Yearly Archives: 2015

Father Brown: The Worst Crime in the World by G.K. Chesterton

Father Brown has plans to meet his niece in a picture gallery, but before he finds her, he encounters lawyer Granby who wants his opinion. Should he trust a certain Captain Musgrove enough to advance him money on his father’s estate? The estate is not entitled and it is not conclusive that Musgrove Jr. will be the heir. Upon the arrival of his niece, Father Brown learns that she is planning to marry the same Musgrove and meets the young man himself. Musgrove invites both Father Brown and Granby to his father’s castle, but then bows out of the trip at the last moment due to an arrival of a couple of shady characters in the background, but encourages the men to make the trip without him.

After they arrive at the castle (having to leap the moat due to a rusty, disabled drawbridge), they meet Old Musgrove, who assures them that his son will inherit, yet he will never speak to him again, due to the fact that he perpetrated the worst crime in the world. Granby returns to town, secure in his knowledge, but Father Brown remains in the village, determined to discover the details of this dastardly crime. Will he be able to discover the truth in time to save his niece from the clutches of a villain, or is the old man merely playing with him and there is nothing sinister about his son? You will only find out, if you read the full story which can be found here: The Worst Crime in the World – G.K. Chesterton

|

| source Wikimedia Commons |

I love Chesterton’s Father Brown mysteries and this one does not disappoint.

Deal Me In Challenge #12 – Seven of Clubs

Sonnet XXIX by Garcilaso de la Vega

Born in Toledo in 1501, de la Vega was one of the first Spanish poets to introduce Italian verse forms and techniques to Spain. Mastering five languages as well as having a good aptitude for music, de la Vega eventually joined the Spanish military and died at 35 years old from a wound sustained in battle in Nice, France. His poetry has been fortunate to be consistently popular during his life and up until present times.

In Sonnet XXIX, de la Vega explores the Greek myth of Hero (Ὴρὠ) and Leander (Λὲανδρος). Each night Leander swam the Hellespont (the modern Dardanelles) to be with his lovely Hero, who lived in a tower in Sestos by the sea. She would hang a lamp for him in her high tower to guide his path, however, on a particularly stormy night, the waves buffeted Leander, the wind blew out Hero’s lamp, and brave Leander tragically drowned in the raging waters. Bereft, Hero threw herself from her tower into the pitiless sea, which joined them in death, as it had kept them apart in life.

|

| Hero and Leander (1828) William Etty source Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Hero and Leander (1621/22) Domenico Fetti source Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Hero finding Leander (c. 1932) Ferdinand Keller source Wikimedia Commons |

Deal Me In Challenge #11 – Four of Diamonds

Join the Beowulf Read-Along !

An number of months ago, Cat from Tell Me A Story, Cirtnece from Mockingbirds, Looking Glasses and Prejudices … and I talked about reading Beowulf together in May and, since I’ve already led a discussion on it previously AND I have never hosted a read-along before, I’ve decided to make Beowulf my first official read-along!

From Wikipedia:

Beowulf is an Old English epic poem consisting of 3182 alliterative long lines. It is possibly the oldest surviving long poem in Old English and is commonly cited as one of the most important works of Old English Literature. It was written in England some time between the 8th and early 11th century. The author was an anonymous Anglo-Saxon poet, referred to by scholars as the “Beowulf poet”.

Beowulf has a certain amount of controversy attached to it, in that there is disagreement over whether the poem was altered, and therefore over what the poet was attempting to convey. J.R.R. Tolkien has a wonderful essay on Beowulf, called The Monster and the Critics, where he addresses some of these issues and more. I encourage participants to read it to give you some background for the poem.

I’ve decided to run this read-along a little differently than most other read-alongs. At the beginning of each week, I’m going to post some information with regard to the section of the poem that we’re reading. Nothing too fancy, but just some thoughts, ideas, vocabulary and questions to help readers target certain aspects of the poem that make it unique and interesting. In this way, I hope participants will get the most out of the poem and gain an appreciation for a wonderfully tragic, yet uplifting, Old English tale.

