Book VII (Polymnia)

“When the report of the battle of Marathon reached Darius, son of Hystapes, who had already been thoroughly exasperated by the Athenians’ attack on Sardis, he now reacted with a much more intense fury and became even more determined to make war on Hellas than he had been before.”

Yes, Darius is irritated, but Darius always seems to be irritated about something. And now the pesky Egyptians have revolted so Darius prepares to wage war against both Egypt and Athens. To top it all off, his sons are now quarrelling to detemine his heir and Darius finally chooses the older son, Xerxes, born to his second wife, as he was the first son born while Darius was king. While amassing troops for war, Darius dies and Xerxes takes over kingship. At first, he does not wish to fight with Athens, but Mardonios convinces him with a variety of different arguments, as well as a number of delegations hostile to Athens influence his decision. However, first Xerxes marches against Egypt, subdues them and imposes even more rigid subjugation on them than his father.

Xerxes then gathers together the noble Persians and states his reasons and expectations for attacking Hellas, backed up by Mardonios. Only Artabanos, son of Hystaspes and uncle to Xerxes, speaks up, stating many reasons for exercising caution before declaring war and then asking that the king remain behind if the Persians indeed march on Hellas. Enraged by his uncle’s request, Xerxes orders him to remain behind with the women for his faithless words; conflict was inevitable and one country or the other would expand its dominion —- let it be Persia! However, later that night, after pondering the discretion of Artabanos, Xerxes realizes that attack would not be prudent. That night a man in a dream visits him, ordering him not to change his mind but nevertheless the next day, Xerxes gathers the nobles and informs them of his reversal of the original plans, for which they are well pleased. Yet that night the dream comes again and threatens him with a short rule if he does not attack Hellas. Completely disconcerted, Xerxes calls for Artabanos, describing his experience and asking his uncle to sit on his throne and sleep in his bed that night then, if the dream visits him too, it should be heeded. Thinking to prove Xerxes’ dream pure nonsense, Artabanos retires to bed but surprisingly has the dream as well and awakes shrieking. Thus, the expedition against Hellas comes to fruition, the largest expedition the Persians had ever mustered. Xerxes builds a canal through the isthmus near to Mount Athos to avoid the previous disaster of the last Persian fleet. Apparently the Phoenicians were the cleverest of the builders, digging the trenches much wider at the top so the dirt did not continually fall on them. Herodotus, however, thinks this display was just to showcase Xerxes’ power, as ships could have easily been dragged across the isthmus.

|

| Xerxes’ Canal source Wikimedia Commons |

On the march, Xerxes comes to Kelainai where the skin of Marsyas is hung (see Metamorphoses Book VI for the story of Marsyas) and meets Pythios who shows hospitality to the Persians and offers them wealth in their quest. His offer metes him land, the title of guest friend, and Xerxes’ goodwill. When the king reaches the Hellespont, he sends messengers to Hellas once again requesting earth and water, as his father had. He then set to work building bridges to cross it but they are destroyed by a storm. Infuriated, he orders the bridge supervisors beheaded and then proceeds to order 300 lashes to the Hellespont, as well as dropping shackles into the sea while spewing insolent imprecations. The new bridge is a pontoon bridge made of boats, of which Herodotus gives detailed description, and after its completion, the army waits for winter to pass. An eclipse occurs which the Magi declare a good omen, but Pythios is disturbed by it and begs Xerxes to release his eldest son from the expedition whereupon, in a rage, Xerxes chops the son in two.

| Xerxes punishes the Hellespont source Wikipedia |

The army marches out, and the troops around the king are elated, then when Xerxes reaches Abydos, he decides to review his entire army so he sits on the marble throne and watches ships race. Suddenly, from his position of contentment, he bursts into tears and his uncle Artabanos, who counselled against the expedition, asks him what is wrong. Xerxes replies:

“…… I was suddenly overcome by pity as I considered the brevity of human life, since not one of all these people here will be alive one hundred years from now.”

