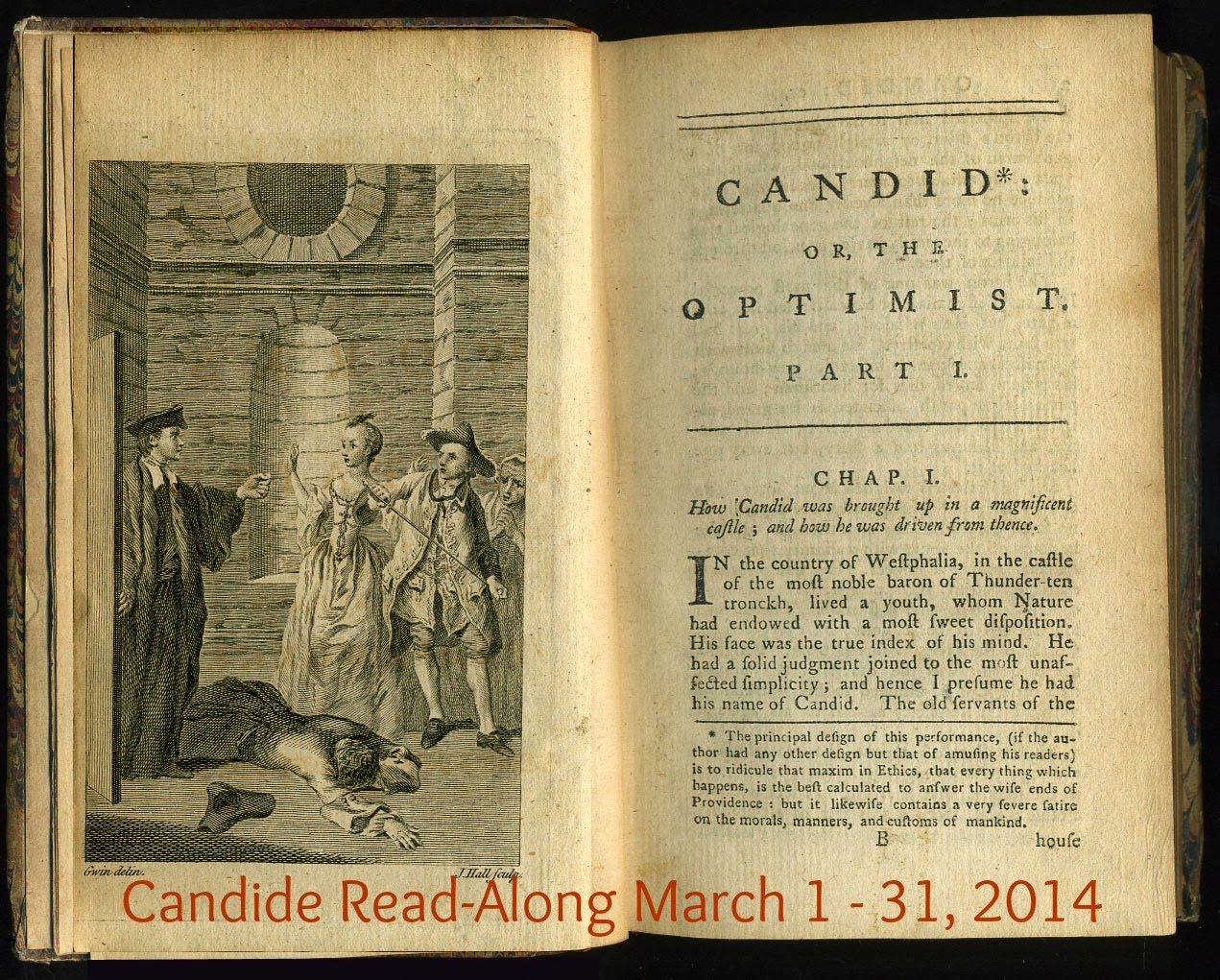

And so begins our Candide Read-Along, hosted by Fariba at Exploring Classics. I was slightly intimidated by this novel but, after doing some research, I feel much more confident that I’ll be able to understand the main points of the novel. That said, this novel, because of it’s satirical nature and specific satirical targets, deserves an introduction.