Translations:

As for translations, I’ve found Seamus Heaney’s version a highly enjoyable read; it even comes in an audiobook version with Heaney himself reading; the drawback of the second choice is that it’s abridged and in one particular section misses a part that I think is important to gain a deeper understanding of the poem. J.R.R. Tolkien also has a new translation that some may want to try. Unfortunately it’s a prose translation, so while you’ll understand the meaning of the poem, you’ll miss the experience of the beauty of the poetry, which is part of the learning and the enjoyment. The only other translation that I’m familiar with, is that of Professor Lesslie Hall who, I believe, translates the Project Gutenberg edition, and it is considered a solid translation though perhaps more archaic. Translating literature is always a notoriously difficult task and even more so when you’re dealing with Old English poetry. There will be no perfect translation. In spite of some of the criticism of Heaney, I would recommend this edition for first-time readers. For those interested in further investigation into the various translations, please see here.

Schedule:

Now for the schedule. The read will be done over the month of May; the poem is not long and the schedule gives us lots of time to read, so this event won’t be particularly burdensome if you have other books that you’re reading alongside it. I’ll post the line numbers and also a written guide, so those reading translations other than Heaney’s will hopefully know where each section begins and ends. I know that some people enjoy reading at their own pace, but for the maximum enjoyment and for getting the most of out the poem, I encourage everyone to stick to the schedule and read my weekly pre-posts. Plus, it’s fun to read together!

I think that’s all for now. Somewhere around April 26th, I’ll put up a background post to help us get started. So come one, come all, to a journey back in time …….. enter the Mead-Hall, meet the Monster and experience the bravery of one of the most courageous heroes in literature!

(link to original image above)

Beowulf – Background Information

Beowulf Read-Along – Starting Week One

Beowulf Read-Along – Starting Week Two

Zoladdiction 2015 – Here We Go …….!!

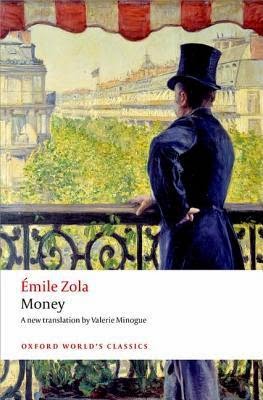

Thanks to Fanda and her wonderful hosting of this yearly event, I have a chance to read from one of my favourite authors, Émile Zola. I’ve been reading through his Rougon-Macquart series, admittedly more slowly than I would like, and I am now set to read book #4, L’Argent or Money.

I’m rather awash in books at present, so my reading may take longer than one month, but I’m going to attempt it. Yet however much I’d like to, sadly I’m not going to take part in the Germinal read-along that is paired with this event, but I encourage everyone else to! Please join, one and all! It’s an event not to be missed!

Classics Club Spin #9

It seems like it’s been a long time between Spins. My last one was a gem ……… Gulliver’s Travels. I can only hope to get a book this time that will live up to Gulliver. He’s going to be a hard act to follow.

As per usual, the rules for the spin are:

- Go to your blog.

- Pick twenty books that you’ve got left to read from your Classics Club list.

- Post that list, numbered 1 – 20, on your blog by next Monday.

- Monday morning, we’ll announce a number from 1 – 20. Go to the list of twenty books you posted and select the book that corresponds to the number we announce.

- The challenge is to read that book by October 6th.

- She Stoops to Conquer (1773) – Oliver Goldsmith

- Erewhon (1872) – Samuel Butler

- Bleak House (1852/53) – Charles Dickens

- The Histories (450 – 420 B.C.) – Herodotus

- Henry V (1599) – William Shakespeare

- We (1921) – Yevgeny Zamyatin

- The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) – Ann Radcliffe

- Wives and Daughters (1864/66) – Elizabeth Gaskell

- The Prince (1513) – Niccolo Machiavelli

- The History of Napoleon Buonoparte (1829) – John Gibson Lockhart

- Invisible Cities (1972) – Italo Calvino

- Twenty Years After (1845) – Alexandre Dumas

- Lives (75) – Plutarch

- Sense and Sensibility (1811) – Jane Austen

- Dead Souls (1842) – Nikolai Gogol

- That Hideous Strength (1945) – C.S. Lewis

- O Pioneers! (1913) – Willa Cather

- The Moonstone (1868) – Wilkie Collins

- The Waves (or other) 1931) – Virginia Woolf

- One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch (1962) – Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Ode To A Nightingale by John Keats

If my memory serves me well, I believe this poem is a favourite of Jason at Literature Frenzy and it was his love of it that inspired me to include it in my Deal Me In Challenge. Without this inspiration, it would probably still be unread, as Keats, for some reason, intimidates my uneducated poetic sensibilities.

