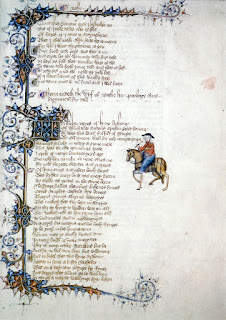

The Host becomes aware of the passage of time through various observations of nature and it causes him to reflect on what some great sages have had to say about lost time. He compels the Man of Law to relate his tale to discharge his duty. The Man assents, but then starts a long monologue referring to the manner in which Chaucer tells his stories, and giving him some acclaim, and then begins to tell of stories that are so foul, about which Chaucer would never write. However, there is some reference to a real character of the time, a Mr. John Gower, who would write about such offensive topics, such as incest, and one wonders if the author is chastizing this man or attempting to antagonize him into a response. In any case, the Man of Law claims his tale will not follow such abomination, and that he will relate it in prose.

|

| The Man of Law |

Well, even though the Man of Law claimed his plan was to chronicle his tale in prose, he recounts it in complex seven-line rhyme-royal stanzas. The prologue of the tale appears to begin almost as a lament against poverty, its detriments and adversities, but then the narrative merges into a commentary on the prosperity of wealthy men. The Man of Law tells of a merchant who told him the story which he will now recount.

The Man of Law’s Tale

The First Part:

Syrian merchants who were known for trading in excellent wares, took a journey to Rome and, while staying in that bustling city, learned of the renown of the beautiful, virtuous Lady Cunstance, the Emperor’s daughter.

Now, when the merchants returned from Rome, they brought news to the Sultan of Syria about the lovely Lady Cunstance, and the Sultan determined to have her for his own. Then there comes a kind of prophecy:

“Perhaps in that large book

Which men call the heaven was written

In stars, when he was born,

That he because of love should have his death, alas!

For in the stars, clearer than is glass,

Is written, God knows, whoever could read it,

The death of every man, without doubt.

In stars, many a winter before then,

Was written the death of Hector, Achilles,

Of Pompey, Julius, before they were born;

The strife of Thebes; and of Hercules,

Of Sampson, Turnus, and of Socrates

The death; but men’s wits are so dull

That no person can well interpret it fully.”

And in Middle English:

“Paraventure in thilke large book

Which that men clepe the hevene ywriten was

With sterres, whan that he his birthe took,

That he for love sholde han his deeth, allas!

For in the sterres, clerer than is glas,

Is writen, God woot, whoso koude it rede,

The deeth of every man, withouten drede.

In sterres, many a wynter therbiforn,

Was writen the deeth of Ector, Achilles,

Of Pompei, Julius, er they were born;

The strif of Thebes; and of Ercules,

Of Sampson, Turnus, and of Socrates

The deeth; but mennes wittes ben so dulle

That no wight kan wel rede it atte fulle.”

There is a problem, however. The Sultan is a Muslim, and Custance is a Christian, and what good Roman Christian would give his daughter to a Muslim? So the Sultan and all his vassalage, agree to convert, so he can take Cunstance in marriage.

|

The Silk Merchants

Edwin Lord Weeks

source Wikiart |

When it comes time for Lady Custance to depart for her new home and husband, she is filled with sadness and regret:

Alas, what wonder is it though she wept,

She who shall be sent to a foreign nation

From friends who so tenderly cared for her,

And to be bound under subjection

By one, (of whom) she knows not his character?

Husbands are all good, and have been for years;

Wives know that; I dare say you no more.

Allas, what wonder is it thogh she wepte,

That shal be sent to strange nacioun

Fro freendes that so tendrely hire kepte,

And to be bounden under subjeccioun

Of oon, she knoweth nat his condicioun?

Housbondes been alle goode, and han ben yoore;

That knowen wyves; I dar sey yow na moore.

Yet even though she dreads her fate, she will gladly go because of obedience to her parents and for her love of God. She claims though, that Mars has slain her marriage, which is interesting as Mars is the god of war. I wonder if this allusion will play into the story later on?

So while the Sultain awaits his bride, the Sultan’s mother is irate that her son is going to forsake his beliefs. She acquires the support of the council to pretend to accept Christianity before slaying all the Christians at the wedding banquet. The narrator compares the Sultaness with Satan, in her quest to destroy what is pure and virtuous.

|

The Sultan of Morocco (1845)

Eugene Delacroix

source Wikiart |

The Second Part:

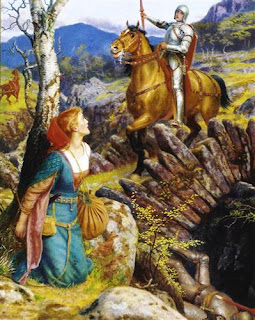

The Muslims massacre all the Christians, including both the ones from Rome, the Sultan, and those of his party who were planning to convert. However Lady Custance is left alive, to be set afloat on a ship, to survive with minimal provisions, if she is able. She is afloat for many years and we are told that God kept her alive to show his works in her, and so follows a list of historical people whom God has kept from harm. Finally, she is tossed onto the coast of Northumberland near a castle and, disoriented and pitiful, is found by the constable of the castle, who takes her to his wife, Hermengild.

