemoans his inability to act to avenge his father’s death, on the surface seeming cowardly and ineffective, the actuality is quite the opposite. All throughout the play, Hamlet uses thoughts and words to manipulate his enemy. His thoughts, though he bemoans them, actually have more of an effect than he imagines, controlling certain small acts in a very effective manner. His act of insanity twists Claudius into a Gordian knot of uncertainty, his letters announcing his return to Denmark pushing Claudius to drastic action. Thoughts and words appear to be more important and certainly more effective than action, torturing his enemy to the very limits of his endurance. While it’s demonstrated in the play that revenge only brings suffering, is there a underlying theme that words can be more effective than action?

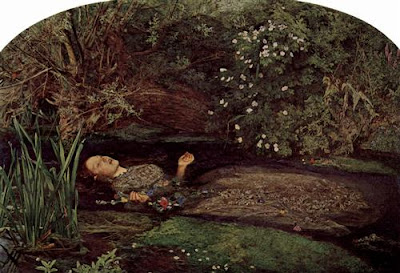

|

| Ophelia (1863) Arthur Hughes source Wikiart |

While the cultural precepts of the Danish society in Hamlet seem to support the desire for revenge, Shakespeare’s Elizabethan audience would have viewed the thirst for vengeance as primitive, and perhaps rather shocking. There is evidence throughout the play that revenge brings only suffering and death to those involved. Fortinbras, the heir of the Danish kingdom at the end of the play, calls for all the noblemen to hear the story of Hamlet:

” Let us haste to hear it,

And call the noblest to the audience ……”

He wants the nobles of the kingdom to attend to this tragedy and learn from it. Horatio responds:

“But let this same be presently performed,

Even while men’s minds are wild, lest more mischance

On plots and errors happen.”

Hamlet does get a hero’s remembrance, but the deaths, suffering and pain caused by his vengeful actions, and those of others, are strongly emphasized.

There is a question throughout the play of Hamlet’s sanity. Is he truly mad, or is it simply an act produced to set a trap for the murderer of his father? I tend to think the latter, but Shakespeare appears to quite closely link insanity with revenge, perhaps alluding to the fact that vengeance has a detrimental effect on our minds, distorting perceptions to bring about a type of madness. Hamlet is playing at being mad, but madness also plays with him, his malevolent sentiments poisoning his very psyche, and modifying his entire moral perspective. The whole character of Hamlet is played out in the agonizing conflict within his mind. Mad he is, and mad he is not, perhaps making him at once to be and not to be.

e