“The one who saw the abyss I will make the land know;

of him who knew all, let me tell the whole story

………… in the same way …….

[as] the lord of wisdom, he who knew everything, Gilgamesh,

who saw things secret, opened the place hidden,

and carried back word of the time before the Flood —

he travelled the road, exhausted, in pain,

and cut his works into a stone tablet.”

Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. Two-thirds god and one-third man, he built the walls of Uruk, the palace Eanna, and is powerful and commanding. There is no king like him anywhere. Yet in spite of having many of the qualities that could make him an honoured king, Gilgamesh oppresses his people and they cry out for relief. The gods create a wild man, Enkidu is his name. They fight and become fast friends, relieving the people of Gilgamesh’s despotism. Many adventures they have together, and many discoveries they make. Together they behead Humbaba who lives in the cedar forest and they also manage to kill The Bull of Heaven. Yet one of them must pay for this transgression and Enkidu falls ill, dying even as he laments. A heart-torn Gilgamesh, determined to find Utnapishtim and find the secret of everlasting life, travels through a number of trials to his journey’s end. “Surely, Gilgamesh,” Utnapishtim tells him, “you can stay awake for just a week, if you are expecting to have eternal life.” But Gilgamesh fails the test. In spite of his near godly status, our hero cannot escape the mortality common to all men.

“My friend Enkidu, whom I loved so dear, who with me went through every danger, the goom of mortals overtook him.

Six days I wept for him and seven nights: I did not surrender his body for burial until a maggot dropped from his nostril. Then I was afraid that I, too, would die. I grew fearful of death, so I wandered the wild.

…. How can I keep silent? How can I stay quiet? My friend, whom I loved, has turned to clay. My friend Enkidu, whom I loved, has turned to clay. Shall I not be like him and also lie down, never to rise again, through all eternity?”

|

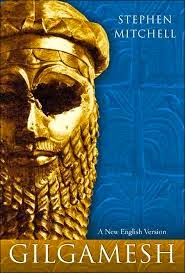

| Gilgamesh from the Chaldean account of Genesis source Wikipedia |

I found many paradoxes in this poem: Gilgamesh is a strong leader, yet he also abuses his power; Gilgamesh is two-thirds god, yet he is also doomed to die; Gilgamesh and Enkidu fight in order to bring peace to Uruk; women are portrayed as vehicles for pleasure, yet are also shown as being wise and having foresight; Enkidu is initially a wild-man, yet he is the one who “tames” Gilgamesh; and in spite of often not sleeping throughout most of the poem, Gilgamesh sleeps at the end, which prevents him from attaining immortality.

Yet in spite of the contradictions, the poet is clear that strength over reason is valueless. Gilgamesh learns that it is trust and integrity in the end that bring acclaim: valuing a friend’s life over his own, discovering the wisdom of accepting death as a part of life, and that being a true leader is about good character and responsibility to his subjects, rather than exercising tyranny, oppression and conquest over them.

And in spite of its ancient roots, the poem still resonates with us today. Here is a video of Captain Picard from Star Trek the Next Generation giving a short summary of Gilgamesh, in the episode “Darmok” (my favourite episode, BTW!) 🙂

About the translation: The Sîn-Leqi Unninni Gilgamesh story, found in the library of Ashurbanipal, is the most recent Akkadian version (circa 1200 BC), and is considered the “standard” version. The editors used it as their fragment of choice and because it contained a number of books that had only a few recoverable words, they had to resort to notes and the Old Babylonian version, in order for the reader to get the gist of the story. For my first read, in hindsight, I may have chosen a more fluid version, but this version was certainly adequate and scholarly enough that you got the full context of the poem.

Translated from the Sîn-Leqi Unninni version by John Gardiner and John Maier

I must admit it was through Star Trek that I first heard of this story! Literature in that style kind of intimidates me, but your review makes it sound worth the try. 🙂

It's not that difficult to read, but the breaks in the text doesn't give it consistent flow, so you have to try to ignore them.

Honestly, I'm reading The Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace now and I find it much harder to follow than Gilgamesh or most other intimidating classic literature that I've read. :-Z