Book VI (Erato)

“Thus Aristagoras met his end after inciting Ionia to revolt.”

Histiaios, the tyrant of Miletus arrives at Sardis after Darius released him in Susa and Artaphrenes inquired his opinion of the Ionian revolt. Loathsome worm that he is, Histiaios disavows any knowledge of the altercation and bats his eyes in innocence (well, not really, but you know what I mean). However Artaphrenes already knows his part and is not fooled by his duplicity. His response arouses fear in Histiaios: “Well, then let me tell you how and why it happened, Histiaios: you stitched up the shoe, and Aristagoras put it on.” In fear for his life, Histiaios escapes towards the coast, now an enemy of the Persians. Fleeing to Chios, Histiaios is taken in by the Chians which is a big mistake as he lies to them too about his part in the Ionian revolt, saying Darius wanted to uproot them to Phoenicia and vice versa. Still using underhanded tactics, he writes to Sardis urging revolt, but Artaphrenes intercepts the letters, so in a last ditch attempt, Histiaios begs the Chians to help restore him as tyrant of Miletus, however the people of Miletus do not want the return of his tyranny and repulse him. Still working his machinations, he seized ships sailing out of the Pontus.

Meanwhile, the Persian army and navy is approaching Miletus with help from the Phoenicians, Cilicians, Egyptians and the recently re-enslaved Cyprians. When the Ionian ships arrives at Miletus, the Persians are awed by the size of the fleet and get the Ionian tyrants to try to turn the Ionians traitors, but they disdainfully resist. A Phoceaean general named Dionysios is able to rally the undisciplined troops but soon their laziness overtakes them and as they engage the Persians, one group after another abandons the fight except for the Chians who perform great feats in battle in spite of their fleeing comrades. Dionysios, when he realizes what is happening, seizes three enemy ships and sails off to Phoenicia to become a pirate. Herodotus himself is “unable to record precisely which Ionians proved themselves to be cowards or brave and valiant men in this encounter, for now they all reproach one another.” Miletus is overcome by the Persians, their men killed and the women and children taken off to Susa as slaves. The Athenians were so upset at the city’s capture that when Phrynikos composed his play about its seizure, the audience wept and he was fined 1,000 drachmas for reminding them of this evil. And thus, there were no Milesians in Miletus and other Ionians left to form new colonies so as to not be subject to the Persians.

|

| Captive with rose (1943) Nicolas Roerich source Wikiart |

In Byzantium and hearing of the battle, Histiaios returns, falling on Chios with an army and capturing it before moving on to other areas. But the Persian general, Harpagos, is able to halt his advance, butchering most of his army and capturing Histiaios alive. Yet his reprieve does not last for long. Worried that Darius would pardon Histiaios if the man was given over to him, Harpagos and Artaphrenes, the governor of Sardis, decide to hang him from a stake and decapitate him, sending the head to Darius who is distressed and orders the head buried as Histiaios had been a benefactor to him.

Quite fascinating …….. as the Persians conquered islands, they would “net” people in that they would have a line of men that stretched from sea to sea and, holding hands, they would move forward, combing every inch of ground for people. The handsome boys they castrated and the virgins they sent to the king, burning the Ionians cities so the Ionians were subjugated to slavery for a third time, first by the Lydians and then twice by the Persians. The Phoenicians continued to sail towards Hellespont, conquering almost all the territory for the Persians as they went. Yet in spite of their merciless domination, the Persians brought laws and process to the Ionians, which promoted peace between peoples.

|

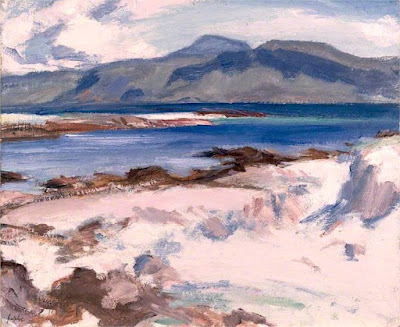

| Blue Sea, Iona (1927) Samuel Peploe source Wikiart |

King Darius dispatches his son-in-law, Madronios to depose the Ionian tyrants and form democracies before he moves on toward Athens, intending the same, but encounters resistance from the Thracian Byrgoi and after the navy’s wreck around Athos, they are forced to return to Asia.