-2.jpg) |

| Common Nightingale Source Wikipedia |

|

| The Dryad (1884-85) Evelyn De Morgan Wikimedia Commons |

Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

|

| Illustration of Poem W.J. Neatby source Wikipedia |

Keats initially uses extreme contrasts of his dulled, poisoned senses to the happy nightingale, its song urging him out of his despair; one wonders if it will completely succeed. In the second stanza the poet relates his desire for wine. Why? Because wine is made from grapes, will it allow him to meld more with nature, or does he simply want to get intoxicated to forget his troubles? He admits then that he wishes to escape the suffering of life and expresses regret at the transience of youth and life. Ah, now he claims that he won’t reach the nightingale through wine but poetry, and expresses almost a dualism in that his brain is dull perhaps still with care, yet he is already with the joyous nightingale. The fifth stanza is even more curious. Though he is in the forest with the nightingale, he cannot see the beauty there, as if he can only get glimpes as he is unable to liberate himself from life’s hardship. The poet admits to being “half in love with …. Death,” —- I had thought the poet was equating the nightingale’s song with joy, but now he appears to be marrying it with death. Is this part of his confusion or something deeper that I’m missing? Yet if he dies, he will cease to hear the song, so perhaps he realizes the dilemma. The poet then equates the nightingale with immortality and, as we’ve read, the bird almost transcends earthly constraints; its song has been a continuous joy in a temporal world. But alas, the poet is recalled to his sad state, the nightingale’s song abandons him and he is left to wonder if his whole experience was real or a dream.

|

| Portrait of Keats listening to a nightingale (1845) Joseph Severn source Wikipedia |

This was certainly a difficult poem for a rank amateur. The themes I could pick up were isolation, death, a transcendent joy that perhaps may be unreachable at least for the poet, abandonment, disconnection, transience of life, and a longing for something beyond this life.

As I was reading, I wondered if the poet was trying to match his creative expression with the nightingale’s song. It would seem impossible to create at the level of God, but I felt such inspiration in the poem, almost as if Keats was trying to create the poem as intensely as the poet of the poem was wishing to escape earthly adversity.

I’m no expert, but this poem seems to pair well with Percy Bysshe Shelley’s To A Skylark, which O reviewed recently on her blog Behold the Stars. Both poets put nature front and centre, but Shelley has a much more positive outlook, while Keats’ poem is filled with more nuanced emotions and contradictions. The similarities and contrasts between the two are intriguing.

Deal Me In Challenge #9 – Ace of Diamonds

Confessions by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

“I am resolved on an undertaking that has no model and will have no imitator.”

Rousseau was born in 1712 in Geneva in the Republic of Geneva, a city-state in the Protestant Swiss Confederacy. He was born to a watchmaker named Isaac Rousseau and his wife, Suzanne Bernard, his mother dying tragically mere days following Rousseau’s birth. He described her death as, “the first of my misfortunes.”

