My, it’s been a long time since I posted on an essay/talk from this project. Even though I was so excited to get to the next section on love, this series on Darwin finally stalled me. It was interesting but after 4 essays delving into Darwin and evolution, I was approaching a stupor. So with some time passed, I’m determined to get through this last essay!

Category Archives: Author: Adler

The Great Ideas ~ The Answer to Darwin

In The Darwinian Theory of Man’s Origin, Adler of course explained Darwin’s theory of evolution and the evidence that anchors it. Here in The Answer to Darwin, he continues with the evidence, adds to it more current research and the gives some evidence of his own to the contrary.

Adler reminds us that Darwin never built his theory on the anatomical or physiological resemblance between the higher animals and man, nor embriological similarities or fossils. He rested his whole argument on mental power, in respect to the differences and similarities. “The difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.” What evidence did Darwin use for his conclusion? It is all on the basis of human and animal behaviour. He claims animals reason, use tools and use speech the same as man but to a lesser degree. Adler then gives examples of experiments of animal behaviour since Darwin’s day, all seemingly to support Darwin’s theory. But Adler does not believe they are indisputable and he is going to dispute them. He believes that men differ essentially from all other animals in kind, and his evidence will be presented under three different headings:

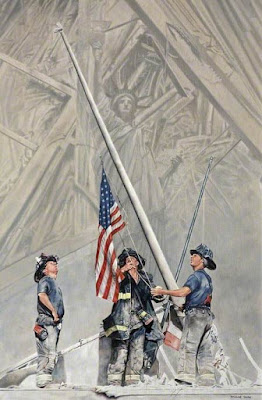

- Only humans make artistically

- Only humans think discursively

- Only humans associate politically

The Great Ideas ~ The Darwinian Theory of Man’s Origin

From How Different Are Humans? we move to the Darwinian Theory of Man, the argument and evidence for his origin and nature. While Darwin did not present his theory until his second book, The Descent of Man, he relied on his first book, Origin of Species for the truths of his theory.

The Great Ideas ~ How Different Are Humans?

The discussion continues from How To Think About Man, with the examination of the two questions, the nature of man and the origin of man. In the last talk/essay, both opposing views were presented: before Darwin man was seen as having a special, distinct nature, but after Darwin he is see only differing in degree from other animals but is otherwise the same.

Adler wishes to approach this issue logically as it is important to see the issue clearly in order to access both arguments. Luckman says that they have received letters criticizing Adler for taking the side of Darwin and Adler expresses his delight. He implies his view is the exact opposite and is pleased with the error as it proves he is so far presenting the argument without any personal bias. He does not plan to argue either for or against any one side, merely to present the issues logically and fairly.

|

| Young Man (The impassioned singer) Giovane uomo (Il cantore appassionato) Giogorgione source Wikiart |

Differences in Kind and Differences in Degree

Adler begins with the definition of man. There have been many definitions, but defining him as a “rational animal” is the most accurate, as it underlies all the other definitions. However it is not the definition but the interpretation of it that is the issue as it implies humans alone are rational.

Adler moves to the distinction between “kind” and “degree” which is important to understand to move ahead in the examination of the issues. He gives an analogy of two lines of different lengths. They have the same traits, only one is longer and one is shorter. They differ in degree. However, a circle and a square do not have common traits — one has angles and one does not — their differences are differences in kind.

Luckman says many scientists believe that the difference between kind and degree, is itself a difference of kind or degree; he gives the example of a many-many-sided polygon which eventually approaches and appears like a circle. Adler does not agree with this statement. No matter how closely the polygon will appear like a circle, it will never be a circle; “difference in degree is never difference in kind and vice versa.” When two things differ in degree, there always can be intermediates, such as an intermediate line between the two in his above example, but there is no intermediates between differences in kind. They can have things in common, but there will always be a property or charcteristic that the other completely lacks. The one with the additional property will be hierachically above the other.

Luckman interjects, saying that it seems that Adler’s definition of difference in kind is accepted by evolutionists and he wants to know how Adler thinks they differ. After all, apes are different from horses and therefore so must man be different. He does not see the issue. Adler says there is one, and he intends to make it clear.

|

| Man and Ape Stanley Pinker source Wikiart |

Differences in Kind Exclude Intermediate Forms

Adler claims Luckman made a misstatement and although the evolutionists do see some forms of life as lower and some higher, they believe they differ only in degree. How does Adler know this? Because evolutionists believe in the continuity of nature. There would be “no underlying continuity in nature …. unless intermediate varieties were possible as between different species in the scale of thing or the greater things”. These intermediate varieties must be possible, even if they are only missing links. Those species which the biologist classifies as kinds are only apparent kinds, yet with the definition of man, they are real kinds.

Adler offers two conceptions:

- a conception of species with missing links between them, with intermediate varieties

- a conception of species without any missing links or without any intermediate varieties

The present biological understanding is that species are only apparent kinds, separated by the possibility of intermediate varieties and therefore can be a difference in degrees.

One more fact, modern science has hypothesized that if all possible forms of life or every species ever know existed on earth at the same time, there would be no species, just individual differences in degree. The philosophical conception is species are real kinds with no intermediate varieties; modern biology sees the kinds with a possibility of intermediate varieties.