Introduction

Published when Voltaire was 66 years old, Candide was expressly written to satirize the philosophy of Optimism. This optimism was not simply the positive hope of better circumstances, but the belief that everything that happened was for the best, no matter if good or bad, happy or tragic. This philosophy disgusted Voltaire because he felt that it left no facility for bettering oneself or one’s surroundings and that it supported fatalism and complacency. The tragic earthquake in Lisbon in 1755 seemed to precipitated the writing of this novel, causing the author to question justice in such a calamity, and reflected in his poem, “Poem on the Disaster of Lisbon,” written weeks afterward. Candide was further emphasis of Voltaire’s rejection of the attitude that life was the “best of all possible worlds” and that everything that happened in it was for the best.

Voltaire was an established writer and thinker by the time he wrote Candide, yet a controversial figure who by many was both admired and hated. He was continuously clashing with the government and the church, suffering two periods of incarceration, and most of his adult life was spent exiled from Paris, the city of his birth. Much of his works were published under a pseudonym to avoid prosecution. During a stint in exile, he spent three years in Great Britain and, impressed with the freedoms of England, particularly that of speech, his stay intensified his desire for reforms in his home country. In 1758 he settled in Ferney in eastern France, spending his time farming, writing and supporting local business. Candide was written here, not long after his move.

Satire: the use of humour, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and other topical issues

Chapter 1

Candide, a young man with “sound judgement and great simplicity of mind,” lives in the household of the Baron Thunder-ten-tronckh. It is suspected that he is a child of the baron’s sister and a neighbourhood nobleman. With a innocent susceptibility, he accepts his tutor, Pangloss’ teaching of “everything is necessarily for the best purposes.” Cunegonde, the baron’s daughter espies Pangloss dallying with a maid, decides she wants to repeat the experiment with Candide, but they are caught in the act of caressing by the baron and Candide is literally booted from the house.

Voltaire’s sarcasm is apparent in his treatment of the baron. He gives his castle a pretentious name, makes the baron important merely because he has a castle with doors and windows and praises the baroness for her prodigious weight, equating it with esteem.

Chapter 2

Arriving in the nearest town, Candide meets two Bulgar soldiers who force him to come with him but due to Candide’s naiveté he innocently does their bidding. After being conscripted into the army, he is trained, yet one day when out for a walk he is seized, taken back to the barracks and put on trial. The sentence passed is that he can be beaten by the regiment 36 times (running the gauntlet) or have 12 bullets put into his brain. He chooses the former but, after 3 times is near death. Fortunately the king of the Bulgars happens along and pardons him, realizing that he is “a young metaphysician, utterly ignorant of worldly matters.” The armies of the Bulgars and the Avars then clash in battle.

Voltaire explores army conscription; people were often tricked into serving and severely punished if they did not obey the rules. He also brings in the question of free will: “It did him no good to maintain that man’s will is free and that he wanted neither; he had to make a choice.” I’m not quite certain his point in this; did he deny free will and feel that fate controlled circumstances or did he accept free will but feel that it was limited by our circumstances?

Chapter 3

The two armies meet and there are 30,000 deaths from cannons, rifle-fire and bayonets. Candide decides to go away to reason about cause and effect. He encounters a burned Avar village, with scenes of carnage and molestation, and littered with body parts. In a Bulgar village he finds similar atrocities and decides to go to Holland where he would find Christians who would treat him as he was accustomed to be treated in the baron’s castle. Yet when he begs for alms he is mocked and derided. An orator who is speaking of love labels him a wretch and rejects him outright because he will not speak against the pope. Fortunately he meets Jacques, an unbaptized Anabaptist who gives him shelter, a bath, food, money and offers to teach him to manufacture Persian fabrics. Candide assume this treatment confirms the “all is best in the world” theory. On his walk the next day, he happens upon a diseased beggar.

Voltaire feelings of revulsion of the effects of war is apparent in this chapter. He uses oxymorons to get across the absurdity of war: “….. a harmony whose equal was never heard in hell,” and ” ….. during the heroic carnage,” as well as horrific scenes of slaughter. The hypocrisy of Christianity is also brought to the forefront, which is countered by Jacques, the Anabaptist.

Chapter 4

Candide discovers that the beggar is his old tutor, Pangloss, who gives him the horrific news of Cungonde’s death. Candide faints and when he recovers, Pangloss tells him that the baron and his wife and son were killed, Cungonde was raped and disembowelled and the castle razed to the ground. He blames his affliction on the baroness’ maid who infected him with syphilis, tracing the disease back to Columbus’ shipmate. Jacques pays to have Pangloss cured, the tutor only losing an ear and an eye. Two months later they must travel to Lisbon, and on the ship, Pangloss states it is all for the best but Jacques contradicts him, saying that men are not born bad but make choices that have direct bearing on their situations. Pangloss counters that individual misfortunes are for the greater good. They encounter a raging storm.