“By this dangerous method I acquired in a short time not only a marked facility for reading and comprehension, but also an understanding, unique in one of my years, of the passions. I had as yet no ideas about things, but already I knew every feeling. I had conceived nothing; I had felt everything. This rapid succession of confused emotions did not damage my reason, since as yet I had none; but it provided me with one of a different temper; and left me with some bizarre and romantic notions about human life, of which experience and reflection have never quite managed to cure me.”

|

| Les Charmettes where Rousseau lived with Mme Warens source Wikipedia |

From the age of 10 on, Rousseau saw little of his father, who had moved away to avoid prosecution by a wealthy land owner. The boy was eventually apprenticed to an engraver, but at 15 ran away and began a rather nomadic lifestyle. In Savoy, he would be introduced to Madame Francoise-Louise de Warens, a woman 13 years his senior, whom he would forever call “Maman.” She would be his Muse and surrogate mother for the greater part of Rousseau’s life, as well his lover for a short period of time. Later, his obsessive interest in music would be used to earn money as a teacher, as well as gain him subsequent notoriety as a writer of opera and various other articles and works on the subject.

| Denis Diderot (1767) par Louis-Michel van Loo |

Upon returning to Paris, after a posting in Venice as a secretary to the Comte de Montaigue, Rousseau took Thérèse Levasseur as a lover, eventually having 5 children with her, all of whom he placed in a foundling hospital, being unwilling to bring them up due to the lack of education and undesirable social class of his in-laws whom he was supporting. With his later books on education and child-rearing, these callous actions made him the target of vicious ad hominem attacks from some contemporaries, in particular Voltaire and Edmund Burke.

“As we became better acquainted, we were, of course, obliged to talk about ourselves, to say where we came from and who we were. This threw me into confusion; for I was very well aware that in polite society and among ladies of fashion I had only to describe myself as a new convert and that would be the end of me. I decided to pass myself off as English: I presented myself as a Jacobite, which seemed to satisfy them, called myself Dudding and was known to the company as M. Dudding. One of their number, the Marquis de Taulignan, a confounded fellow, ill like me, old into the bargain, and rather bad-tempered, took it into his head to engage M. Dudding in conversation. He spoke of King James, of the Pretender, and of the court of Saint Germain in the old days. I was on tenderhooks. I knew about all of this only of what little I had read in Count Hamilton and in the gazettes; however I made such good use of this little knowledge that I managed to get away with it, relieved that no one had thought to question me about the English language, of which I did not know one single word.”

“Two or three times a week when the weather was fine we would take coffee in a cool and leafy little summer-house behind the house, over which I had trained hops, and which was a great pleasure to us when it was hot; there we would spend an hour or so inspecting our vegetable plot and our flowers, and discussing our life together in ways that led us to savour more fully its sweetness. At the end of the garden I had another little family: these were my bees. I rarely missed going to visit them, often accompanied by Maman; I was very interest in the arrangements, and found it endlessly entertaining to watch them come home from their marauding with their little thighs sometimes so laden that they could hardly walk.”

|

| Rousseau méditant dans un parc (1769) par Alexandre Hyacinthe Dunouy source Wikipedia |

Rousseau was a man of numerous contradictions. On one hand, he was self-absorbed, petty-minded, overly sensitive, idealistic, peculiar, selfish, out of touch with reality, yet on the other, he was also rather lonely, at times generous, unique, creative, self-aware, and inquisitive. He is a puzzling conundrum bottled up in one person. Yes, he would have been hard to bear at times. He is one of those people with whom one could never be comfortable, as you would always be wondering if you were living up to his standards. He had a short fuse, yet also a generous heart.

How did I come to these conclusions? Well, you certainly get a sense of Rousseau’s perceived persecution that appeared expanded to gigantic proportions in his mind. Many reviewers call this obsession his “paranoia,” an imagined grand plot with machinations designed by numerous former friends, ready to invest years of their lives to bring about his downfall. Yet perhaps this behaviour is not so surprising in a man who had been raised mostly without family, obviously needing the intimacy of human companionship, yet who had never really learned or accepted the proper manners to fit easily in society; French society, in particular, follows certain constructs that do not allow for individuality.

In spite of Rousseau’s various eccentricities, I couldn’t help feel profound sympathy for him. With no one to shape his character and with his unwillingness to temper his idiosyncrasies and become homogeneous with his surroundings, Rousseau became a victim of himself, a plight for me that only excites pity.

Top Ten Tuesday: 10 Books from My Childhood That I’d Like to Revisit

Another fun topic from The Broke and the Bookish, and another late posting. But I just couldn’t miss posting on children’s books, one of my favourite genres. I just wonder if I’ll be able to keep the list at ten only.