We get back to the question of how man differs from other animals: if in kind there is no intermediate varieties possible, but if in degree there are possibilities of intermediate varieties.

Adler emphasizes that so far he has only presented the facts without prejudice to one side or the other. Next time, he is going to present the evidence and arguments from the evolutionist’s point of view, that man only differs in degree which sets the stage for natural evolution. He will then produce arguments and evidence for the opposing side, that man differs essentially in kind which would make a natural evolutionary process impossible.

Phew! This talk became hard to follow about halfway through but I do believe I get Adler’s point. His next essay/talk is The Darwinian Theory of Man’s Origin.

The Great Ideas ~ How To Think About Man

As I start my sixth lecture/essay of Adler’s, we are moving from the examination of knowledge and opinion to the nature of Man. Adler is appearing to take one idea and have five lectures that focus on it, and so far I’m really impressed by the way he logically and reasonably develops his arguments.

- With regard to man’s nature, is man different or different in some degree from animals?

- With regard to man’s origin in that, is he a created or an evolved being?

Adler agrees that there is a lively division between science and religion with regard to the views of man’s nature and origin, but he wishes to speak outside of the religious scope and simply wants to address that the traditional view of man has had very little defense. Apart from faith, there has been very few who have stood against Darwin’s theory “on the grounds of reason or in terms of the facts and the interpretation of the facts.”

|

| The Three Ages of Man (1500-1501) Giorgione source Wikiart |

Before and After Darwin

“What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason! How infinite in faculty! In form, in moving, how express and admirable! In action how like an angel! In apprehension how like a god! The beauty of the world, the paragon of animals.”

“A creature whom not prone and brute as other creatures, but embued with sanctity of reason might erect his stature and upright with front serene govern the rest, self-knowing and from thence magnanimous to correspond with heaven.”

The opposite point of view did not become popular until the end of the nineteenth century, although as early as the sixteenth century people such as Machiavelli and Montaigne introduced the idea that man was no better than beasts. It is the biology, psychology and science of modern times that have entirely altered society’s perception of man. Sigmund Freud points to three men who have fatally injured man’s traditional view: Copernicus who displaced man from the centre of the universe; Darwin with his research stole man’s special privilege of a created being; and himself, who said, “Humanity has in the course of time had to endure from the hands of science two great outrages upon its naïve self-love ….. But man’s craving for grandiosity is now suffering the third and most bitter blow from present-day psychological research, which is endeavoring to prove to the ego of each one of us that he is not even master in his own house, but that he must remain content with the various scraps of information about what is going on unconsciously.”

Luckman interjects asking if Adler is going to deal with Copernicus and Freud instead of Darwin, but Adler confirms that his focus will be on Darwin for he feels he has made the only serious attack on the traditional view of man.

|

| Study for ‘Man and Nature’ (1987) Stephen Conroy source ArtUK |

How Are Human’s Different From Other Animals?

Copernicus does not essentially attack the view that “man differs in kind essentially and radically from other animals,” and Freud does so only from the perspective that he is a follower of Darwin, so Darwin is the true obstacle.

Bear with me here because he gives a quote of Darwin’s:

“The difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, is certainly one of degree (Adler directs us to notice the word ‘degree,’ and not of ‘kind’.) ……. We have seen that the senses and the intuitions, the various emotions and faculties such as love, memory, attention, curiosity, imitation, reason, of which man boasts, may be found in incipient or even sometimes in a well-developed condition in the lower animals. They are also capable of inherited improvements …… If it could be proved that certain high mental powers, such as the formation of general conceptions, were absolutely peculiar to man …… “ which Darwin doubts, and claims that man merely has a higher language than other animals.

Now Adler say that, apart from the question of God’s existence, this question about the nature and origins of man is the most serious question that can be considered as it involves all of religion and science and philosophy.

He reminds us that by arguing his points, he is going to make no appeal to faith whatsoever and approach them merely on the terms of science, philosophy and in interpretation of the facts. The facts that will be dealt with have crucial consequences for religion, morals and politics, that are even more serious than the division of culture between the West and the East and the way each views man and animal. He gives examples of the customs of India with regard to monkeys and cattle, then goes on to present a description of a novel by Vercors, You Shall Know Them, where the line between man and animal is blurred and by this uncertain distinction, so is the moral code against killing a human being.

|

| Origin of Species IV (1959) Coqué Martinez source ArtUK |

Man’s Nature and Origin Are Inseparable

Luckman asks is there not two questions: the origin of man, which Adler is discussing, and the nature of man? Are they inseparable, and Adler states they are indeed, although be believes the question of man’s nature is more important than the question of man’s origin.

The contemporary view starts with “an hypothesis about man’s nature, about man’s origin, his evolutionary origin,” which moves to “a conclusion about man’s nature.” The traditional view begins with a conclusion about man’s nature which moves to “some hypothesis about his origin.” Adler believes it’s best to start with man’s nature and then move to his origin. Why? Because we have more observable facts about man’s nature yet more conjectural facts about man’s origin. To start in the reverse order would be “beg(ging) the whole question, scientifically speaking.” Where one begins is of paramount importance.

