Book II (Euterpe)

“When Cyrus died, the kingship was inherited by Cambyses.”

Upon the death of Cyrus, his son Cambyses took power and immediately led an expedition to Egypt, including the conquered Ionians whom he saw as slaves. Herodotus now falls into a long narrative about Egypt’s land and customs.

|

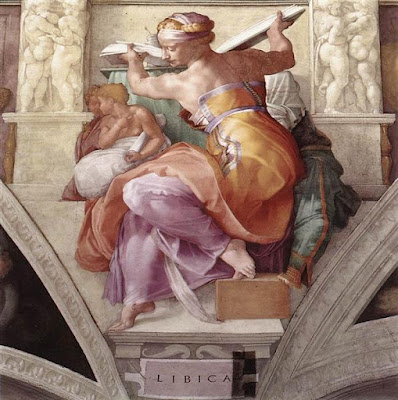

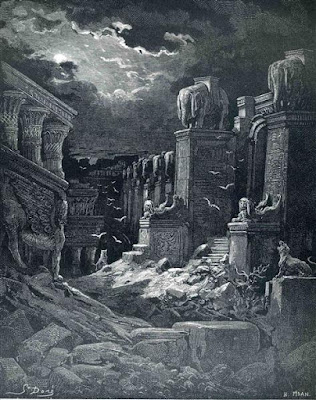

Architecture and Art of the great Temple of Karnak

David Roberts

source Wikiart |

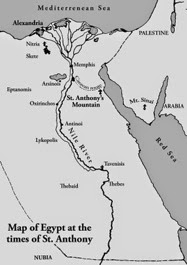

He claims the Phrygians are the oldest people, citing an experiment done with babies to see what the first word uttered would be, however the Egyptians were the first to discover the year by dividing it into twelve parts and adopt names for the twelve gods. Here begins a lengthy description of the land and terrain, the soil and the flooding of the Nile and its channels. Herodotus claims the Hellenes have three theories about the Nile’s floods: 1) the Etesian winds cause the flooding, which Herodotus says is ridiculous; 2) the Nile flows from the Ocean and the Ocean surrounds the entire world, which Herodotus states is even more ludicrous, and; 3) the floods are caused by melting snow from Libya which pass through Ethiopia. The last is the most believable explanation, yet the most erroneous. Herodotus presents his own theory which has to do with the sun being pushed off course by storms, then in spite of Herodotus’ promise to be brief, he offers a rather complex explanation.

|

The Nile (1881)

Vasily Polenov

source Wikiart |

Next, Herodotus launches into a description of Egyptian customs, claiming they are opposite to the customs of other peoples. Here are a few for your enjoyment:

- The women go to the market to sell goods, whereas the men stay home and do the weaving.

- The men carry loads on their heads and the women on their shoulders.

- Women urinate standing up; men sitting down.

- They ease themselves (urinate & defacate, I believe he means) inside their houses but eat outside on the streets.

- Sons do not have to support their parents, but women do.

- Women cannot be priestesses, only men can be priests

- They live together with their animals

- They knead dough with their feet but lift up dung with their hands

….. and so on and so forth.

The Egyptians are pious and Herodotus explains in detail animal sacrifices, then moves on to their understanding of Herakles, which is very different from the understanding of the Hellenes. In fact, Herodotus proves his dedication for discovering the truth by visiting Tyre in Phoenicia to discover how these people viewed the god, as well as a sojourn in Thaos. Herodotus finally concludes that the Hellenes myths of Herakles are the most foolish.

|

The Sanctuary of Hercules (1884)

