The Journal of William Sturgis: “1799 – On the 13th of February at 7 in the morning we saw the land ahead bearing about N East distant 2 leagues, which we soon found to be the high land about Port Banks, and a Cape to the Southward and Eastward of us distant 3 leagues, to be Cape Muzon.”

In 1798, William Sturgis found a berth on the Eliza, a ship set to leave Boston harbour in the summer on a voyage to the Pacific Northwest to trade in the lucrative business of animal pelts. Sturgis had finished schooling at fourteen, afterwards being employed as a junior clerk in a trading office. With the unexpected demise of his father, Sturgis, knowing that he had to support a mother and sisters, decided to turn to the sea to make his fortune. He was only 17 years old.

|

| Fur traders in Canada 1777 source Wikipedia |

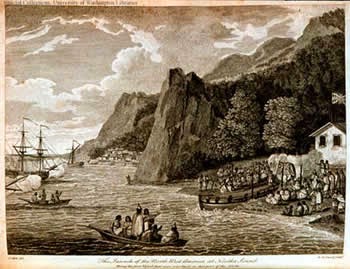

Because Sturgis had had experience in business, the captain of the Eliza asked him to be his assistant, and his quick adeptness at learning the native languages soon saw his rise in stature. The Americans generally coped well with the Indians while trading, and there were few altercations, but the precautions on board ship to assure safety were stringent and followed closely. Because of these safeguards, relations between the two were relatively harmonious and as Sturgis noted years later:

“I believe I am the only man living who has a personal knowledge of those early transactions and I can show that in each and every case where a vessel was attacked or a crew killed by them, [the Indians of the region] it was in direct retaliation for some life taken or for some gross outrage committed against that tribe. This is the Indian law, which requires one life for another, as inflexibly as we civilized nations exact the life of a murderer. The Indian did not forget, but silently waited his opportunity, and retaliated because his duty and his law required it of him.”

|

| Launch of the North West America at Nootka Sound 1788 C. Mertz source Centre of Study for Pacific Northwest |

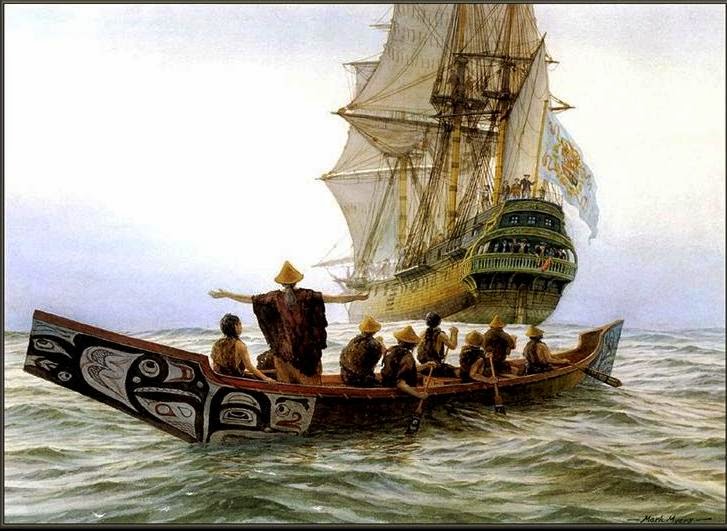

With his faculty for the languages, Sturgis’ dealings and contact with the Indians increased. He ensured he acted with complete honesty and openness to his Indian counterparts and, in consequence, often acquired more goods than your average trader, as the Indians were more amenable to people whom they liked. In fact, Sturgis became a great favourite with some of the Indians, sometimes to his detriment. One old Indian woman, to whom he gave the appellation, Madame Connecor, claimed, “All white men are my children,” and insisted on hugging him and kissing him in public, much to the horror of Sturgis, who had to submit to this uncomfortable display of affection as “her tribe had many valuable furs to sell ……. (I) had no escape.”