1.

Flip The Story of An Otter is an obscure book but an old one which I loved when I went to elementary school. In fact, it’s the first book I actually read as a child, and the library card was full of my name and no one else’s. That in itself shows how much I loved reading it.

2.

Swallows and Amazons absolutely mesmerized me. From the holiday in the Lake District, to camping on an island, to a war with savages, not to mention a scary pirate, this book is certainly at the top of my list. If I could time travel I think I’d choose this time period and this particular area in England. Pure fun!

3.

What is a Moomin? A white, snuggly, Hippo-like creature who completely captivates your imagination. There is nothing more exciting than following Moomintroll and his family on their adventures, and meeting their group of rather eclectic friends, from the Hemulen the botanist, to the Muskrat the philosopher. This book is a brilliant imaginative creation and certainly a childhood favourite.

4.

Milo and Tock go together like bread and butter, and what could make up a better story than one made from letters and numbers in a creative soup of adventure. The mission? To rescue Rhyme and Reason, yet what can a rather apathetic boy and a ticking dog do? Read and you will discover!

5.

Persuasion by Jane Austen

“Sir Walter Elliot, of Kellynch-hall, in Somersetshire, was a man who, for his own amusement, never took up any book but the Baronetage; there he found occupation for an idle hours, and consolation in a distressed one ……”

Persuasion was the only major Austen novel that I had not read, so I was thrilled when Heidi at Literary Adventures Along the Brandywine announced her read-along. I wasn’t expecting to enjoy the novel quite as much as Pride and Prejudice, one of my favourites, but I’d heard enough positive reviews to whet my curiousity. And so I plunged in.

Anne Elliot is one of three daughters of Sir Walter Elliot, a vain baronet who is obsessed with the peerage. While her sister, Elizabeth, is somewhat bossy, and Mary proves a proud, yet questionable, invalid, Anne shows a quiet reserve with more than average good sense and judgement. Eight years ago, her engagement to Captain Frederick Wentworth was almost certain, but without a mother for guidance, and influenced by a respected friend of the family, Lady Russell, she broke off the engagement with a deep regret.

|

| Manor House, Somersetshire (Halsway Manor) source Wikipedia |

Now, eight years later, Anne is confronted with a number of upheavals in her life. Not only does she and her family have to leave their ancestral home, Kellynch-hall, because of reduced finances, but Captain Wentworth has returned, and to further complicate matters, his sister and her husband are the new tenants of Kellynch-hall. The blows would have reduced a weaker woman to despondency, but Anne is not only resourceful, she has learned to suffer life’s troughs with resilience, and her positive attitude brings her through the stormy seas.

Initially, Captain Wentworth is all resentment and cool responses, but gradually, as he sees Anne’s quiet sacrifices, calm demeanour, and strength of character, his acrimony softens towards her. Yet, at the same time, he appears to be playing the eligible bachelor, and it is uncertain as to which woman he will chose to be Mrs. Wenworth. Both of Anne’s sisters-in-law, Henrietta and Louisa, vie for the title and Anne must watch the perceived courtships with an uneasy mind. A near-tragedy causes introspection in more hearts than one, Mr. Eliot, Anne’s cousin and heir to Kellynch, enters the picture to further obscure the matters of courtship, but the final culmination exemplifies that a steadfast love is strengthened by misfortune and time, and the past lovers reunite in a now more matured and seasoned alliance.

|

| Lyme Regis |

Persuasion is a tale of new beginnings and second chances, not only for Anne and Wentworth, but for the characters surrounding them. Anne’s family, because of their financial straits, must begin a new life in Bath; both the Musgrove girls will be looking forward to the start of their married lives; and even Mrs. Smith, who has found herself in poverty after her husband’s death, is given a second chance at the end of the book as, with help from Wentworth, she recovers money from her husband’s estate that will help her to live more comfortably.