Through Lady Custance’s prayers and sweet character, the good lady is converted in this land full of pagans, from where Christians had already fled, and hence, her husband also. But Satan, ever up to his mischief, makes a knight fall in love with Custance and want his way with her, but Cunstance guards her virtue and will not be swayed by his amorous advances. The knight, enraged at her resistance, kills Hermengild by slitting her throat and places the knife by the sleeping Cunstance. The constable and King Alla return and see the murdered woman. Everyone is shocked that the virtuous lady Cunstance could commit such a horrible deed yet the knight testifies against her, so what can be done? But lo, as he swears the truth on the Bible, a hand smites him on the neck and his eyes burst out of his head, while a voice is heard condemning the slander and praising Cunstance. Because of this miracle, many were saved, including the king, who married Cunstance and made her a queen.

This king’s mother too, is against the marriage to a “foreigner”. When the king is away and Custance is delivered of a son, through some macchinations, a letter is delivered to the king telling him his wife has delivered a monstrous infant and that no one wanted to go near the castle. The king, with his new Christian charity, claims that he will accept the child whether fair or foul. Again, the king’s mother, with her evil servant, Donegild, intercepts the king’s letter and instead, it is said that he banishes Cunstance from the kingdom. Custance accepts her fate, secure in her faith, but prays for protection for her innocent babe.

|

Young Mother With Child

Lucas Cranach the Elder

source Wikiart |

The Third Part:

When king Alla returns, he learns of the wretched deed done to his wife and son, and he has his mother slain for her troubles. But he is left to mourn for Cunstance, who sails for five years, reaches another heathen land, has her virtue once again targeted by a lecherous male, and is protected by God as the man falls into the sea and drowns. Finally, she is picked up by a Roman ship returning from a battle with the Syrians over the slaying of the Christians, and when she reaches Rome, she abides with a senator and his wife.

Now King Alla is remorseful for the slaying of his mother and decides to make a pilgrimage to Rome to receive his penance. He is befriended by the senator, first sees his child then his wife there, and is moved to tears of joy. Lady Cunstance is at first wary, as she remembers his treachery, but when the truth is known to her, she rejoices at their reunion. She makes peace with her father and returns to England, where she lives in bliss with her husband until he dies a year later. To Rome she then goes to live with her father happily, and her son, Maurice, eventually becomes a respected Emperor.

|

Bamburgh Castle, Northmberland (1874)

James Webb

source Wikiart |

I absolutely loved this story. Lady Cunstance is painted in saintly form, and I suppose that people could criticize that she’s too perfect. But I always believe that the purpose of these types of stories were to teach, and while Cunstance is “perfect,” there is often nothing but turmoil happening around her, so in these cases, the storytellers are instructing us in the right responses in times of trouble and strife, while also illustrating the benefits that can come from our right actions during these times. Conversely, they also can illustrate the outcomes of wrong actions and their consequences.

Yet, even amid Cunstance’s perfection, the life lessons are realistically presented:

“….. But little while it lasts, I you promise

Joy of this world, because time will not stand still;

From day to night it changes like the tide.

Who lived ever in such delight one day

That he was not moved by either conscience,

Or anger, or desire, or some kind of fear,

Envy, or pride, or passion, or offence? ……”

Middle English:

…..But litel while it lasteth, I yow heete,

Joye of this world, for tyme wol nat abyde;

Fro day to nyght it changeth as the tyde.

Who lyved euere in swich delit o day

That hym ne moeved outher conscience,

Or ire, or talent, or som kynnes affray,

Envye, or pride, or passion, or offence? …..

A few commentaries on this tale surmise that the Lady Cunstance symbolizes “crusading fever” (or perhaps it was fervour 😉 ) but I didn’t read that supposition into the tale at all. For me, the focus was on Cunstance, her virtue and her faithfulness to God no matter what her circumstances, and what comes out of that perseverance and faith. It is basically the story of a saint, and I believe Chaucer meant it to be so. But as for the narrator, that is a different story. In the General Prologue, the Man of Law was obviously an astute and respected character, yet there was some cunning and wiliness behind his demeanour. The story itself stands, but did he have another purpose for telling it?

|

The Forum, as seen from the Farnese Gardens, Rome (1826)

Camille Corot

source Wikiart |

Chaucer finishes the tale in a flourishing style:

And fare now well! my tale is at an end.

Now Jesus Christ, that of his might may send

Joy after woe, govern us in his grace,

keep us all that are in this place! Amen

Middle English:

” … And fareth now weel! my tale is at an ende.

Now Jhesu Crist, that of his myght may sende

Joye after wo, governe us in his grace,

And kepe us alle that been in this place! Amen

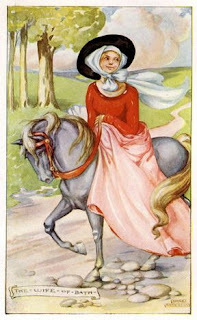

In the Epilogue, the Priest is called upon to tell the next tale, but the Shipman strongly protests saying that they all believe in God and that the sermonizing will only “sprinkle weeds in their clean grain”. He states that he will tell the next tale. This is puzzling, because in the order that we’re following, the next tale is The Wife of Bath’s Tale. I’m sorry, but I have no idea why.