Arnold Böcklin

source Wikiart |

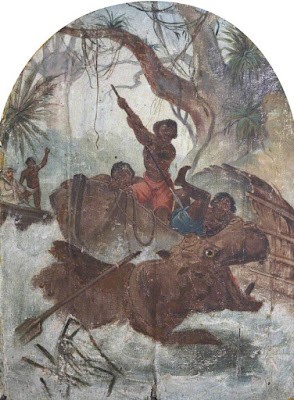

A discussion about where the Hellenes derived the names for their gods follows, and Herodotus is certain most of the names came from barbarians, namely the Egyptians, although Poseidon seems to be borrowed from the Libyans. As to their origin, Herodotus believes that Hesiod and Homer, who lived no more than 400 years before him (modern scholars believe 200 years before), composed the theogony of the gods along with bestowing them with their attributes, behaviours, skills and descriptions. From there we move to religious rituals and festivals, and the Egyptians care of their animals. Do not intentionally kill an animal or you are sentenced to death. For the death of a cat, the household will shave its eyebrows, but for the death of a dog they shave their whole body and head. Many animals get buried in sacred places or tombs. The crocodile is sacred in some places as is the hippopotamus, and my favourite animal, the otter. Herodotus’s description of the hippopotamus is rather implausible:

” …. it has four feet with cloven hooves like an ox, a blunt snout, a mane like a horse, conspicuous tusks, and a horse’s tail. It neighs. It is the size of the largest ox, and its hide is so thick that once it is dried, spear shafts are crafted from it …”

There is a very impolitic footnote stating that obviously Herodotus has never seen a hippopotamus, but honestly who really knows? I choose to believe him, or at least that he thought he saw one, as later he describes a phoenix but is very careful to reveal that he has never actually seen one. From this evidence we can conclude that, at the very least, Herodotus is attempting to be accurate and transparent. In any case, this phoenix carries the body of its father wrapped in an egg of myrrh from Arabia to the sanctuary of Helios when he dies, or so the legend goes.

|

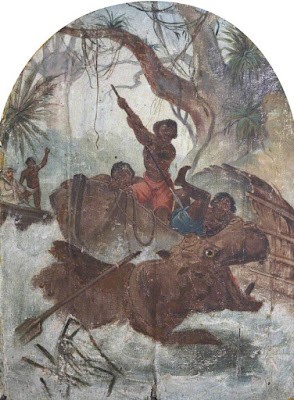

Hatwell’s Gallopers’: Hippopotamus Hunt

Henry Whiting

source ArtUK |

After, Herodotus discusses various themes such as fish, methods of embalming, Egyptian boats, and then begins to share some Egyptian history. Priests told him that the first Egyptian king was named Min who founded the city of Memphis and dammed the Nile. After him, 330 kings followed which included one Ethiopian and one woman (Nitokris – different than the Babylonian Nitokris of Book I) who avenged her brother by locking his numerous murderers in a chamber and drowning them before throwing herself into a chamber of ashes to escape retribution. However, the Egyptians claim these kings were more or less useless except for the last, Moeris (king Amenemhet), who produced a memorial to himself and excavated a lake. King Sesostris, who came after, marched all over Asia erecting pillars to commemorate his victories and would put on them the genitals of a woman for those whom he thought cowardly. When his brother plotted his murder, Sesostris used two of his six children as a bridge to cross a flaming pyre, burning them up, and in this way, escaped with the rest of his family. His son, Pheros, ruled Egypt after him and then came Proteus, with whom Helen and Paris stayed. Herodotus calls into question Homer’s account of the Trojan War stating in his opinion that Helen was in Egypt the whole time of the war. After all:

” … considering that if Helen had been in Troy, the Trojans would certainly have returned her to the Hellenes, whether Alexandros (Paris) concurred or not. For neither Priam nor his kin could have been so demented that they would have willingly endangered their own persons, their children, and their city just so that Alexandros could have Helen.”

|

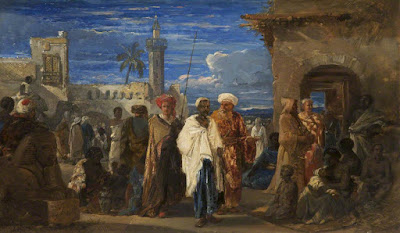

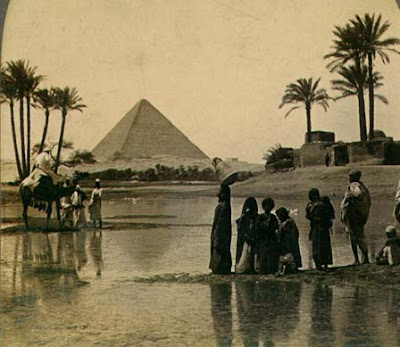

Thebes Colosseums, Memnon and Sesostris (1856)