They speak of the expedition and Xerxes questions that if Artabanos’ dream vision was different, would his counsel still have been the same? Artabanos explains that he is fearful of his two great enemies, the land and the sea, both of which are formidable. Xerxes counters that it is better to act with fear than to fear everything and not act at all. Finally the army crosses the Hellespont and Xerxes ignores two portents depicting his expedition’s failure, as they march towards Hellas. His land army numbered 1,700,000 men, including Persians, Medes, Kissians, Hyrcanians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Egyptians, Baktrians, Scythians, Indians, Areians, Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians, Gandarians, Dadikais, Caspians, Sarangians, Paktyes, Outians, Mykians, Parikanians, Arabians, Ethiopians, Libyans, Paphlagonians, Ligyeans, Matienians, Mariandynians, Syrians, Phrygians, Armenians, Lydians, Thracians, Meionian Kabales, Cilicians, Moschians, Tibarenoi, Makrones, Mossynoikians, Mares, Colchians, Alarodians, Saspeires, and island peoples from the Erythraean Sea. A long list but worthwhile I think to even begin to imagine the numbers on the march. The commanders and generals are listed. Thus follows descriptions of each contingent’s dress and means of transport, then Herodotus moves on to recount the fleets of each including a woman commander named Artemisia who was part Halicarnassian and part Cretan.

|

| Crossing the Hellespont source Wikipedia |

Xerxes now surveys and categorizes his troops, then asks of the exiled Spartan king, Demaratos, if the Hellenes would dare to fight against such forces. Demaratos speaks only for the Lacedaemonians that if confronted, they would fight to the last man. Xerxes, however, laughs at such a foolish claim, and declares that if they were ruled by one man, he could force them to comply but given their freedom, they would not. Demaratos insists that they are compelled by a law forbidding them to flee from battle. Nevertheless, Xerxes chuckles at his delusion and sends him away.

Xerxes’ route towards Hellas is now described, along with leaders he praises for their support, but more startling is the impact such an enormously amassed expedition has upon the cities and towns through which it passes. Rivers and lakes are drained dry by the sheer numbers of men and their beasts of burden. Camels are attacked by lions, en route, yet no other man or animal is touched, and Herodotus is puzzled by this odd occurrence. In Thessaly, Xerxes is interested in the course of the river Peneios which is surrounded by mountains, and he is content with the area’s subjection to him as Thessaly would have been easy to take simply by the damning of this river. He decides not to send heralds to Athens and Sparta asking for earth and water, as the last heralds of his father were thrown into a pit and a well, respectively.

|

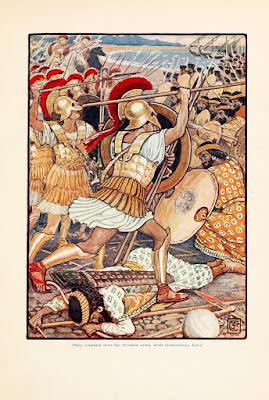

| They crashed into the Persian army …. Walter Crane source Wikiart |

As Xerxes advanced, many Hellenes who had sent earth and water were confident that they would be passed by, but the ones who had refused were rather terrified. However, the Athenians, rather than desert their land or submit to Xerxes, instead remained to fight and this was the saving of all Hellas, or so says Herodotus although he admits his opinion may not be the popular one.

“… they repelled the King with the help of the gods. Indeed, not even the frightening oracles they received from Delphi threw them into a panic or persuaded them to abandon Hellas. Instead, they stood fast and had the courage to confront the invader of their land.”

Themistokles, a prominent Athenian, interprets a second oracle differently than the oracle experts, counselling that they need to use their ships to fight the Persians. Fortunately, these ships had already been constructed for a war with the Aeginetans. Hellas attempts to unite with Argos, Sicily and Crete, while they send spies to Sardis to find out the strength of the Persian army. The spies are caught and taken to be executed but Xerxes intervenes, allowing them to see the magnitude of his force before sending them home again, hoping that the Athenians would thus surrender to his might. The Argives, however, give trouble and when they are not given half command alongside the Spartans, refuse to participate, yet Herodotus says that their lack of participation was prompted by a visit from the Persians who cited ties of kinship to gain their allegiance. More bickering ignites between the Spartan and Athenian envoys and Gelon of Syracuse (Sicily). Gelon wants full command because of the refusal of the two to come to his aid previously, but at the protest of the Lacedaemonians finally agrees to accept half the command, however the Athenians fully refuse to be led at all by him. He sends them away, then dispatches a messenger, Kadmos, to the Persians after they cross the Hellespont, instructing him to offer money, earth and water to them if they win, but to return home if they lose and Kadmos eventually proves himself an honest messenger. The Corcyrians agreed to help but then hang back during the battle like cowards, waiting to see which side will prevail. The Cretans will not help and the Thessalians are more concerned with saving themselves and eventually mediate with the Persians.