The next year, crafty Darius tests if the Hellenes plan war against him by sending out heralds asking for earth and water (which signify subjection) from various cities in Hellas. They give what is asked by the Persians but the Athenians take umbrage at the Aeginetan’s gift and accuse them of conspiring against them. The Spartan king, Kleomenes, crosses over to Aegina, intending to arrest the guilty Aeginetans but Krios defies him. Meanwhile in Sparta, the lesser king, Demaratos, remains behind, proceeding to malign Kleomenes.

Thus, Herodotus launches into a lengthy digression about the Lacedaemonian lineage that produced two kings, which includes twin sons, yet one being honoured above the other. Still, Herodotus says the Hellenic story traces the lineage back to Perseus and the Greeks, however he believes before Perseus they must have been Egyptian by direct descent. Bascially, no one really knows. In war, he lists the privileges of the kings, in times of peace, and also the traditions practiced when the king dies. As to their professions, they inherit them from their fathers regardless of inclination or talent.

|

| Three Spartan Boys Practicing Archery (1812) Christoff Wilhelm Eckersberg source Wikimedia Commons |

Returning to Sparta, Kleomenes plots to rid himself of Demaratos by claiming that he is not the rightful son of Ariston, his father, as Ariston had taken his mother from his friend, and Demaratos’ birth was too soon after the marriage. Deposed of his kingship, Demaratos becomes a magristrate for the Persians but is insulted by Leotychidas who was part of the plot to disgrace him and is now king in his place. Demanding the story of his birth from his mother, she tells him he is either the son of Ariston, or the dead hero Astrabakos, who looked like Ariston but left her with garlands from his shrine as he visited her bedroom as a spirit. Happy with the answer, Demaratos escapes, pursued by the Lacedaemons but manages to reach the court of Darius where he is furnished with land and cities. Leotychidas, on the other hand, leads an army into Thessaly but is caught receiving a bribe, is exiled and dies in disgrace but that happens much later. At the moment, with the two kings against them, the Aeginetans surrender and Krios is taken as hostage along with nine other wealthy Aeginetans. Fearing Spartan justice, Kleomenes escapes to Thessaly and then Arcadia where he tries to stir up dissent against Sparta and eventually the Lacedaemonians bring him back to Sparta to rule, apparently thinking he would be less of a danger close by. But Kleomenes proceeds to go mad and his relatives have to confine him to a wooden pillory. Yet the king is craftier than all and, convincing a guard to give him a knife, he proceeds to multilate himself, beginning at his shins until he has disemboweled himself. Ugh! The Argives claim he went mad because of an oracle at Delphi predicting that he would capture Argos which did not come to fruition because of circumstances, but the Spartans say that he was addicted to strong drink because of the Scythians and that was the reason for his madness.

Thus the Aeginetans become incensed with the Athenian behaviour and the two wage war on each other, bringing other kingdoms into their dispute and most showing a stubborn implacability that brings about many deaths.

|

| Drawing of a Greek Vase depicting Darius I source Wikimedia Commons |

Meanwhile, Darius is planning to revenge himself on Athens for those who had previously refused to give him earth and water. Removing the unsuccessful Mardonios from command, he appoints the son of his brother Artaphrenes, Datis, as general who proceeds to sweep through kingdoms, starting with Naxos and making his way to Delos where he promises not to harm the site of the two gods or the people. After he makes a sacrifice and leaves, an earthquake thunders through Delos and Herodotus supposes it was a portent of evils that were to befall them:

“For in three successive generations, during the reigns of Darius son of Hystapes, Xerxes son of Darius, and Artaxerxes son of Xerxes, more evils befell Hellas than in all the other generations prior to that of Darius.”

