“My father had a small Estate in Nottinghamshire; I was the Third of five Sons.”

As Samuel Johnson stated, Gulliver’s Travels is a work “so new and strange, that it filled the reader with a mingled emotion of merriment and amazement.” One must remember that at the time of Gulliver’s Travels, readers had rarely encountered prose fiction in the form of stories, let along the fantastical stories and adventures of Gulliver. They didn’t quite know how to respond.

In the last chapter of the this book, its purpose is laid out to the reader, that Swift’s “principal Design was to inform, and not amuse thee.”, a deviation in form, since most medieval writers sought to do both. The Roman lyric poet, Horace, stated that, “The poet who pleases everyone is the one who blends the useful with the sweet, simultaneously amusing and informing the reader.” Likewise, Thomas More in his Utopia states that his book is “A Truly Golden Handbook, No Less Beneficial than Entertaining”; Shakespeare seeks also to entertain and instruct, and The Cantebury Tales are described as “tales of best sentence and sola”, expressing the standard medieval definition of literature which both informs and gives pleasure. So why does Swift no longer want to amuse readers? Why does he choose to change the medieval model of how literature was represented? If his readers have not noticed the festering undercurrents of judgement within the story, it’s as if Swift was determined emphasis the seriousness of the work. As throughout his story, he gives the English people strengths that do not exist, so he also gives the reader amusement, where amusement does not exist. No wonder people were puzzled by his unique representation.

Born in Dublin in 1667, Swift spent the early years of his life moving between his hometown and London, attempting to gain a footing both in politics and the Church. His first position was with Sir William Temple a retired English diplomat who was writing his memoirs. Swift formed a close relationship with Temple and when he died, Swift hoped to gain a position at Canterbury or Westminister through King William, but the position never materialized. Amid various other disappointments, Swift continued his travels between Ireland and England, and during these years, he produced A Tale in a Tub and The Battle of the Books, gaining a reputation as a writer. Gulliver’s Travels was published later in his career, in 1726.

|

Mural depicting Gulliver surrounded by

the citizens of Lilliput

source Wikipedia |

Episodic in nature, Gulliver’s Travels follows Lemuel Gulliver as he visits various unknown civilizations and learns their ways while gently comparing their societies with those of his own. I say gently because Gulliver makes his musings appear as a gentle examination, but Swift has other ideas. One doesn’t have to look very hard to see that this work is a sweeping condemnation of the human race.

Gulliver first lands in Lilliput where the society is diminutive in stature compared to Gulliver’s enormity. Initially accepted by the Lilliputians because of his good behaviour, he eventually upsets them by refusing to help them conquer another province and he is forced to escape.

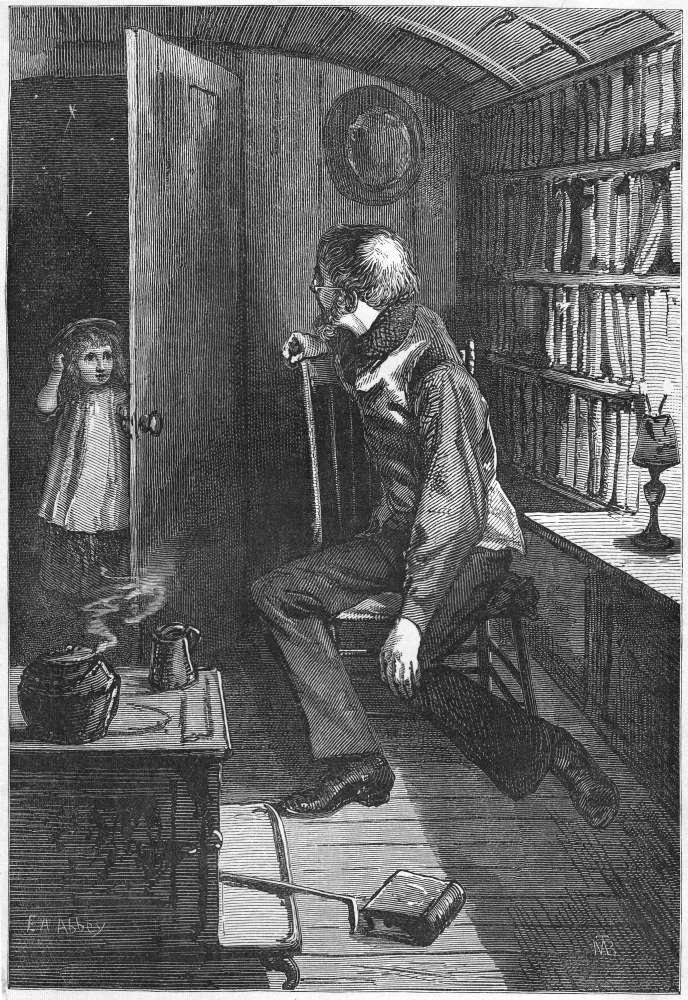

|

Gulliver exhibited to the Brobdingnag

Farmer – Richard Redgrave

source Wikipedia |

His second adventure is nearly an inversion of the first, in that this time Gulliver is small and, landing in Brobdingnag, soon realizes the gigantic features of its inhabitants. While being poorly treated by his first family, Gulliver eventually comes to the Queen who treats him reasonably well and he is able to converse with the King. The King, however, becomes unhappy with his description of the state of Europe, in particular their use of guns and cannons.