|

| Mountains of Thermopylae (1872) Edward Lear source ArtUK |

The forces of the Athenian alliance prepares to defend the territory, but move from the Pass of Tempe to Thermopylae, where they believe the Persian force will land. Herodotus calculates the Hellene forces at around 2,641,610 men, not including slaves, women and concubines, and the Persian forces at 5,283,220. The Persians beach some ships at Magnesia but those which have to anchor in the bay are destroyed by a fierce storm, 400 ships in total, the god Boreas helping the Athenians. On the fourth day the storm ends and the barbarians set sail. Fifteen ships that set sail later than the others end up sailing into a Greek fleet thinking that they are their own and are captured. Events are not transpiring well for the Persians. Meanwhile Xerxes marches with the land troops and arrives near Thermopylae where the Greeks guard the pass. Of the generals commanding the Hellenes, the most prominent is Leonidas, king of Sparta, who became king after his two elder brothers died. When Xerxes sends out a scout, he spies a group of Lacedaemonians combing their hair and, astonished, returns to Xerxes to report his findings. The Persian king calls Demaratos who confirms what he had previously told him, that the Spartans would fight despite smaller numbers and that in grooming themselves, they are preparing for battle. Xerxes, however, remains unconvinced and after four days of assuming the Hellenes would retreat against his forces, loses his temper and attacks. The Medes engage the Hellenes first and are forced to retreat, then the Persians take their place, yet face the same result and again the next day. The Spartans are far superior fighters and lose few men. A Hellene named Ephialtres commits a treacherous act, leading the Persians along an unknown mountainous pass which allows the Persian force to destroy the Hellene fighters. Another account says it was Onetes and Korydallos who perpetrated the treachery, but Herodotus finds this account entirely implausible, given Ephialtres is later exiled and a price is put upon his head. When the Persians reach the summit, they encounter Phocians defenders who flee at the first hail of arrows, leaving the path clear. Finding out about the ambush, some Hellenes desert and some remain to fight.

“It is also said, however, that Leonidas himself sent most of them away as he was worried that all of them might otherwise be killed. But he felt that for himself and the Spartans with him, it would not be decent to leave the post that they had originally come to guard. I myself am most inclined to this opinion and think that when Leonidas perceived the allies’ lack of zeal and their reluctance to share with him in the danger ahead, he ordered them to leave. He perceived that it would be ignoble for him to leave the pass, and that if he were to remain, he would secure lasting glory and assure that the prosperity of Sparta would not be obliterated.”

The Thespians and the Thracians stay behind with the Lacedaemonians, the former because they are willing to remain, but the latter are compelled by the Spartan king against their will for their previous treachery.

|

| Leonidas at Thermopylae (1814) Jacques-Louis David source Wikiart |

Xerxes waits for the peak hour to attack and then the slaughter is dreadful although many Persians are killed as well, including two brothers of Xerxes. Xerxes calls to him Demaratos to ask how many Spartans are left in Sparta and if they are as brave as the men fighting now. The traitor advises the king to capture an island off Sparta as their base to frighten the Lacedaemonians, but the king’s brother, Achaimenes, counters his advice and Xerxes listens. As Leonidas is now dead and his body recovered by the Persians, Xerxes orders him beheaded and his head raised on a spike.

Going back in time, Herodotus explains how Demaratos was able to get a message to the Spartans of the coming Persian invasion, by inscribing a message on the wood of a writing tablet, then putting wax over it so it would appear blank. When it arrived in Lacedaemon, at first they could not understanding the meaning of the blank tablet until Gorgo, the daughter of Kleomenes had them scrape off the wax. A message of warning was then sent to the rest of the Hellenes.