In the next lecture/essay he wants to devote a good amount of time to the logic of the issue. We need to be distinct when we are referring to “degree” and “kind”. Then he will present Darwin’s point of view, followed by the opposite point of view. Finally he will emphasize the significance of this issue and reveal why everyone must take sides. And even though he has taken a side (which I won’t reveal yet) he is going to attempt to argue the question as fairly and equitably as he is able and he welcomes any objections, happy to include other viewpoints in the argument as well as his own.

Adler’s next essay is entitled, How Different Are Humans?, where he continues his discussion on the nature and origin of man.

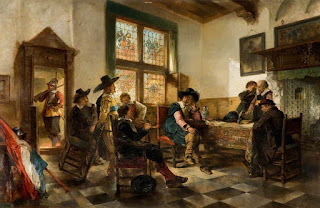

The Great Ideas ~ Opinion and Majority Rule

Opinion and Majority Rule

Adler states that he is going to discuss the problem of majority rule, how the opinions of the majority clash with that of the minority and the controversy about basic social issues. Before he proceeds, he reminds the reader about the issues already considered: that central to opinions we have the freedom with regard to how we act; we also have a right to disagree reasonably about policies, actions, etc., however to live in a peaceful society it is imperative to have means to resolve disagreement, to allow that society to work toward a common goal.

Luckman queries of Adler, why political differences cannot be solved in the same way as disputes in science or philosophy? Adler says it entirely depends on whether one sees science and philosophy as knowledge or opinion; as far as science and philosophy are seen as knowledge, problems can be solved by investigating facts, but because political controversy is seen as opinion, it must be solved in a different manner.

|

| The Attributes of Science (1731) Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin source Wikiart |

Offering a fabricated and implausible example of a Supreme court judge claiming that he can scientifically prove his independent decision, Adler shows that if this were possible, we would not have contradictory opinions, nor the need to vote to determine how the majority stood on issues. It would be equally ridiculous for a mathematician to determine the answer to a problem by taking a vote. However since politics (and judicial matters) are a matter of opinion, voting is the only reasonable way to proceed. Luckman wants to know if there is no other way to settle political differences.

There are two possible ways:

- Force: However force only silences differences of opinion, it does not resolve or eradicate them. It is not a way for reasonable men to behave, as opinions should be heard and settled by debate.

- Autocracy: a majority of society agreeing to give one man the authority to make all the decisions for the society to accept and act on. Adler does not think this way is as reasonable as letting the majority directly make the decisions, which is more conducive to human freedom.

In political freedom there are two integral factors: 1) that the citizens are “governed for their own good for the common welfare of the State,” making men free when they are governed for the good of all and not for private interests; 2) men have a voice in the government who makes the decisions. Citizens of even the wisest monarchy or a judicious despot are never completely free and therefore majority rule, where each citizen has a voice in the decisions, imparts the fullest form of political liberty, which should be a right for all.

|

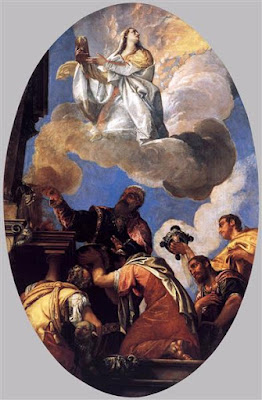

| Wisdom (1560) Ticiano Vecellio source Wikiart |

Luckman counters with examples from Plato and Hegel who thought it was better for men to be ruled by a wise ruler for their own good, as the majority were often misguided and did not make decisions in the best interests of all society. Adler agrees that some of the greatest political theorists have disagreed with majority rule and since it is a matter of opinion, he can only defend his case by producing opinions from some of the most respected minds in history:

“Ordinary men usually manage public affairs better than their more gifted fellows for on public matters no one can hear and decide so well as the many.” ~ Thucydides

“The many of whom each individual is but an ordinary person when they meet together are likely to reach a better decision than the few best men. For each individual among them has a share of virtue and prudence. And when they meet together they become in a manner one man who has many feet and hands and senses and minds. Hence the many are better judges than a single man; for some understand one part, and some another, and together they understand the whole.” ~ Aristotle

“The people of any country, if like Americans they are intelligent and well-informed, seldom adopt and steadily persevere for many years in an erroneous opinion, respecting their interests.” ~ John Jay

“The people commonly and usually intend the public good. They sometimes do make errors, but the wonder is that they seldom do.” ~ Alexander Hamilton

Luckman mentions John Stuart Mill who greatly feared the majority but Adler bring in two quotes of his that appear to prove he accepted the principle of it. Because Luckman brings up Mill’s idea of protecting the minority, Adler then begins to speak about the majority’s responsibility for the opinions of dissenting minorities, implying that we have a problem in how we approach this responsibility in modern times.

|

| Endless Debate Norman Rockwell source Wikiart |

First, there are three ingredients for making the majority responsible to the minority:

- We should never fear controversy but embrace it. We have a moral obligation to seek out controversy, engage in it, and see it as good.