Jean-Leon Gerome

source Wikiart |

After Proteus, Rhampsinitos assumed kingship, amassing great amounts of silver for which he built a great vault. But the builder made a secret entrance which he told to his sons upon his death and they began to borrow from the king. The king discovered the theft and laid traps for the robbers whereupon one of them was caught, but he convinced his brother to behead him so their identity would not be discovered. The king then took the headless body and hung it as bait but, upon the urging of his mother, the thief made the guards drunk and stole it. The king then set his daughter up as bait in a brothel to attempt to identify the robber (Herodotus expresses his disbelief at the veractiy of this account), but although the thief confessed his sin while enjoying the daughter’s favours, he offered the arm of a corpse he had brought along with him when she tried to grab him, and once more eluded capture. So impressed, the king pardoned the man and gave him his daughter in marriage, then King Rhampsinitos descended to Hades to play dice with Demeter. (Yes, seriously!)

While Egypt prospered under Rhampsinitos, the next king, Cheops (Khufu), laid the people under bondage, forcing the people to do labour for him, hauling stones to build causeways and his great pyramid. His brother, Chephren (Kafre), was not much better and built his pyramid of coloured Ethiopian stone, however, his son, Mykerinos (Menkaure), disliked his father’s policies and enacted change. He is liked more than any other king but at times his leniency caused him great trouble. After sexually abusing his daughter who killed herself, an oracle told him that he only had 6 years left to live, therefore he stayed awake twice as long and extended his life to 12 years. Asychis followed, who built his pyramid of bricks, then a blind king, Anysis, who fled the Ethiopian king who took over, who then fled himself after a dream, whereupon Anysis returned. The Egyptians believe that before the kings, the gods ruled over Egypt.

After Ethiopian rule, they divided the kingdom into twelve districts and kings ruled each, forming alliances but promising not to depose each other. To commemorate them all, they had a marvellous labyrinth constructed that Herodotus claims eclipses the pyramids themselves and he would know as he was shown the upper chambers although denied the lower ones. Yet even with their pact for peace, a mistake brought about dissent. While meeting together, only 11 golden cups were brought out for libation and Psammetichos had to use his helmet. A horrified hush came over the rest of the kings as they realized the oracles proclamation was coming true: that the one who drank from a bronze vessel would reign over all the kingdoms. They decided to exile instead of kill him but Psammetichos returned and with the help of the Ionians and Carians, became sole ruler of the kingdoms. Nechos, the son of Psammetichos, reigned after, constructing a canal and leading military campaigns, before his son, Psammis took over, followed by his son, Apries. Due to a failed military campaign, the people blamed his poor leadership and Apries had to send an envoy, Amasis, to quiet them, however they crowned Amasis king, so Apries sent Patarbemis to fetch his disloyal envoy. Amasis (Ahmose II) refused to return, but Patarbemis was able to determine his intent to attack the king. However, upon return, Apries was so furious that Patarbemis had returned empty-handed, he seized him to cut off his ears and nose before the man could relate his discovery. Amasis with his foreign army of the Ionians and Carians who had settled in the land, met Apries’ Egyptian army in battle and Apries was eventually captured. Amasis treated him well, however, yet the citizens complained and Amasis turned him over to them at their request, whereupon they strangled and buried him.

The people at first despised Amasis because he was merely a common man, but Amasis won them over. Yet he was not a serious man and enjoyed drinking with his friends. Concerned about his reputation, his close friends and family admonished him but Amasis answered:

“When archers need to use their bows, they string them tightly, but when they have finished using them, they relax them. For if a bow remained tightly strung all the time, it would snap and be of no use when someone needed it. The same principle applies to the daily routine of a human being: if someone wants to work seriously all the time and not let himself ease off for his share of play, he will go insane without even knowing it, or at the least suffer a stroke. And it is because I recognize this maxim that I allot a share of my time to each aspect of life.”

Egypt prospered under Amasis and he was also friendly to the Hellenes.