The oak one day says to the reed:

—You have a good right to blame the nature of things:

A wren for you is a heavy thing to bear.

The slightest wind which is likely

To wrinkle the face of the water

Compels you to bow your head—

While my brow, like Mount Caucasus,

Not satisfied with catching the rays of the sun,

Resists the effort of the tempest.

All for you is north wind, all seems to me soft breeze.

Still, if you had been born in the protection of the foliage

The surrounding of which I cover,

I would defend you from the storm.

But you come to be most often

On the wet edges of the kingdoms of the wind.

Nature seems to me quite unjust to you.

—Your compassion, answered the shrub,

Arises from a kind nature; but leave off this care.

The winds are less fearful to me than to you.

I bend and do not break. You have until now

Against their frightening blows

Stood up without bending your back;

But look out for what can be. —As the reed said these words,

From the edge of the horizon furiously comes to them

The most terrible of the progeny

Which the North has till then contained within it.

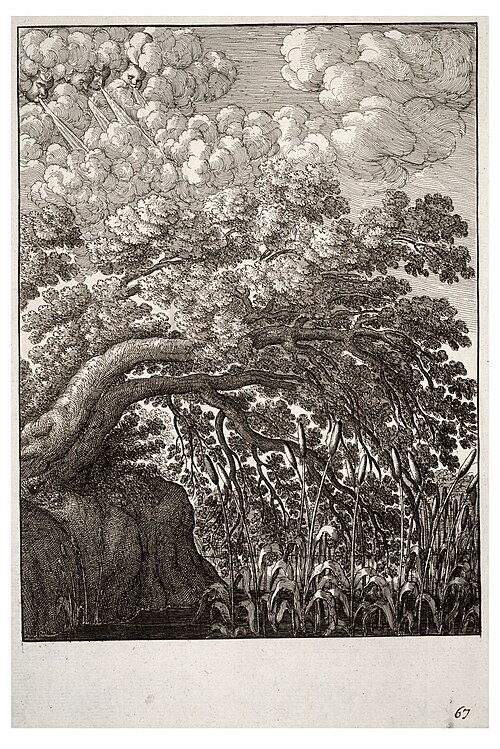

The tree holds up well; the reed bends.

The wind doubles its trying;

And does so well that it uproots

That, the head of which was neighbor to the sky,

And the feet of which touched the empire of the dead.

Alright, so this is a poem rather than a short story but interesting nonetheless. The story of The Oak and the Reed goes back as far as Aesop. The story’s early theme is concerned with pride and humility, giving rise to the proverbs, “better bend than break,” and “A reed before the wind lives on, while mighty oaks do fall.” of which the latter first appears in Troilus and Criseyde by Geoffrey Chaucer. There are also a number of other possible comparisons.

With de La Fontaine’s poem, we have concern coming from the oak at how the reed must struggle with the wind, but also compassion, as the oak claims if only the reed was within its foliage, it would protect him. The reed, responding, notes the oak’s kind nature but as it can bend, the wind is perhaps less of a concern to him. And thus, the wind attempts to beat against both and the oak loses its battle against the tempest.

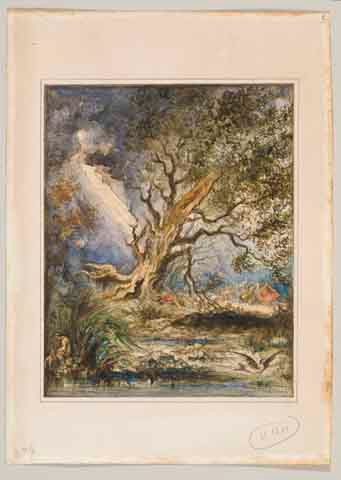

The poem was written during the authoritarian reign of Louis XIV, and there is speculation that the poem could have been an allusion to powerful rulers who think that they are indestructible, but they, too, can fall. Together with the painting by Achille Michallon of The Oak and the Reed, speculation was also turned towards the fall of Napoleon I. However, I don’t buy either of these surmises. In de la Fontaine’s poem, the oak is kind and apprehensive for the reed’s well-being. He has compassion for what he sees as the reed’s weakness. Although his reaction is misguided, it does not appear to emulate a powerful ruler at all. So no, I’m not convinced.

The story does show the mistaken emphasis on strength rather than innovation; the short-sightedness of humans (or trees); and how we cannot see all ends. As the poem had a rather sad ending, I prefer to think on this proverb: “Great oaks from little acorns grow,” and hopefully another great oak will grow from one of its small acorns.