Book VIII (Urania)

“These are the Hellenes who were assigned to the fleet.”

Herodotus catalogues the Hellene ships that fought at Artemision. Seeing the size of the enemy fleets, the Hellenes prepare to desert, but Euboeans bribe Themistokles to remain, who in turn pays off others and the battle begins. The Persians decide to surround the Hellene ships at Artemision by covertly hiding behind islands and approaching from another direction. However, a man named Skyllias of Skione, a lauded diver, decides to desert the Persians and, after jumping from a ship, swims nine miles under water to reach the Hellenes. Herodotus counters this story with his own opinion that Skyllias came by boat . Nevertheless, he reveals the plans of the Persian fleet and the ships that were sunk in the storm. The Hellenes decide to sail out to meet the barbarians and become encircled by the superior force of Xerxes, who thinks them mad. Employing their breakthrough maneuver, the Hellene ships are able to take thirty of Xerxes’ ships and capture a prominent personage, the king of the Salaminians. As night falls, the two sides withdraws, with some desertions of ships over to the Greek side, however the Hellenes decide to retreat and Themistokles attempts to woo the Ionian and Carian forces who are fighting with the Persians, thinking that bringing them to the side of Hellenes will turn the tide of the fighting. He puts a plan into motion to burn Euboean flocks to hide their departure, but a messenger arrives from Thermopylae, relating the fate of the Hellenes there. Deciding it imperative to leave immediately, messages are left for the Ionians and Carians urging their desertion. The Persians investigate the Hellenes’ flight, then Xerxes, up to his old tricks, conceals the Persians losses at Thermopylae by burying most of his dead and leaving only 1,000 on the battlefield (in actuality there were 20,000 killed) whereas the Hellene losses show 4,000 men.

|

The Bank of Thessaly (1926)

Giorgio de Chirico

source Wikiart |

The Thessalians attempted to threaten the Phocians into given them money in exchange for protection from the invading forces, but because of previous resentments between the two, the Phocians refused and that is why the Thessalians gladly guide the barbarians as they advance towards Hellas. The people flee, but the barbarians ensure that they burn and raze every place to the ground. While they continue their rape and plunder, another Persian force is heading towards Delphi to capture its wealth for King Xerxes. When they hear of the advance, all the Delphians leave the city except sixty men and a prophet. And just as the barbarians approach the temple, thunderbolts shoot out of the heavens and two peaks of Parnassus crack off, crushing the forces under their stones. Terrified, the barbarians take flight and the Delphian men pursue them, killing a great number.

When the Greek fleet leave Artemision, they decide to anchor at Salamis after learning the Peloponnesians are not joining them but instead are building a wall to protect Peloponnese and they also want to evacuate their women and children from Athens to obey an oracle. When the Greek fleet at Troizen learns that the others are at Salamis, they set out to join them, making a much bigger fleet than at Artemision and all are commanded by the Spartan, Eurybiades. Here follows a catalogue of ships from the different states and islands. As the generals hold council, Xerxes has been trompsing through Boeotia, Attica and finally reaches Athens. There are a few Athenians left to defend it, but the Persians wrap their arrows in hemp and light them on fire to burn down the barricade. When held at an impasse, the Persians manage to climb the unscalable cliff to the Acropolis and finally capture it, murdering the suppliants, plundering the sanctuary and setting fire to the whole. When the Hellenes learn of the ruin of Athens, they are deeply disturbed and Mnesiphilos advises Themistokles not to let the fleet leave Salamis for fear that they will panic and disperse to their various states to protect themselves. Gathering Eurybiades, Themistokles convenes the generals and convinces them to stay and battle at Salamis.

As Xerxes was successful in his march, others joined him so that his loses were hardly visible. After his victory at Athens, he consults the men on board his ships to see what they advise. All recommend a battle at sea, yet only Artemisia, the woman commander, advises against it. While impressed by her response, Xerxes nevertheless follows the majority and gives the order to set sail for Salamis. Their movement causes terror among the Hellenes, however the Peloponnesians were still completing the wall they had started after learning of Leonidas’ defeat at Thermopylae, and the work continues day and night as a race against time.

As the Hellenes begin to argue again as to the best course of action to take, Themistokles sends his servant, Sikkinos, to Xerxes’ camp to convince the Persians to engage the Greek fleet at Salamis before they flee. He is victorious in his own right and the Persian fleet leaves for Salamis where the Hellene generals are still arguing, unaware that they are being surrounded by the enemy. Meanwhile, Aristeides returns from exile, and Herodotus believes that in spite of his circumstances, that he was “the best and most just of all the Athenians.” Although an enemy of Themistokles, he puts away his enmity and tells him of the encircling of the Persian fleet, whereupon Themistokles asks him to reveal the news to his contemporaries. Doing as he is bid, Aristeides reveals their position, yet he is not believed by the commanders until a Tenian trireme arrives and confirms his story. Thus, the battle begins.

Most of the Ionians fight well for the Persians, in spite of Themistokles’ previous attempt to get them to desert. However, many of Xerxes’ ships are destroyed versus very few Hellene ships because the Hellenes remained in battle formation and fought together whereas the Persian force was disorganized and, more to the point, many of the men did not know how to swim. Whenever a Hellene ship was wrecked, the men simply swam to shore. Artemisia wins acclaim for herself in two very suspect manners: 1) she rams a friendly ship, whether by accident or design Herodotus does not know, and the Attic/Hellene ship pursuing her either thinks she is on their side, or has, deserted to their side, and ceases pursuing her, and; 2) as King Xerxes watches from his station at the base of mount Aigaleos, one of his men commends Artemisia for sinking an “enemy” ship and Xerxes, proud of her feats, remarks, “My men have become women, and my women, men!”