- We should safeguard public debates on public issues and ensure that they never become farcical. When one uses propoganda and dishonest pressure and does not employ rational discussion, it is as bad as using guns and bombs. He says this about the Lincoln-Douglas debates on the hot issue of slavery: “neither side in those debates was intimidated by sinister pressures or counteracted by insidious propaganda.”

- Public debate on public issues should be maintained as long as possible until all sides have been heard and all issues presented. Even when a decision is made there should still be avenues for discussion for those who do not agree with it.

Only when these three elements are employed does majority rule have its fullest positive effect on decision-making. Adler adds a quote from Mill which he believes should be engraved on the heart of every American:

“First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may for ought we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. Second, though the silenced opinion be in error, it may and very commonly does contain a portion of the truth. And since the general or prevailing truth on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only be the collision of adverse opinion that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied. And third, even if the received opinion be not only truth, but whole truth, unless it is suffered to be and actually is vigorously and earnestly contested, it will by most of those who receive it be held in a manner of prejudice with little comprehension or feeling of its rational ground.”

Finally Adler brings up a collision of opinion that he grieves will never be resolved: the difference of opinion between generations. In this “irresolvable dispute”, the older generation because of their life experience and maturity should be wiser than their children but the problem is that the children have not had that experience to be able to find common ground with their parents’ generation, and often irreversible mistakes are made. His final words are compelling: “I regard this as one of the saddest facts about the human race. If we could only do something about this, if we could only find a way of having children profit somehow by the experience of their parents, of accepting somehow the wisdom that is in their parents’ opinions as a result of that experience, I think we could change the course of human history overnight. Progress could be made to move with much greater speed than it ever has in the whole course of human history.”

The next essay is titled How to Think About Man.

The Great Ideas ~ Opinion and Human Freedom

In the last chapter, Adler examined in detail the difference between opinion and knowledge. Now he takes us on another path in examining various problems linked to opinion, but this time in the realm of action rather than the realm of thought.

Opinion and Human Freedom

Luckman prods Adler to investigate another form of skepticism which holds all matters of fact knowledge but all matters of value only opinion. and he brands it as a sociological skepticism. Adler concurs and declares that it would be very difficult to graduate from college or university without being “inoculated with it.” It is the skepticism that questions how any man or society’s opinions can be better than another’s, because the opinions always come from the point of view of that man or society. This skepticism goes back to the Greeks and with Herodotus’ The Histories (which I’m reading at the moment), the Greek sophists argued that everyone was different in how they lived and acted. Science could only explain natural matters but the regulation of society should not be governed by it. In fact, this view was prevalent in the sixteenth century and the discovery of cannibals by Montaigne, who is somewhat the spokesperson for European thought, made him conclude that there was no practice so hideous that man might not only adopt it, but think it good.

When Luckman inquires as to how Adler would answer these types of skeptics, Adler responds that the topic is too broad and would lead them away from the discussion, but he will attempt a brief answer.

Fundamental Values Are Universal

First Adler introduces some facts that the sociological skeptics ignore. While it is accurate that practices vary from society to society or culture to culture, there are also foundational human values that remain constant. John Locke, an English Enlightenment philosopher and physician, illustrated this point well when he said:

“…. there is scarce that principle of morality or rule of virtue which is not somewhere or other slighted or condemned by general fashion of whole societies of men, governed by practical opinions and rules of living quite opposite to others ……. Nevertheless the most general rules of right and wrong, the most general rules of virtue and vice are kept everywhere the same ….”

To explain his point, Adler claims that acts of murder, courage, cowardice are valued or despised in every society, only each society may define each of these acts somewhat differently. For example, some tribes might call a particular killing a mercy killing while others would label it murder. Yet Adler acknowledges that we do have knowledge of very general fundamental questions of action and behaviour which involve only the most universal principles, however other than these basic standards, all other questions can only be answered by opinions.

|

| Between Art and Nature (1888) Pierre Puvis de Chavannes source Wikiart |

Opinion and the Need for Freedom

On all detailed practical matters men can have different opinions and reasonably disagree, however this fact leads to two practical consequences. The first is human freedom, and the second the need for authority. At first glance, these two consequences appear to contradict each other. Adler examines both in an attempt at reconciliation.

Our judgement with regard to human freedom — in that we decide to adopt a means of behaving or not, to follow a particular course of action or not, etc. — although it is based on opinion is one source of human freedom, yet not the only one. There are three levels of explanation for this distinct freedom:

- When we act voluntarily and are not manipulated or impelled by others about our judgement of what to do, we act using free will, carrying out our own judgements.

- With regard to practical judgements, we use our opinions about right and wrong to carry out our decisions. In both cases, we are not compelled by anything to make up our own minds. We are free to decide. We use practical judgements as to what to do and call it having free will. But if the Latin was literally translated, “free will” would be “free judgement”, librium arbitrium. In actuality, our action is “double free”: from the fact we have free opinions, we have free judgements which spur us to action.

