“The clock on the Bourse had just struck eleven when Saccard walked into Champeaux’s, into the white and gold dining-room, with its two tall windows looking out over the square.”

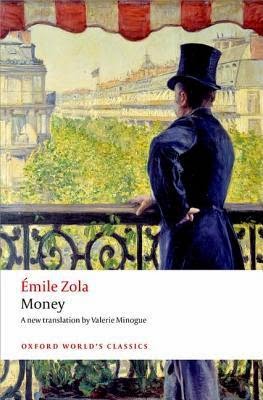

Aristide Saccard is on the move again. Brought low by ruinous business practices (see La Curée or The Kill), his wife dead, and his estate sold, Saccard winds calculatingly through Paris like a snake looking for an opportunity to strike. At first, he is certain that his brother, the government minister, Eugène Rougon, will come to his assistance, but when he hears that his sibling wishes to remove him from Paris for fear of embarrassment, Saccard makes a precipitative move, declaring he will open a bank that will be the financial success of Paris, a venture in which everyone will be clamouring to be involved. His passion and sheer energy sweeps people along with him, including Lady Caroline and her brother, Hamelin, honest and respectable souls, who admire Saccard’s genius. Yet in the world of big money and La Bourse (the French equivalent to Wall Street), allegiances can fluctuate, affiliations change, and behind every corner is the face of your own demise.

|

| Celebration in the Streets of Paris (Montemarte) (1863) Vasily Perov source Wikiart |

“The Bourse is a real forest, a forest on a dark night, in which people can only grope their way along. In all that darkness, if you’re foolish enough to take heed of everything, however inept and contradictory, that you’re told, then you’re sure to break your neck.”

Zola paints an excellent representative portrait of Paris’ frantic and unscrupulous financial world of 1863-during the reign of Napoleon II of the Second Empire. We see how alliances and loyalties are formed only on the basis of financial gain, yet human concern or family loyalties have little value.

“In these covert and cowardly financial battles, in which the weak are quietly disembowelled, there are no more bonds of any sort, no kinship, no friendship, only the atrocious law of the strong, those who eat so as not to be eaten.”

|

| La Bourse (1900) source Wikimedia Commons |

Zola demonstrates through his narrative and his colourful characters, how the lust for money, greed and power are not merely promoted, but in fact, worshiped.

“His wife was never seen, being unwell, said the Marquis, and kept to her apartment by infirmity. However, the house and furniture were hers, and he merely lodged there in a furnished apartment, owning only his personal effects, in a trunk he could have carried away in a cab; they had been legally separated ever since he started living on speculation. There had been two catastrophes already, in which he had blankly refused to pay what he owed and the official receiver, having taken stock of the situation, had not even bothered to send him an official document. The slate was simply wiped clean. As long as he won, he pocketed the money. Then, when he lost, he didn’t pay: everyone knew it and everyone was resigned to it. He had an illustrious name, he made an excellent ornament for boards of directors; so new companies, looking for golden mastheads, fought over him: he was never unemployed.”

As Saccard cleverly constructs his colossal financial empire, he is captivated by money but he is captivated by power more. The thrill of financial battle is as addicting as as drug, and he is high on the power and the ultimate campaigns fought to gain it. It is a house of cards and each trade, each purchase, each decision, is perhaps the one that will cause its downfall.

“Wealth for him had always taken the form of that dazzle of new coins, raining down through the sunshine like a spring shower and falling like hail on the ground, covering it with heaps of gold that you stirred with a shovel just to see their brightness and hear their music ……… But he had always been a man of imagination, seeing things on too grand a scale, transforming his shady and risky deals into epic poems; and this time, with this really colossal and prosperous enterprise, he had moved into extravagant dreams of conquest, with an idea so mad, so huge, that he did not even formulate it clearly to himself.”

|

| Panorama of Paris, 1865 Charles Soulier source Wikimedia Commons |

Also explored are the feelings on anti-Semitism prevalent during the time. Jews were often seen as good for loans but with little else to their character or worth to recommend them. In a world were humanity is held in so little regard, this racism is another head on the monster of greed, power and manipulation.

With his usual descriptive flair and creative technique, Zola allows the reader to skim along the surface of the narrative, to first get your bearings, before he draws you into the story and you are held captive by the machinations of the characters, the vivid depictions of Paris and the power of that elusive yet ever-coveted currency, money.

This book was not Zola’s favourite to write. “It’s very difficult to write a novel about money. It’s cold, icy, lacking in interest ……” Zola said in an interview, but he declined to demonize it, instead choosing to show the effects of its worship in a work that would “praise and exalt it’s generous and fecund power, it’s expansive force.” His technique certainly worked, as the reader becomes the observer of an inanimate object that effectively controls the lives of an empire.