Sturgis became quite familiar with a Indian chief named Keow (or Cow), whom he quite admired and they struck up a perhaps unusual friendship:

“Keow was upon the whole the most intelligent Indian I met with. He was a shrewd observer of quick perceptions —– with comprehensive and discriminating mind, and insatiable curiosity. He would occasionally pass several days at a time on board my ship, and I have often sat up half the night with him, answering questions, and listening to remarks. …. his comments upon some features of our social system, and upon the discrepancies and inconsistencies in our professions and practice as Christians —- particularly in relation to war —- duelling —- capital punishment for depredations upon property, and other less important matters, were pertinent and forcible, and by no means flattering to us, or calculated to nourish our self conceit.”

|

| Puget Sound on the Pacific Coast (1870) Albert Bierstadt source Wikiart |

Yet, in spite of his good relations with the native people, Sturgis showed quite clearly that there was a careful balance that needed to be maintained in relations that often included lying, manipulation and trickery, a sort of dance practiced by both parties, accepted by both, and neither held in contempt or begrudged. It was a meeting, or indeed a confrontation, between two different cultures and attitudes that required patience, skill, wisdom and ingenuity to lay a viable foundation.

Later in the voyage, when the Eliza came across two other ships the Despatch and the Ulysses, they found the Ulysses in a state of mutiny and the officers of the two other ships had to arbitrate the dispute. It was agreed that the captain (Lamb) should be reinstated, with Sturgis, only a few month’s previously an amateur sailor, as his second officer. The appointment was an enormous boost for Sturgis’ career. The Ulysses continued to trade in furs, but when it eventually met up with the Eliza in Macao, Sturgis was happy to rejoin his old ship as third mate.

Sturgis also shares some fascinating information on the Indian female and comparisons to his own class.

“The females have considerable voice in the sale of the Skins, indeed greater than the men; for if the wife disapproves of the husband’s bargain, he dares not sell, till he gains her consent, and if she chooses she will sell all his stock whether he likes it or not, or rather what she likes, he is obliged to approve of or afraid to disapprove of ………. In fact, the power of the fair sex seems to be as unlimited on this as on our side of the Continent …..”

Very intriguing that Sturgis sees his fellow women as having unlimited power ….. and this is 1799!

On his second voyage, this time on the ship Caroline, upon the death of its captain, all responsibility was turned over to Sturgis who returned the ship complete with profits from 3000 skins. When the ship return to Boston, he was officially made the master of it at twenty-two years old.

|

| source GoHaidaGwaii |

His third voyage was another success for Sturgis, and when he set out on the Atahualpa on his fourth voyage, it was not only as the commander of the fleet, but as a shareholder. His status and wealth continued to increase and in 1810 he abandoned his nomadic life at sea to marry Elizabeth Davis and became a partner in a shipping business called Bryant and Sturgis. From the years 1818 to 1840, their company directed more than half the business carried on from the United States to California.

Sturgis was seen as a laconic and somewhat stern man, but he was well-respected and lived life with a strong sense of duty and honesty. He died at the age of eighty-one and his eulogies and obituaries speak to his character:

” ….. his cool judgement and his considerable action under difficulties, stamped him as an uncommon man; and his extensive knowledge and his judicious inferences from it, made him a useful one ….. Hi strong intellect and clear judgment made him a wise and safe counsellor. Singularly independent and honest in the formation of his opinions; unswerving in fidelity to his convictions; of an impulsive temperment, guided by principle and made amenable to conscience, —- his character and career, honorable to himself and beneficial to others, leave his name to be held in remembrance as that of a wise, just, faithful and benevolent man …..”

In his final lecture, Sturgis expresses gratitude, that he had not caused any acrimony or bitterness in his dealings with the native population:

“I have cause for gratitude to a higher power —– not only for escape from danger, but for being spared all participation in the deadly conflicts and murderous scenes which surrounded me. I may well be grateful that no blood of the red man ever stained my hands —- that no shades of murdered or slaughtered Indians disturb my repose —– on the reflection that neither myself, nor any one under my command, ever did, or suffered, violence or outrage, during years of intercourse with those reputed the most savage tribes, gives me a satisfaction in exhange for which wealth and honours would be dust in the balance.”

The integrity and honour Sturgis showed towards a native population, while being willing to alter his worldview to meet them on equal grounds, truly speaks to his character. Sturgis is a man I would have certainly been proud to know.