- Now let’s suppose the opposite, and construct a case that is rather contrary to what we have been discussing: what if it was possible to know with complete certainty what was right and wrong is every case? Our actions would still be free but our judgements would not be free. Adler uses a story where he and a colleague argued about democracy, the colleague advocating for it and Adler not convinced that it was the best form of government. However, with study, Adler was brought over to his colleague’s point of view and wrote a paper supporting it, as a mathematician supports a conclusion. Was his colleague happy that he was in agreement? Absolutely not! He felt the very fact that Adler could demonstrate that democracy was the best form of government, went against the very tenets of it, in that it did not allow men to be free in their own conclusions. It took away their free choice. Interestingly, Adler states that he does not agree with his colleague and that his conclusion is actually knowledge and not opinion, yet it does not take away from human freedom at all, as his conclusion remains a general principle.

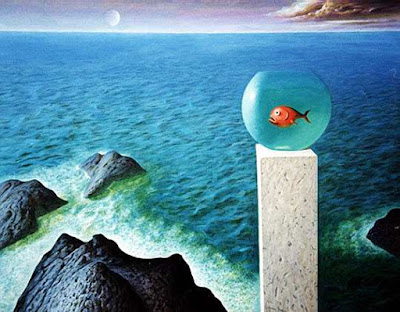

|

| Freedom in the Aquarium Sabin Balasa source Wikipedia |

Opinion and the Need for Authority

Adler now examines the second consequence of our practical judgements being matters of opinion. Men cannot live in society in peace and harmony unless there are common rules to govern their actions to which they all can agree and assent. Usually there is some authority which binds these rules over all. Now Adler says that opinion over action is not only a source of our need for authority, it is the source. To explain, human opinions can differ and men can reasonably disagree about matters of action, but ……. if you are going to live in society and all work towards a common goal, you must resolve your differences and find some way of agreeing. How can this agreement be attained? Not by reasoning because then you would have a matter of knowledge, not opinion. Adler knows of only two answers:

- The issue will be decided by superior force exercising compulsion over those of inferior strength.

- The issue is resolved by some higher authority which both are willing to accept.

Luckman asks Adler that if force is an alternative to authority, why should authority even be considered? Adler emphasizes that it is important that people submit to an authority that they are willing to accept rather than be compelled to obey, for only under the former do we remain free.

Luckman is still confused so Adler summarizes what he has already stated. When I personally read over his viewpoint, I think it is easy to disagree with Adler because his argument sounds so factual. In reality, because he is addressing opinion, right there we have a muddying of the waters. If we were examining knowledge, our viewpoints could be much more precise, but because we’re dealing with opinion, already we have to compromise on how we view it and therefore what the best means are of dealing with many situations. Adler is not prescribing the perfect mediums for a society that must function mostly on opinions, he is advising the best way given imperfect circumstances. Seen from this perspective, I can appreciate his argument.

|

| Raising Freedom (1974) Joanne Shaw source ArtUK |

Adler concludes by saying:

“What we have learned today is that opinion in regard to action is both one source of human freedom and also the source of our need for authority. And I hope what we can learn next time is how the principle of majority rule makes authority quite compatible with freedom in society. In the course of doing that, we cannot help but face the conflict between the majority and the minority opinions, and with that the problem of controversy about the fundamental social issues of any society at any time.”

The next essay is titled Opinion and Majority Rule.

The Great Ideas ~ The Difference Between Knowledge and Opinion

The Difference Between Knowledge and Opinion

When considering the distinction between knowledge and opinion there are some questions that need investigation:

- What sort of objects are the objects of knowledge, as opposed to the objects about which we can only have opinion?

- What is the psychological difference between knowing and opining as acts of the mind?

- Can we have knowledge and opinion about one and the same thing?

- What is the scope of knowledge? How much knowledge do we really have as opposed to the kinds of things about which we can only have opinions? What is the limit or scope of opinion in the things of our mind?

Luckman begs another question to Adler: Does freedom of conscience give a person a right to his own opinion in matters of religion and, if so, are matters of religious belief and religious faith simply matters of opinion rather than knowledge? Adler responds that this question is contained in the fourth question, as we try to separate the “sphere” of knowledge from the “sphere” of opinion.

Before he begins, Adler investigates the difference between knowledge and “right opinion”. With knowledge, you have the truth and know that it is true. With right opinion, you have the truth but you will not understand why it is true.

|

| Public Opinion George Bernard O’Neill source ArtUK |

It’s Better To Be Ignorant Than Wrong

Adler introduces the terms error and ignorance. In both cases, the person will not have the truth; then how is each term different? The person in error does not have the truth but does not know that he does not know the truth and, in fact, might think that he has it; whereas the person in ignorance does not have the truth and knows that he does not have it. Knowledge and right opnion (on the side of truth) are mirror images to ignorance and error (on the side of lack of truth).

Therefore, ignorance is closer to knowledge than error. In fact, to impart knowledge, one must first correct error to get the person in a state of ignorance so they can then begin to learn. This method was Socrates’ principle of teaching. He would go around “cross-examining the pretenders to knowledge and wisdom,” and by this method demonstrate their errors.

|

| Virtue and Nobility Putting Ignorance to Flight (c. 1743) Giovanni Battista Tiepolo source ArtUK |

School Children Mainly Learn Opinions

Ooo hoo! This should be a good one!