|

Gulliver discovers Laputa,

the flying island

J.J. Granville

source Wikipedia |

The next adventure includes the flying island of Laputa, which is a rather bizarre place. The inhabitants are devotees of the arts of mathematics and music only, but not only fail to employ them for any benefit to society, they also, through self-deception, are blindly unable to recognize their failures.

The land of the Houyhnhnms is Gulliver’s fourth and final stop, a land of wise and noble horses, but he also encounters a race called Yahoos, a race very much like himself yet more filthy, vulgar, bestial and stupid. Although they at first recognize him as a Yahoo, the Houyhnhnms finally take to Gulliver, impressed with his cleanliness and ability to reason. Yet in spite of the relational ties he makes in this land and his desire to remain among these highly civilized beasts, the horses foresee a danger in Gulliver’s presence and send him off in a boat. When he arrive home, our protagonist is a changed man. Disgusted with the “Yahoos” of his country, he is barely able to live in their company, finally choosing a rather secluded life.

|

Gulliver taking final leave of

the Houyhnhnms (1769)

Sawrey Gilpin

source Wikipedia |

Through Gulliver’s interaction with the Liliputans and the Brobdingnagans, Swift satirizes British politics. The Liliputans are only concerned with petty and trivial problems, and in their self-aggrandization can only see themselves as governors of the whole world. Yet while Liliput represents a small view of man, Brobdingnag represents a large one. As in Liliput, Swift explores the contrasts between liberty and law, but now the situation is reversed as Gulliver is in miniature in a land of giants. The island of Laputa is built upon philosophy and it’s inhabitants are seen as Swift’s critque of scientism, or that the only way to true knowledge is through scientific disciplines. Only what can be seen and measured is taken into account, but, of course, this leaves no room to examine the soul. The land of the Houyhnhnms is perhaps the most fascinating part of the voyages. In this land the beasts are the civilized society and the Yahoos, who are human, are savages. The Houyhnhnms live by reason and that reason, working within nature, give rise to their idyllic existence. Gulliver believes that if he lives long enough with his friends, this virtue will rub off on him, but in fact the horses see his reason as imperfect and therefore he is more dangerous than a Yahoo who has no reason at all. In reality, Gulliver is half-way between both species, halfway between pure passion and pure reason.

Apparently both Sir Walter Scott and William Thackeray were shocked and repulsed by Gulliver’s fourth voyage, yet there is still argument as to whether Swift’s work was a satire in the form of Horace, where he is only lightly satirizing Gulliver’s idealism, or the heavier satire of Juvenal, whereupon his writing is a vitriolic, sarcastic diatribe condemning the human race. I’ll leave it to the reader to decide. Yet perhaps Swift himself can shed light on his intentions:

“I have ever hated all Nations professions and Communityes and all my love is towards individualls for instance I hate the tribe of Lawyers, but I love Councellor such a one, and Judge such a one for so with Physicians (I will not speak of my own trade) Soldiers, English, Scotch, French; and the rest but principally I hate and detest that animal called man, although I hartily love John, Peter, Thomas and so forth. This is the system upon which I have governed myself for many years (but do not tell) and so I shall go on until I have done with them I have got materials toward a treatise, proving the falsity of that definition animal rationale [rational animal], and to show it would be only rationis capax [capable of reason]. Upon this great foundation of Misanthropy (though not in Timon’s manner) The whole building of my Travells is erected. And I will never have peace of mind until all honest men are of my Opinion.”

While I thought Swift’s satire brilliant, and his characterizations mostly just, I felt that he focused only on the negative aspects of human nature. If Swift really saw the world only through a lense of disappointment, treachery, selfishness, and deceit, yet missed the integrity, loyalty, virtues and goodwill of the flip-side of human nature, that is truly a tragedy.

Read for my Classics Club Spin #8, Fariba from Exploring Classics joined me in reading this one. Here is her most excellent review. Thanks for the company, Fariba!

_by_Francis_Grose.jpg)

_-_St_Macarius_of_Ghent_Giving_Aid_to_the_Plague_Victims_-_WGA16655.jpg)

_edited.jpg)