With the great confusion of his fighters, the Phoenicians come to Xerxes and attempt to blame the Ionians for treason, yet as Xerxes observes an Ionian act of bravery, he becomes impatient with the Phoenicians and orders their heads to be cut off so they will learn not to “slander their betters”. In the battle, Persian ships attempt to flee but are pursued by the Aeginetans. The Aeginetans are the premier naval fighters at Salamis, followed by the Athenians. There is a story of the Corinthians fleeing the battle, only to be encountered by a ship sent by some god, the crew of which tell them of a Hellene victory. Finally convinced, they sail back but the battle is over, however this is an Athenian story and the Corinthians tell a story of their courage of which the rest of Hellas is in accord.

Aristeides gathers hoplite soldiers and proceeds to kill all Persians on the island of Psyttaleia. Much wreckage from ships washes ashore, fulfilling many oracles and Xerxes eventually grasps the magnitude of the disaster before him and, worried that the Hellenes will break apart the Hellespont and trap him, he makes plans to return home. To cover his intentions, he begins construction of a causeway to Salamis and also prepares for another battle, fooling everyone but Mardonios who is familiar with the king’s mind. Xerxes sends a messenger home to announce the Persian catastrophe and the Persians appear to be more worried about the safety of their king than his success. Mardonios, reluctant to give up the battle, counsels that Xerxes return home with the majority of forces, but if he leaves him 300,000 troops, he will deliver Hellas to him, enslaved. Xerxes summons Artemisia to consult her and she advises to follow Mardonios’ plan as, if it succeeds, Xerxes will take much of the credit, and if it fails, Mardonios is no great loss. Such is his terror, Xerxes adopts her counsel, trusts her to take his sons to Ephesus and gives Mardonios his men. When the Greeks learn of the flight of the Persian fleet the next morning, they set off in pursuit, stopping on the island of Andros. Themistokles advises that they should sail directly to the Hellespont and destroy the bridges, but Eurybiades goes against his advice, saying that if the Persians are trapped, they will take Hellas little by little. The other commanders agree to leave them a flight path, and Themistokles then advises the Athenians not to pursue the barbarians. His advice is intended to gain favour with the Persians if he ever needs their assistance and he sends his servant, Sikinnos, to relate to them that he has convinced the Athenians to let the Persians leave unmolested and with the Hellespont intact. The manipulator! He then proceeds to besiege Andros for refusing to pay him, and extorts money from other islands without the other commander’s knowledge. Xerxes withdraws and Mardonios with him, deciding it is not the time of year to wage war and is content to wait. The Persian troops suffer starvation and plague and whoever is left is detained at the Hellespont, as the bridge of ships was damaged in a storm. Another story goes that Xerxes went by sea to Asia and the boat was overcome by a storm. The helmsman made men jump into the sea to lighten the load and when they reached land safely, Xerxes gifted him with a crown of gold for saving his life, then decapitated him for the destruction of the lives of the men. Herodotus does not believe this story; if it was true, of course, the rowers would have been thrown overboard, not the notable Persians!

Unable to take Andros, the Hellenes return to Salamis to make offering for their victory. They then sail to the isthmus to present a prize to the two men who showed the most valour in the war. Of course, every man places the first vote for himself, but the majority of the second votes go to Themistokles, however because of jealousy, they will not award him a prize. Themistokles travels to Lacedaemon where they graciously presented him with an olive branch, a fine chariot and a escort of 300 Spartans called “the Knights”, the only time anyone has received such honours.

As the Persian king retreats, some areas revolt, particularly Poteidaia. After Artabazos finishes his escort of Xerxes, he attempts to subdue the Poteidaians but the people hold out against his siege and discover their general’s treasonous activities. When the barbarians try to cross the sea at low tide, a flood tide comes and drowns many of them. Meanwhile, the Persians wait to hear of the success of Mardonios, confident of his victory.

Mardonios decides to consult oracles and sends Mys to find all that he can, and at the Theban oracle, it gives a prophecy in the barbarian tongue instead of Greek to the surprise of all. After reading the oracles, Mardonios sends Alexandros of Macedon (not Alexander the Great), to Athens to try to convince the Athenians to desert to the side of the Persians; Herodotus is unsure if this was because of the prophecy of the oracles or not. He then recounts how the Temenids settled Macedon where Silenos was captured in the garden of Midas (see Metamorphoses – Book XI) And thus, Alexandros arrives in Athens and attempts to convince the Athenians to support the Persians, particularly emphasizing the strength of Xerxes and Mardonios’ troops, whereupon the Lacedaemonians, distressed at the Athenians’ possible betrayal, entreat the Athenians to hold firm and not allow the enslavement of the Hellenes. In a rather elegant speech, the Athenians unequivocally refuse to reach an agreement with Xerxes and chastize the Lacedaemonians for believing that they would ally themselves with such a ruler who has destroyed their city and gods. The urge the Lacedaemonians to prepare for war.

|

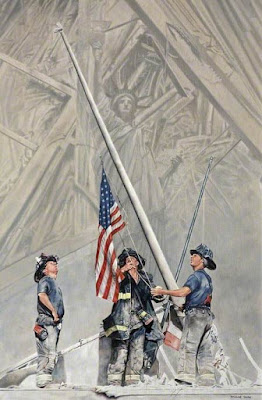

View of the Acropolis (1849)

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

source Wikiart |

⇐ Book VII (Polymnia) Book IX (Calliope) ⇒