The Greeks were very concerned about the difference between knowledge and opinion. Plato believed that only knowledge is teachable; right opinion was not teachable because it was not established on reason, and since it had no principles, there was no basis for anything to be demonstrated.

Most of the subjects that children learn in school are right opnion, such as history, geography, etc., compared to geometry which can be rationally taught and learned, and outcomes can be proven based on principles.

Aristotle, however, felt that one man can opine that which the other man knows, one possessing right opinion and the other knowledge about the same thing. For example, a teacher teaching geometry knows the truth of the Pythagorean Theorem because he has seen the conclusion demonstrated but a student who can only say that it’s true because his teacher said so, only has right opinion of it on the authority of the teacher.

Anyone who argues from authority, holding an opinion or position, he is holding it as a matter of opinion. (Hold on to your hats for this next quote:)

“And whenever a teacher appeals to his authority to persuade the students to believe something, that teacher isn’t teaching; he’s really only indoctrinating them; he is forming right opinions in their minds.”

Luckman wonders how much, if any knowledge is taught in schools and if it’s even possible to attain knowledge in these institutions. Alder, while acknowledging that it’s a difficult question, promises to address it by dividing the domain of knowledge from that of opinion.

|

| A School Teacher Explains (1516) Hans Holbein the Younger source Wikiart |

Opinions Are Accepted Voluntarily

How do we determine the difference between the act of knowing and that of opining? When our compliance is involuntary, caused by the object about which we’re thinking, is knowledge; for example, if someone holds up two apples and then another two apples you are compelled to acknowledge that 2+2=4. An opinion leaves you free to make up your mind based on authority, your interests, your emotions, your passions, etc. Your opinion is an act of will, which Adler calls wishful thinking, and the emotional content is great; with lack of evidence of facts, one tends to support our opinions with emotions. Adler states schools may teach opinions but they must be substantiated and tested without merely relying on authority or knowledge. Luckman wants to know of what is taught in school, how much is knowledge and how much is highly probably opinion.

Adler responds to Luckman’s question, asserting that there are two answers, one given by the skeptic and the other given by the opponent to the skeptic. The skeptic believes that we have almost no knowledge, the opponent that we have substantially more knowledge.

The Skeptic

Michel Montaigne represent an extreme of skepticism, stating that everything is a matter of opinion and that man knows nothing. The illusions of the senses cause us to think we know when in fact, “… we mustn’t be fooled by the feelings which we sometimes have of certainty.” David Hume exhibits a more moderate skepticism, stating that we do have some knowledge, but it is knowledge based on science and mathematics. Hume believes that this is the only knowledge of which we’re in possession. Hume’s famous statement sums up his beliefs:

“If we take in our hand any volume ….. let us ask ‘Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number?’, that is, is it a work in mathematics? Or let us ask, ‘Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matters of fact and existence?’, that is, is it a work in experimental science? If the answer to both these questions is no, Hume says, ‘Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.”

In modern times, we have descended even further into scepticism than Hume. We question if even mathematics is knowledge based on Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry.

|

| Life’s Illusions (1849) George Frederick Watts source Wikiart |

(ooo, this is good)

Adler first looks at perceptual illusion. How do we know that there are illusions? We can only know something as an illusion if “we regard some sense perceptions as accurate,” otherwise we couldn’t categorize others as illusions. If there are two lines on a paper that look different lengths, but we pick up a ruler and measure each finding that they are the same, we correct an illusory perception. But if one sees the measurement itself as a perception and not as knowledge, one couldn’t have called the wrong perception an illusion.

With regard to mathematics, the opponent could say that “mathematics is not based only on assumptions but upon axioms, self-evident truths,” as are metaphysics and other branches of philosophical science.

History and experimental science likely fall under the label of highly probable opinion, so perhaps in this case the skeptic and his opponent are in agreement, however experimental science is a type of conditional knowledge, “conditional upon the state of the evidence at a given time.”

One last reply to the skeptic is given, Adler pointing out that even if the extreme skeptic tried to defend his case, he would defeat himself every time because he could not make an argument that did not establish something as knowledge.

|

| Religio and Fides (Religion and Faith) [1575-77] Paolo Vernese source Wikart |

Luckman still would like Adler to address if religion and matters of faith are knowledge or opinion. Adler says there are two views of religious faith:

- William James asserted that “religious faith is an act of the will to believe and this act of the will to believe takes place when we are beyond the evidence or the evidence is insufficient.” James believed that faith was strictly opinion.

- Thomas Aquinas believed, as James, that faith is an act of will, but unlike James, believed it is an act of will motivated by “the supernatural gift of the grace of God.” For Aquinas, faith wasn’t knowledge or opinion but somewhere in between.

To expand, Adler quotes Aquinas:

“The intellect assents to a thing in two ways: first, through being moved to assent by its very object which is known either by itself as in the case of first principles or axioms or through something else already known as in the case of demonstrating conclusions. In either case, you have knowledge, not opinion. Secondly, the intellect assents to something not through being sufficiently moved to assent by its proper object, but through an act of choice, whereby it voluntarily turns to one side rather than the other.”

