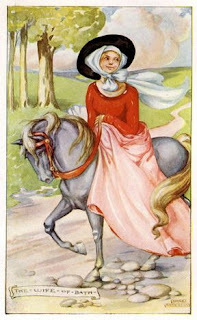

The Wife of Bath’s Prologue is by far the longest prologue in The Canterbury Tales. From The General Prologue, we learned that she has a fabulous skill in weaving cloth and exceeds abilities of the weavers in the well-known Belgium clothing-making centres of Ypres and Ghent. Her fashion is rather flamboyant, as she is clad in nearly ten pounds of cloth, rounding out her ostentation with scarlet stockings. And while she’s somewhat deaf, she certainly has no aversion to talking. Love is her specialty.

This “good” Wife immediately tells us that she has been married five times since she was twelve years old. Yikes! And in spite of some Biblical references that perhaps discourage this practice, there are a good number of examples of men with many wives, so why not she? The fact that she’s been often married, qualifies her to speak on the subject as an expert, or so she believes. She argues for marriage, using many extraordinary arguments. The organs of men and women cannot simply be for eliminating urine and determining male from female. No! The Wife of Bath claims experience teaches otherwise.

She uses many Biblical references and those from ancient writings with impunity, agreeing or disagreeing to suit her philosophy and purpose. While illustrating the difference between wives and virgins, she describes virgins as white bread and wives as barley bread; since Jesus himself used barley bread to feed the five thousand, therefore wives are of much more value.

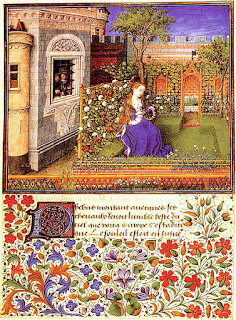

The Wife passes over most of her husbands, only sharing that most of them were rich and old, yet she stays to describe the marriage to her fifth husband whom, despite his ill-treatment of her, she appears to have loved. Jenkin is his name and he spends much of his time reading from a book that portrays the exploits of wicked wives. In frustration, the Wife tears out pages from the book, and in enraged retaliation, her husband strikes her:

“And when I saw that he would never stop

Reading all night from his accursed book,

Suddenly, in the midst of it, I took

Three leaves and tore them out in a great pique,

And with my fist I caught him on the cheek

So hard I tumbled backward in the fire.

And up he jumped, he was as mad for ire

As a mad lion, and caught me on the head

With such a blow I fell down dead.”

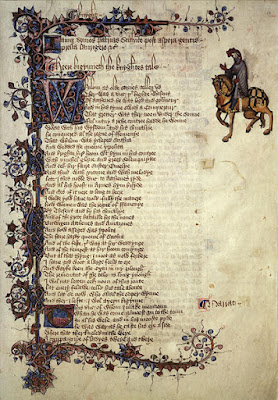

Middle English:

|

| source |

The Wife of Bath’s Tale

Set in the gloriously noble times of King Arthur, the wife tells the story of a young knight who is accused of the rape of a maiden. He is taken to Queen Guinevere, who proclaims that he will gain a reprieve if, within the space of one year, he can discover what women most desire.

A year passes and the knight, despondent at not discovering an answer, returns to Camelot. On his way, he meets an old grizzled hag who promises to reveal the answer if he will grant her whatever she asks. She whispers in his ear, and the knight returns to Queen Guinevere professing that “women desire to have the sovereignty and sit in rule and government above their husbands, and to have their way in love.” The knight is pardoned, but his joy is short-lived, as he discovers that the old woman wishes to be his wife.

His lack of enthusiasm in bed displeases his new wife and she lectures him on virtue; it is not attained by wealth, appearance or status, but rather is cultivated by character. She could transform herself to correct the issues that disgust him, but does he want an old, virtuous, faithful wife, or a beautiful young wife who could easily make him a cuckhold? The knight allows her to choose, and because he has given her this power, she makes herself both faithful and beautiful. The knight is overjoyed and all ends happily.

The Wife of Bath must have the final say though and ends with almost a benediction that God would send women young, lusty, submissive husbands, and the plague to those who are irascible and parsimonious.

|

| The Overthrowing of the Rusty Knight (1894) Arthur Hughes source Wikiart |

The Wife of Bath weaves cloth but is also adept at weaving words. Her deafness also seems a rather important point. Not only is she physically deaf, she is deaf to the needs of others, deaf to Biblical precepts, deaf to social convention and even deaf to the consequences of her actions; even though her marriages don’t necessarily bring marital bliss, her troubles do not seem to deviate her from her set course. This Wife means to make war on and conquer her husbands. Yet the mastery she seeks is not a forced control; she means to coerce a yielded power, in that the man willingly gives all control to her, domestically, economically and personally. This “good” woman shows no discomposure in depicting herself as a wife who uses accusations for torment, withholds sexual favours for payment and gains mastery over her husbands by force, nagging and trickery. In fact, she glorifies in it.

The Man of Law’s Tale

The Wife of Bath’s Tale

The Friar’s Tale

The Summoner’s Tale

The Clerk’s Tale

The Merchant’s Tale

The Squire’s Tale

The Franklin’s Tale

The Physician’s Tale

The Pardoner’s Tale

The Shipman’s Tale

The Prioress’s Tale

The Tale of Sir Thopas

The Tale of Melibee

The Monk’s Tale

The Nun’s Priest’s Tale