While Austen, as per her usual method, allows the reader to examine certain segments of society, in this book especially, she seems to be highlighting the movements between the social classes, either by marriage or by economic necessity. Within Anne’s family, we not only have the family as a whole dropping in perceived standing by the lack of money to maintain their position at Kellynch, we also have the numerous characters dealing with the descent with different outlooks. Sir Walter is obsessed with his Baronetage book and the importance of his place within the realm of society. At first, he employs denial as to their new position, but thanks to a rather blind self-importance, is able to be persuaded to accept their new situation as if nothing has practically changed. Anne’s sister, Elizabeth, too, acts as if nothing has altered, yet you can see at certain points in the novel that she is aware of the disadvantage of their new situation and that they must have a heightened awareness of appearance to maintain the respect and dignity that they view as a societal necessity. Anne does not seem to be bothered by the family’s reduced circumstances, as position to her comes secondary to character and honesty and integrity. In the old governess, Mrs. Smith we can examine what has come from her rise in stature upon her marriage, and then her subsequent fall upon her husband’s death when she finds herself in financial troubles. Finally, cousin William Elliot falls from his seat of grace with his scandalous behaviour at the end of the novel.

|

| Pulteny Bridge, Bath 18th century source Wikipedia |

We are given the title of Persuasion for the book, yet Austen did not choose this title; instead her beloved brother, Henry, gave the book its name, as it was published posthumously, and there is no indication of what Austen’s preferred title would have been. Cassandra Austen, Jane’s older sister, reportedly said that a name for this novel had been discussed, and the most likely title was “The Elliots,” but as Austen passed away before selecting a definitive title, no one will know for certain her final choice. Nevertheless the word “persuasion”, or a derivative of it, occurs approximately 30 times in the novel, a good indication that it is one of the main themes. Yet as I finished the novel, what metamorphosed out the “persuasion” was the stronger theme of duty. While Wentworth still appears to be disgruntled by Anne’s choice to follow her family’s wishes in breaking off their engagement eight years before, she however appears to have a different sentiment. At the end of the novel, Anne concludes:

“I have been thinking over the past, and trying impartially to judge of the right and wrong, I mean with regard to myself; and I must believe that I was right, much as I suffered from it, that I was perfectly right in being guided by the friend whom you will love better than you do now. To me, she was in the place of a parent. Do not mistake me, however. I am not sayng that she did not err in her advice. It was, perhaps, one of those cases in which advice is good or bad only as the event decides; and for myself, I certainly never should, in any circumstance of tolerable similarity, give such advice. But I mean, that I was right in submitting to her, and that if I had done otherwise, I should have suffered more in continuing the engagement than I did even in giving it up, because I should have suffered in my conscience. I have now, as far as such a sentiment is allowable in human nature, nothing to reproach myself with; and if I mistake not, a strong sense of duty is no bad part of a woman’s portion.”

In the book Anne is consistently dutiful, to her friend, Mrs. Smith, to her family and, more importantly, to her own conscience; and so we learn that a strong sense of duty and obedience to it is more crucial than any personal inclinations or aspirations.

|

| Sandhill Park, Somerset (1829) J.P. Neale/W. Taylor source Wikipedia |

Persuasion deviates from Austen’s usual style and content. By having a hero without ties to nobility, Austen explores in depth an area of society that had to date been given only a cursory treatment by her. Anne, as an older heroine, is presented in a new way; the reader learns of her character not necessarily through how she actually behaves, but more through her silence and by seeing her in contrast to the intensely flawed people around her. Contrary to other Austen novels, the romance develops almost in isolation, as the characters hold little conversation with each other until the end of the novel. While the novel was interesting for these new features, I felt it to be weaker than Austen’s previous novels, lacking a certain plausibility at times and a solid cohesiveness. As she was writing Persuasion, Austen was ill with the disease that would eventually kill her, and because of this fact, her usual detailed pattern of revision was not completed; in this light, the diminished quality of the novel can certainly be understood. However, while not shining with her usual brilliance, Austen still produced a jewel in its own right, and perhaps more intriguing because of its flaws, as these flaws contribute to its uniqueness. As the character of Anne experiences a new beginning in Persuasion, so does the novel indeed appear to symbolize a new beginning by Austen, this beginning sadly cut short due to her untimely death.

.jpg)