Pangloss’ reasoning with regard to him contracting the pox had some sort of weird psychological reasoning which I could not follow. Pangloss rejects that his situation could be punishment for sin or caused by evil. I did like how Jacques mentioned that,

“Men must have a corrupted nature a little, because they weren’t born wolves, yet they’ve become wolves: God didn’t give them twenty-four-pounders or bayonets, but they’ve made themselves bayonets and cannons with which to destroy each other.”

Another comment on the senselessness of war.

Chapter 5

The storm becomes perilous and Jacques is tossed into the sea (after saving a sailor who now does not attempt to save him) where he drowns. Candide wants to jump in to save him but Pangloss prevents this heroic act, explaining the harbour was designed especially for the Anabaptist to drown in. When they reach land, there is an earthquake and later, after getting dinner from some inhabitants that they assisted, an officer of the Inquisition argues with Pangloss that if all is for the best, there then can be no original sin or punishment. Pangloss argues back and they discuss free will. The officer ominously nods to his attendant.

Another instance of free will being mentioned and more of Pangloss’ philosophy. The problem of evil is touched on. Is man evil? Are things like Pangloss’ recent condition and the earthquake punishment for evil? What is purposeful and what is destiny? What can be altered and what is fate? The earthquake mentioned here is based on the real earthquake of 1755 in Lisbon.

Chapter 6

After the earthquake, the “wise men of the country” decided to have an auto-de-fe (or a ritual of public penance, during the first part of which accused heretics were sentenced by the Inquisition), and they burn people to prevent another quake. Pangloss and Candide are arrested, the former for having spoken and the latter for listening. Candide and Pangloss are forced to wear miters, Candide’s with flames pointing down and devils with no claws or tails and Pangloss’ with the flames pointing upward and devils with claws and tails. Candide was beaten to beautiful music, Pangloss was hanged and the earth trembled again. Candide begins to question the “best of worlds,” thinking of the fate of Pangloss, Jacques and Cunegonde. An old woman tells him to follow her.

Superstition seems to be a main theme of this chapter, exemplified by the auto-de-fe in hopes of avoiding another earthquake. Along with Pangloss, two men who would not eat the pork were hanged, obviously two Jews. Candide begins to question the “all is best” philosophy and he no longer has Pangloss to continually reinforce these views. What will happen to his perceptions without his friend?

Chapter 7

The woman takes him to a hovel, feeds him and he sleeps. The next evening she takes him to an isolated house where he finds Cunegonde. He is ecstatic, falling at her feet. Cunegonde tells him Pangloss’ report was true but she survived and will tell him more after he relates what has happened to him since he left the castle. He does.

There is not much to say, except to note the air of mystery in the chapter. It says Candide regards “his whole life as a nightmare, and the present moment a delightful vision.” A flair for the dramatic. Why would he regard is whole life a nightmare when he was completely happy up until the point he was evicted from the castle? I suppose it’s a devise to emphasize his overwhelming happiness at discovering Cunegonde alive.

Chapter 8

Cunegonde recounts the horrors she experienced at the hands of the Bulgars. The Bulgar captain sold her to a Jew and later, when she was noticed by the Grand Inquisitor they decided to share her, although she so far has resisted them both, as “a lady of honour may be raped once, but it strengthens her virtue.” She saw both Pangloss and Candide at the auto-de-fe and suddenly realized that Pangloss’ theory of “all is for the best” is not true. She gave her servant orders to find him and voilà! But Don Issachar, the Jew has arrived home expecting his rights.

Discussion Questions

1) Do you think Pangloss is a predatory figure or merely naive like Candide? In other words, is Pangloss deliberately trying to lead others astray or does he actually believe in the philosophy of optimism?

I think Pangloss truly believed in his philosophy. Voltaire makes him almost blind to what is around him and his comments do not stem from what he actually sees (outward) but solely from what he believes (inward).

2) How do you feel about Voltaire’s writing style? Do you find this book funny or disturbing?

So far I am keeping an open mind. I have not consciously read a book as satire before, so I’m wondering if all satires are as overdone as this one is feeling. I’m finding it mostly disturbing, yet it is so contrived and theatrical, I’m honestly having trouble taking it seriously to have a feeling either way.

3) Who is your favorite character thus far?

Jacques is definitely my favourite character so far. Actually, he is the only character who has seemed like a character; the rest have been more like caricatures.

.jpg)

-ulema.png)