“Miss Brooke had that kind of beauty which seems to be thrown into relief by poor dress.”

“Miss Brooke had that kind of beauty which seems to be thrown into relief by poor dress.”

I first read Middlemarch during the summer of 2014 and was mesmerized. The lives of the inhabitants were painted in detail and somehow came alive until I was part of the community and involved in all their celebrations and struggles. I finished it in three weeks and then longed to go back. Well, it’s been over ten years since my last read of it and with some more maturity and the input of others, I was curious as to how I would respond upon my second reading.

Written by Mary Ann Evans, who used the pen name, George Eliot, the novel is set in a fictional English town and follows the lives of a myriad of characters, painting their life stories from a detailed and sympathetic palette. The book spans the years of 1829 – 1832 which was a particularly turbulent time in British history, as it corresponds to the time of the Reform Act of 1832 and the years leading up to it. While the novel intersects with social reform, such as the advent of railroads, advances in medical science, and extending voting rights to a lower segment of the working-class population, Eliot does not really delve into the history but simple shows the reader how these changes played a part in village life and community.

There are two main stories which Eliot focuses on in the book; that of Dorothea Brooke and of the new doctor in Middlemarch, Tertius Lydgate.

Dorothea and her sister Celia live with their uncle, Mr. Brooke, who owns an estate and manages his tenant farmers. Immediately, the reader is introduced to Dorothea’s piety but also to her tempestuous spirit as she beats against the bonds of womanhood, wishing she could do something meaningful with her life by improving the estate and the lives of her uncle’s tenants. Frustration with her situation plagues her until she meets Mr. Casaubon, an elderly intellectual, whose unremitting theological work on a book of scholarly mythologies, captures her interest and she imagines herself helping this great man produce a masterpiece. To the horror of most of the village, she marries Casaubon, a man over 30 years her senior, and while she’d had hopes of an equal and supporting partnership, she soon learns her husband had only wishes for someone who would agree with his every thought and soothe his crotchety temperament. When the meeting of Casaubon’s nephew on their honeymoon, an artistic young man named Will Ladislaw, Dorothea encounters many emotions that had once been foreign to her, and a meeting of minds between the two of them fosters an unreasonable jealously from her husband. The conflict between duty and sentiment lead her on a journey which results are as much edifying as they are uncomfortable and unexpected.

Concurrently, Dr. Tertius Lydgate arrives in town, a new doctor with new methods and who is greeted with both great hope and great suspicion; Dr. Lydgate’s “new science” and new ideas as to the treatment of his patients are lauded by some, yet deprecated by others. Caught up in his work, marriage is not on the horizon until he meets the lovely Rosamund Vincy who is both fair and utterly selfish. Caught up in his feelings, Lydgate proposes marriage, little knowing that the career he has so devoted his life to will be entirely compromised by his marriage.

The reader is also introduced to Rosamund’s brother, Fred Vincy, who is completely captivated by Mary Garth, a childhood playmate and a young lady whose family is entirely beneath him. But the Garth family is made up of persistance, spirit and solid faith, and they will benefit Fred more than he could have ever benefited them.

Mr. Bulstrode, a spiritual landowner, had supported Lydgate in his quest to modernize medicine in the village, but a return of a person who was thought dead, brings up skeletons that he wished had remained buried, and his iniquitous response threatens his very respectability in the village.

One of my favourite parts of the novel is the end, where Eliot shows a special insight into not only the dreams of Dorothea, but the dreams of all of us if we use our lives well:

“Dorothea herself had no dreams of being praised above other women, feeling that there was always something better which she might have done, if she had only been better and known better …….

Certainly those determining acts of her life were not ideally beautiful. They were the mixed result of young and noble impulse struggling amidst the conditions of an imperfect social state, in which great feelings will often take the aspect of error, and great faith the aspect of illusion. For there is no creature whose inward being is so strong that it is not greatly determined by what lies outside it. A new Theresa will hardly have the opportunity of reforming a conventual life, any more than a new Antigone will spend her heroic piety in daring all for the sake of a brother’s burial: the medium in which their ardent deeds took shape is forever gone. But we insignificant people with our daily words and acts are preparing the lives of many Dorotheas, some of which may present a far sadder sacrifice than that of the Dorothea whose story we know.

Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

Eliot very skillfully weaves all the lives of her characters together in a charming tapestry filled with warmth of family, duty of position, responsibility in the community, sacrifices that everyone must make and the challenges that one faces in life.

And so, how did Middlemarch fare on my second reading ten years later? It was just as good. I was transported right back to the village and shared everyone’s hopes and struggles and successes as if it were yesterday. This time I was able to learn a little more about the Reform Act, which made me even more sensitive to the changes of time and habits that would have affected the villagers.

Mortimer J. Adler, the influential philosopher, educator and author of How To Read A Book, when speaking to Charles van Doren, said that Eliot’s work was a wonderful feat in creating a whole village but that the plot tends to clunk along. As much as I love Adler, for me, that just wasn’t true. Somehow Eliot managed to weave a magical tale and, in spite of literary glitches, manages to sweep up the reader and whisk them away with her prose into a world that, even with its remoteness, was somehow warm, recognizable and treasured.

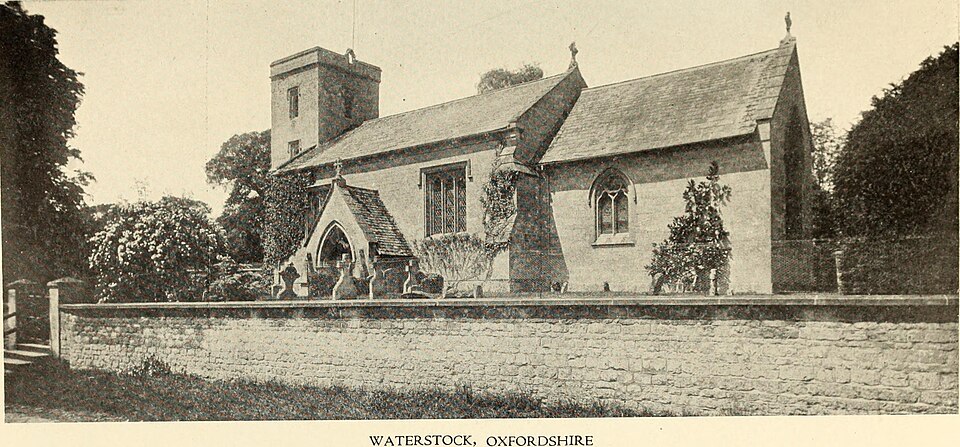

There was a wonderful BBC serial done of this novel, featuring Juliet Abrey and Rufus Sewell which I highly recommend. It was filmed in Stamford, Lincolnshire and many of the pictures I included in this post are from that village. A step back in time …..

Other Reviews of George Eliot novels:

The first time I read Middlemarch I read it as a romance about Dorothea. The second time I read it as a tragedy about Lydgate. But, of course, it’s both. Classics do change on you that way, don’t they?

Hi Reese, yes, it’s certainly both. Not to mention a coming-of-age for Fred (and Dorothea, of course), and a cautionary tale on marriage, and so many other things. It’s still high up there with my favourites!