.jpg) |

| First Edition Dust Jacket source Wikipedia |

“This is the story of an adventure that happened in Narnia and Calormen and the lands between, in the Golden Age when Peter was High King in Narnia and his brother and his two sisters were King and Queens under him.”

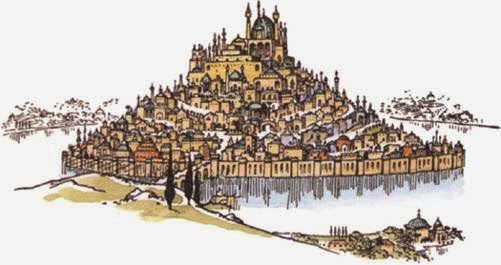

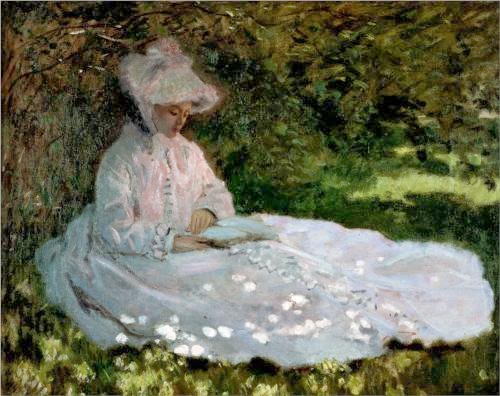

Elements of The Arabian Nights permeate this story. Calormen is reminiscent of an Arabian city, and the people are perceptive, knowledgeable, wealthy and courteous, yet a ruthlessness runs through their ancient blood. They are also respected storytellers, able to weave elaborately fabulous tales.

From another viewpoint, the storyline could be compared to a Shakespearean drama. Lost or mistaken identity are favourite devices of the Bard, and Shasta’s situation fits just this scenario: a boy who has been taken from his parents, discovers he does not belong within the culture where he lives, and sets out to find out his true heritage.

And finally, a prophecy is given at the beginning of Cor’s (Shasta’s) life, that he will one day save Archenland from a terrible catastrophe. This prophecy is reminiscent of the Greek story of Oedipus told by Sophocles: a prophecy is given at his birth as well and, as in the case of Cor, every attempt to prevent the prophecy, only causes its fulfilment.

|

| Tashbaan by Pauline Baynes (1953) |

Instead of Aslan appearing outright to the children as in other stories and directly affecting the adventure, in The Horse and His Boy, he is presented as a shadowy presence that hovers at the edge of the adventure. Finally he does intervene but the book makes it very clear that his actions are still behind the story not driving it. When Aravis remarks that it is “luck” that she was not more seriously wounded by the Lion, the hermit replies, “…. I have never met any such thing as luck”; instead of fortune, it is Aslan or Providence that is helping them on. As Shasta so wisely remarks, ” ……. Aslan (he seems to be at the back of all stories) …..”

I believe there is also some “reverse-theology” incorporated into the making of the characters of Shasta and Aravis. Aravis is strong and courageous; she is adept on a horse, knows her mind, and often mocks or secretly despises some of the tentativeness or perceived weakness shown by Shasta. Yet, at the climax of the story, it is Shasta who shows unexpected bravery and is ultimately trusted with the task of saving Archenland from the troops of Rabadash. Aravis is forced to admit her pride, which she does most willingly: “There’s something I’ve got to say at once. I’m sorry I’ve been such a pig. But I did change [her opinion of him] before you were a Prince, honestly I did: when you went back, and faced the Lion,” echoing the biblical maxim, “for those who exalt themselves shall be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.”

The Magician’s Nephew is up next. It used to be my least favourite chronicle but we’ll see if the years have changed my mind!

.jpg!Blog.jpg)

-ulema.png)