“I am Cheap Jack, and my own father’s name was Willum Marigold.”

And so we are introduced to Doctor Marigold, bestowed with such an unusual first name for a Cheap Jack in honour of the doctor who delivered him. I did not imagine him in the appearance of the rather dandified peasant-gypsy looking gentleman on the cover to the left, but I suppose that’s beside the point. In any case, Doctor Marigold, as you know, is a Cheap Jack. For those who don’t know what a Cheap Jack is (I raise my hand), it’s a hawker who deals in bargain merchandise, anything from plates to frying pans to razors to watches to rolling pins and everything in between. Marigold has followed his father’s trade like a good son.

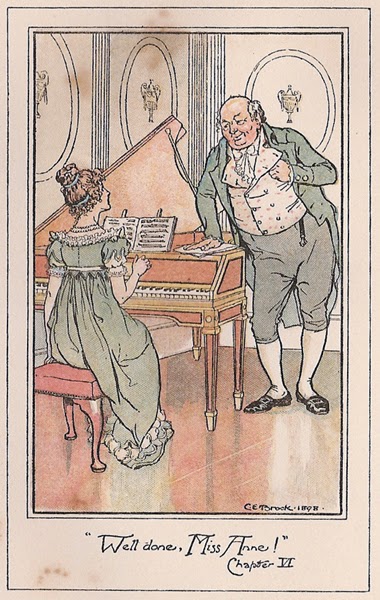

|

| Doctor Marigold 1868 E.G. Dalziel source Victoria Web |

Soon Marigold marries a woman who is not a bad wife by his estimation, but whoa, does she have a temper! She berates and torments her husband, and later beats their daughter, Sophy, while Marigold stands and watches. Why doesn’t he intervene? Because it causes more of a ruckus than observing, and then people suspect that he is beating his wife. Wimp.

Sophy grows up especially attached to her father and fearful of her mother — no kidding. Yet with their vagrant lifestyle, she becomes ill and passes away. One fateful day, the now childless couple come across a mother beating her tearfully pleading daughter, and with a shrill scream his wife tears away and drowns herself in the river. Good riddance.

Lonely Marigold now roams the country alone, until one day he comes across a deaf and dumb child whom he purchases and calls Sophy. They are devoted to each other for years, until, when she reaches sixteen, he decides to have her educated and puts her in an institution for two years. When he returns she is thrilled to see him, but as they resume their lives, he learns that she has acquired a suitor. Old generous Marigold decides he cannot stand in the way of their love —- although Sophy is willing to give it up to stay with her father —- and allows them to marry. The couple then move to China and five or so years later return with Marigold’s granddaughter for a reunion.

|

| Grandfather E.A. Abbey source Victoria Web |

Again, Dickens is somewhat of a trial to read. On one hand, his stories engage you for being overly maudlin and nauseatingly sentimental but I can never shake the feeling that he seems to think that as long as he uses affected emotional scenes and obscurely clever sentences, he can win adherents with such contrived effort. I find it almost insulting. However, as much as the first part of the story really irritated me, I must admit, I somewhat fell for it in the end. Perhaps Dickens achieved his desired effect after all.

This short story, so far is my least favourite of my Deal Me In Challenges. We’ll see what next week brings.

Deal Me In Challenge #7 – Three of Clubs

_by_Francis_Grose.jpg)

_-_St_Macarius_of_Ghent_Giving_Aid_to_the_Plague_Victims_-_WGA16655.jpg)