If doubt or fear accompany the experience, you have opinion, but if certainly follows, one has faith. Aquinas continues: “And this certainty of faith, results from the fact that it is supernatural,” this gift from God, “since man, by assenting to maters of faith, is raised above his nature, this must needs accrue to him for some supernatural principle, moving him inwardly, and this is God. Therefore faith, as regard to the assent which is the chief act of faith, is from God, moving man inwardly by grace.”

Luckman doesn’t see how Aquinas has proven faith is intermediary, between both knowledge and opinion, rather like both of them, and Adler expands. Faith is like opinion because it is an act of will (“Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” Hebrews 11:1 NKJV), but it is also knowledge, in that there is a certainty that is even greater than the certainty of ordinary knowledge, but this certainty is based on the supernatural gift of grace.

Next Adler will investigate the problems of opinion in relation to human freedom in Opinion and Human Freedom.

⇐ How To Think About Opinion Opinion and Human Freedom ⇒

The Great Ideas ~ How To Think About Opinion

How To Think About Opinion

This section is presented as a conversation between Adler and Lloyd Luckman. I’m not certain who Mr. Luckman is but he appears to be Adler’s co-host and interviewer for the TV show. Luckman is confused as to why Adler would consider “opinion” a great idea. Adler explains.

He addresses both the theoretical significance and the practical significance of opinion.

The greatest problem in determining certainty and probability is the distinction between knowledge and opinion, therefore to judge the worth of opinions, people created the theory of probability. For a sceptic, we know nothing for certain and everything is a matter of opinion. One opinion is just as good as another and everything is subjective and relative.

Opinion is also connected with the great theoretical problem of agreement and disagreement. We essentially agree and disagree on every fundamental question.

“Controversy” has almost become a bad word but discussion and public debate are crucial to the health of a society. We have a moral duty to be hospitable to controversy.

Majority rule is essential in a democracy, but we also need to respect what is sound in the judgement of the minority.

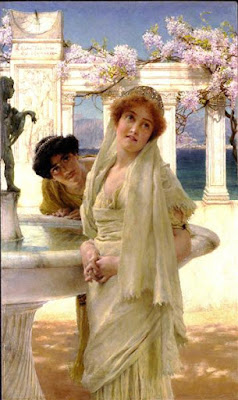

|

| A Difference of Opinion (1896) Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema source Wikiart |

Characteristics of Opinion as Contrasted with Knowledge

It is important to see the difference of both in terms of truth, but there is a definition of truth that must be agreed upon, and he proposes the following: “A statement is true if it says that that which is is, or if it says that which is not is not; and a statement is false if it says that that which is not is, or that which is is not.”

Opinion versus Knowledge

Knowledge is having the truth and knowing that you have it. Opinion consists in not being sure that you have the truth or not being sure what you say is true or false. For example, in a courtroom there is an opinion rule where the witness must state what he saw happen, not what he thinks happened. Opinions can be right or wrong, true or false. Knowledge cannot be false.

Another criteria for judging on knowledge or opinion is whether something is universally known or agreed upon. If everyone MUST agree, it isn’t opinion, it’s knowledge.

Additional criteria:

- Doubt and belief are relative only to opinion, never to knowledge. For example, “two plus two equals four” is known. As to whether there will be another world war or not, one can only offer an opinion.

A Right To Our Own Opinion

- There is no conflict with knowledge but there can be conflicting opinions. Reasonable men can agree to disagree.

- We can talk about a consensus of opinion, but we never refer to a consensus of knowledge. Aristotle’s rule for consensus of opinion is: “In arguments dealing with matters of opinion, we should base our reasoning on the opinions held by all. Or if not by all, at least those held by most men. Or if not by most men, at least by their wives. And in the last case, if we are basing it on the wives, then we should try to base our opinion or arguments on the opinions held by all the wives or if not by all the wives then by the most expert among them or at least by the most famous.” Rarely is there unanimity in consensus of opinion.

|

| Aristotle PaoloVeronese source Wikiart |

Questions, questions and more questions !!!

About what sort of things can we have knowledge, and about what sort of things can we only form opinions? Plato believed that it was only possible to have knowledge about those things that were fixed, permanent or eternal, but Aristotle disagreed, holding that it was possible to have knowledge of both the physical world and eternal ideas.

What is the psychological difference between knowing and opinion?

Can we have knowledge and opinion about the same thing? Or is it possible for someone to have knowledge about something, about which another person has only an opinion?

How much knowledge do we have? To what degree are the things that we deem to know really things we know or only things that we opine?

Socrates said that only God knows and for the most part, men have nothing better than opinion. To know this is wisdom. He was being rather ironic and intended to go on with the inquiry, which Adler plans to do in the next section where he examines in greater depth the difference between knowledge and opinion.

|

| A Difference of Opinion as to a Treaty Herman Frederik Carel Ten Kate source ArtUK |

⇐ How To Think About Truth The Difference Between Knowledge and Opinion ⇒

The Great Ideas ~ How To Think About Truth

How To Think About Truth

Heavens, start with a light one, why don’t you, Adler! And it honestly wasn’t a long essay at all but it was dense. Dense, as in tons of relevant information packed into a small space. Dense, as in my brain hurts. Let’s see if I can untangle some neurons and launch into a coherent explanation.

|

| Truth Stolen Away by Time Beyond the Reach of Envy and Dischord Nicolas Poussin source Wikiart |

Truth is associated with the pursuit of knowledge which encompasses all earnest endeavours or investigations. False knowledge does not exist, therefore, what you have in your mind about the object you are trying to know is “knowing the truth”.