In Greek, Darius means “Achiever,” “Xerxes,” Warlike, and Artaxerxes, “Extremely Warlike.”

|

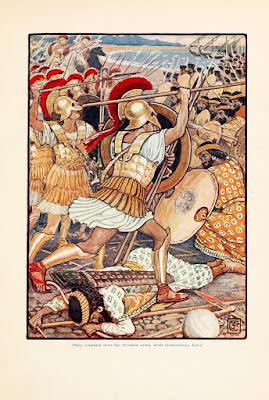

| The Battlefield at Marathon (c.1849) Carl Rottman source Wikimedia Commons |

The Persians conquer and burn Eretria, then depart for Athens, expecting full victory. Realizing the Persians are headed for Marathon, the Athenian general, Miltiades (son of Kimon and named after the Miltiades who settled the Chersonese) along with nine other generals send a message to Sparta by the runner Philippides asking for assistance against their foe. Philippides arrives in Sparta the day after he leaves Athens, assisted by the god, Pan. After a vote, the Athenians engage the Persians in battle, having spread their army as long as the Persians, but as they are fewer, are not as deep and the Persians begin to prevail in the middle, whereas the Athenians and Plataeans are succeeding in the wings whereupon they come together to fight the Persians in the centre. Meanwhile, the Persian fleet heads for Athens and is signaled by a shield from the shore. At the Battle of Marathon, 6,400 Persians die and 192 Athenians.

|

| source Wikimedia Commons |

The Spartans arrive in Athens too late for battle, travel to Marathon to view the dead Persians and then return home again. Back to the question of the shield signal, where the Alkmeonids are blamed, but Herodotus speaks of their hate of tyrants and cannot believe that they would commit such a treacherous act. He gives further history of the Alkmeonids, including a story of the judgement of the suitors, leading to the birth of Pericles.

After the Battle of Marathon, Miltiades gains even greater fame and convinces the Athenians to give him money and ships to lead against a country he will not reveal, to win great fortune. Given it, he sails for Paros but after besieging it for 26 days, he is thwarted by injuring his thigh and returns home in disgrace to be tried and fined, but eventually he dies from gangrene in his thigh.

Information on the conflict between the Athenians and Pelasgians follow, the Pelasgians finally carrying off Athenian women but find that the sons born of them are displaying an unusual unity between them, so they kill both the sons and wives, causing the ground to cease bearing crops and the women to cease bearing children. Ordered to offer reparation to Athens, the Pelasgians agree to the Athenian request for their land with a string attached: they will give it when a ship sails with the north wind and completes the journey from Athens to Lemnos in one day, knowing the task impossible. But one day in the future, Miltiades completes the journey in the indicated time and the Pelasgians have to give possession of Lemnos to the Athenians, although part has to be subjugated through battle.

⇐ Book V (Terpsichore) Book VII (Polymnia) ⇒

A++ You took great notes. Good for you.

Those Persians were relentless. No wonder they are regarded as great warriors. But one cannot overlook the impressive defensive of the Greeks, too. Nonetheless, the details are exhausting. Why do some men go to such extremes for power and control and revenge? What is the point or purpose?

P.S. I love that painting of the Battle at Marathon. I feel the same way about it.

Thanks ….. I'm still enjoying the posts but I will also be happy to begin Thucydides. I have a feeling there won't be the digressions from him and he will be more organized. We'll see ……

Sometimes they seem like children, so the invasions are reprisals and other times, they appear to just want something to do. A very different mindset from now, and it's hard to understand it.

It's getting harder and harder to find pictures for my posts. Wish me luck!!

I think I am going to attempt to answer Bauer's questions for history. I did this for Fanda's History challenge (she used Bauer's questions for analysis), and it was helpful and insightful.

That might be a good idea, especially for my final post for The Histories. After all this information in my book-by-book posts, what else is going to be left to say, LOL! 😉

Pingback: Herodotus' The Histories ~ Book V - Classical CarouselClassical Carousel

Pingback: Herodotus' The Histories ~ Book VII - Classical CarouselClassical Carousel