|

| Farmhouse and Car (1933) Prudence Hayward source Wikiart |

Imagine a small town in the southern United States on a hot day. An old woman and her daughter sit on the front porch of their house, the woman suddenly alert while the daughter plays vacantly with her fingers. Down the road, a man materializes, a young man but by his appearance obviously a drifter. He has “a look of composed dissatisfaction as if he understood life thoroughly.” The woman and man greet each other, each eyeing the other with a hesitant speculation and a mutually concealed distrust. After an introduction, the woman tries to find out more about Mr. Shiftlet but the man adeptly avoids answering, speaking of cars, hearts, lying and the definition of man. With more talk, it becomes clearer that the man is interested in the old car in the yard that had belonged to the woman’s deceased husband, and the woman is interested in a suitor for her mentally disabled daughter. Agreeing to stay on for board and food, the man begins to spruce the place up and soon it looks much improved.

As time passes, the woman continues to subtly bargain for a husband for her daughter, as Shiftlet counters, bargaining for the car. Finally a deal is struck, the two marry and the car becomes his. Yet the material desire of his heart is at war with the obligation to his new unwanted wife. Shiftlet finds himself with a choice and the struggle within himself is powerfully displayed.

This story was perplexing, and although I haven’t read any of O’Connor’s other works, I have a feeling that she regularly creates confusion with readers. While reading The Life You Save May Just Be Your Own, I was struck with impressions rather than feelings, as if I was following an incohesive story. The story is there, but O’Connor inserts so many phrases that are pregnant with meaning, that you simply can’t help analyzing them, wondering if there is some sort of secondary communication. Let’s see what I can make of it.

|

| The Farmer’s Daughter (1945) Prudence Heward source Wikiart |

First of all, does Mr. Shiftlet’s name imply that he is a “shifty” character, or does it indicate a possibility of shift or change within him? Or both? Initially, he is presented swinging “both his whole and his short arm up slowly so that they indicated an expanse of sky and his figure formed a crooked cross.” There is definitely religious connotations here, but notice the “crooked cross.” There is certainly something very imperfect about this man. He is also a carpenter, which was the profession of Jesus — does that mean anything or not? When the woman tells him that he must sleep in the car, Shiftlet answers, “Lady, the monks of old slept in their coffins.” Here is another allusion to religion and death (although monks slept in their coffins so they would get used to not fearing death, but that’s another story).

O’Connor also employs colour imagery in profusion, from the bright colours around Lucynell, the daughter, indicating innocence, purity and happiness, to the black, brown and grey colours worn by the man and woman, from the sun shining forth at the beginning of the story, only to be covered by a cloud at the end.

|

| Portrait of a Man (1911) Albert Bloch source Wikiart |

There is much speculation as to what O’Connor wanted to convey with this story, and there certainly appears to be deeply imbedded layered meaning. When writing, O’Connor applied a type of analogical technique that allowed to reader “to see different levels of reality in one image or situation ….. (having) to do with the Divine life and our participation in it ….. was also an attitude towards all creation, and a way of reading nature which included most possibilities and I think that it is this enlarged view of the human scene that the fiction writer has to cultivate if he is every going to write stories that have any chance of becoming a permanent part of our literature.”

For me, the impression that stood out was the subtle change in the man. Initially, he is a tramp, someone who is disconnected to the material, content to wander and take odd jobs. His exchange with the woman borders on the philosophical on his side and he is likened to a Christ-like figure. Yet as soon as he espies the car, a possessive desire begins to simmer inside him, causing him to abandon his ideals, and he is satisfied to barter with the mother for Lucynell as if she were an animal or possession. Because his attention is fixed on a worldly goal, Shiftlet becomes blind to simple pleasures and human empathy.

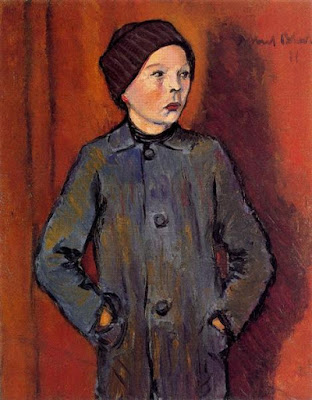

|

| Portrait of a Boy Albert Bloch source Wikiart |

If nothing else, O’Connor gives the reader a multitude of possibilities and honestly, this short story was a compelling and intriguing experience.

Next week, for my Deal Me In Challenge, I’ll be reading the short story by Virginia Woolf, A Haunted House.

Week 7 – Deal Me In Challenge – Six of Clubs