However, there are problems with the pursuit of truth and Adler summarizes them:

Scepticism – the sceptic either believes that nothing is true or false, or that everything is equally true or false. We are unable to distinguish or know true or false, have knowledge, or possess truth. Freud spoke against sceptics, saying, “If it were really a matter of indifference what we believe, then we might just as well build our bridges of cardboard as of stone, or inject a tenth of a gram of morphine into a patient instead of a hundredth, or take teargas as a narcotic instead of ether; but the intellectual anarchists themselves (the sceptics) would strongly repudiate any such practical applications of their theory.”

Relativism – Relativists believe that what can be true for one person, can be false for another and vice versa, or what was true in one point in history may not be true in others. The opposite view to relativism is that truth is “absolute and immutable, the same for men everywhere.”

Pragmatism – Pragmatists believe truth is only truth if it bears fruit in action — it is only truth if it works. The opposite view to pragmatism is that practical verification is unnecessary for man to have an awareness of truth.

Adler splits the problem into smaller pieces, now asking not only “what is truth,” but “what is true?”

|

| Philosophy Unveiling Truth Louis Jean François Lagrenée source ArtUK |

Truth Defined

The easier question of the two is: What is Truth?

Within oneself, one knows the difference between the truth and a lie. There is a correspondence between our own words, speech and thoughts. Between two people, using words, we develop a truth of communication or a truth of understanding between each other. However the third case is more problematic: finding truth within reality ….

The Easy Problem of Truth

The generally agreed upon definition of truth in European thought is the “correspondence between the mind and reality.” From the ancient to the Medieval to the modern world this definition holds true.

Plato: A false proposition is one which asserts the nonexistence of things which are or the existence of things which are not.

Aristotle: To say of what is that it is or of what is not that it is not, is to speak the truth or to think truly; just as it is false to say of what is that it is not or of what it is not that it is.

Aquinas said that truth in the human mind consists in the mind’s conformity to reality (that which is)

John Locke: Though our words signify nothing but our ideas, yet being designed by them to signify things, the truth they contain will be only verbal when they stand for ideas in the mind that do not agree with the reality of things.

William James was a pragmastist who maintained that the successful working of an idea signaled truth, meaning the truth of our ideas have an agreement with reality.

However, this definition is only the starting point and many problems remain. It is more difficult to tell how something is true or false.

As mentioned above, it is relatively easy for the mind to directly correspond with its own thoughts or indirectly with the thoughts of others. This brings us to our very difficult case.

The Difficult Problem of Truth

How does one test the correspondence with my own mind with that of reality?

We express our thoughts in statements or propositions; reality is the facts about which we’re trying to make the propositions. The problem? It is impossible for us to grasp the facts except within our own propositions, therefore we have no direct way of discerning whether the propositions correspond to the way things are. Likewise, we have no indirect way of discerning either, because we cannot ask reality questions and reality cannot answer back. We cannot have correspondence between what we know and what we are trying to know.

|

| The Endearing Truth (1966) Rene Magritte source Wikiart |

Consistency Is Needed For Truth

Some say a test of truth is noncontradiction. For example, the propositions a is b and a is not b cannot both be true; one must be true and one must be false. Consistency, coherence or absence of contradiction is a sign of truth for if reality were full of contradictions, then the presence of contradictions in the mind would not be a sign of falsity. Descartes propounded the idea that when our ideas are clear and distinct and contain no contradictions, then we know truth. Likewise, Spinoza said, “What can be more clearer or certain than a true idea as the standard of truth? Just as light reveals both itself and the darkness, so truth is the standard of itself and of the thoughts.”

Yet Adler does not think this explanation sufficient, for, of the two propositions, how are we to know which is true? We can only discover truth if we have some measurement or standard with which to measure these propositions. Aristotle said, “The human mind uses two kinds of principles. There are the unquestionable truths of the understanding which are axioms or self-evident truths and there are truths of perception, truths which we know, which we possess, when we perceive matters of fact, such as, ‘Here is a piece of paper in my hand,’ or ‘Here is a book, I see a book, I observe a book.'” If we can test the truth of our propositions against these self-evident truths, we begin to solve the problem.

The Immutability of Truth

Many people can change their minds, but this has nothing to do with a change in truth or what is true. If the earth is round, it is round no matter how many people claimed that it was flat. It’s fair to say that true is immutable, but human beings do not possess truth immutably.

|

| Truth presenting a Mirror to the Vanities of the World Northern European School source ArtUK |

Oh heavens, I can already tell that this project is going to take much more effort than I expected. It’s truly an introduction to philosophy. I just have to keep telling myself that it will be worth it …….