Book IX (Calliope)

“When Alexandros returned and conveyed to Mardonios the response of the Athenians, Mardonios set out from Thessaly and swiftly led his army toward Athens.”

This is the last book in The Histories, and my goodness, I’m glad! I’ve loved this read, but these posts are taking longer and longer to compile. I’m not quite sure why. Is Herodotus’ storytelling getting less compact? Is there just more action happening? Or is my brain beginning an Herodotus-overload?

|

| Public Domain |

Upon receiving word from Alexandros, Mardonios begins his march. The Thessalians gladly allow him to pass through their land but the Thebans try to dissuade his advance, counselling him to bribe the Hellene leaders rather than engage a force that he cannot defeat. Overcome with a raging desire to subdue Athens, Mardonios stubbornly refuses to listen. He moves forward but finds Attica devoid of Athenians because they are all still at Salamis. Sending a messenger to Salamis, Mardonios offers them goodwill and land for their willing subjugation. When an Hellene council member, Lykidas, supports the offer, he is stoned to death by his indignant kinsmen, and their wives, too, stone the wife and children of Lykidas. The puzzle of the Athenians still being in Salamis becomes clear when we learn that they had been waiting for the Lacedaemonian army to come to their aid, but the Lacedaemonians are celebrating festivals and building their wall, delaying their departure. In spite of the Athenians sending a terse message to their compatriots to come to their assistance, the Spartans delay for another ten days and Herodotus is puzzled by their conduct. Are they no longer worried about Persian aggression because their wall is nearly complete? Who knows? Finally Chileos declares that if they do not help the Athenians, they will be in great danger and a Spartan army of 5,000 is launched, led by Pausanias. And so Mardonios’ plan failed, as he was hoping the Athenians would accept his offer, but with the Spartans on the move, he demolishes what is left of Athens and burns it, for it is not a good place for battle, being hostile to calvary with only one small route for retreat. Instead he heads to Thebes. Upon hearing that the Spartan army are in Megara, he turns his troops that way, hoping to demolish them. But receiving word that they have united with the Hellenes, he withdraws to Boeotia, beginning to build a fortification there. A story is told of a banquet in Thebes and a Persian who reveals his belief that few of them will remain alive after this campaign and begins to weep. They cannot reveal their grief because they must follow orders. “The most painful anguish that mortals suffer is to understand a great deal but to have no power at all.”

|

| Plain of Plataea William Miller source Wikimedia Commons |

The Spartans and other Peloponnesians set out from the isthmus and arrive at Eleusis where they are joined by the Athenians who have crossed from Salamis. Taking position in the foothills of Mount Cithaeron, they refuse to come down to the plain and Mardonios sends his forces, led by Masistios (called by the Hellenes, Makistios) to engage them. The Hellenes are able to fend off the attack and Masistios is thrown from his horse and killed. Fighting ensues over the corpse but the Hellenes prevail and emboldened by their victory, move from Erythrai down to Plataea for a better position and better access to water. An argument develops between the Tegeans and Athenians as to who should lead the left wing: the Athenians win because of their graceful argument that they should be the leaders, however they will fight to their utmost wherever they are placed. Now Herodotus describes the deployment of the troops, the Hellenes having 110,000 men, the Persians (barbarians) 300,000. More and more Hellenes join their brothers each day and not much happens as each side is hesitant to begin the conflict because of the oracles they had received at the time of their sacrifices, if either side should initiate battle. Finally, Mardonios becomes impatient and, ignoring the advice of Artabazos and the oracles, prepares his army for battle. Late that night, Alexandros of Macedon rides to the Athenians and tells them of the Persian plans, asking for liberation of Macedon if they succeed in victory. The Hellenes line up their armies with the Persians and after some maneuvering, Mardonios insults the Spartans calling them cowardly and when no response is given, he spoils the water source for the whole Greek army. The Hellenes plan to move their army to an island off Plataea, but after a day of fighting, most of the army goes to Plataea to the sanctuary of Hera. A Spartan commander refuses to budge though, and Pausanias must stay behind to convince him. Finally, Pausanias takes the Spartan army off through the hills while the Athenians turn to march towards the plain. The stubborn Spartan commander, when he sees the army moving away, relinquishes his plan and follows.

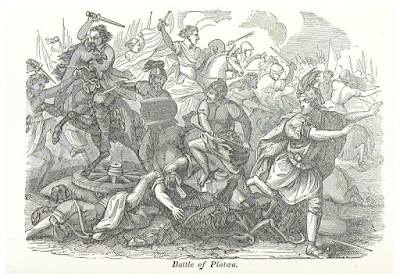

When Mardonios sees the deserted camp of the Hellenes, he disparages the Spartan bravery, calling them cowards. Quickly he marches off after who he thinks are fleeing Athenians, but is really the moving Spartan army. So eager is he to stop their retreat that his army flies off without any organization. Pausanias quickly identifies the pursuit and sends a message to the Athenians to come to their aid, but they are delayed by Greek allies of the Persian king and they are unable to reach the Spartans. At first, the battle seems to swing in favour of the Persians, but soon the sacrifices prove favourable, and lacking the tactical skill, the Persians army begins to fail. Mardonios is killed along with 1000 of his special contingent, the Persians flee and with Artabazos now in control, he takes his forces towards the Hellespont. When other Hellenes hear of the rout, they charge after the barbarians in disorder but many are killed and the rest disperse. The Spartans fight the Persians at their walled camp but as soon as the Athenians arrive, they are overcome and slaughtered. Out of a force of 300,000, a mere 3,000 survive. Herodotus lists the heroes on each side. A concubine woman of a Persian arrives and clasps the knees of Pausanias as a suppliant; he promises protection to her. The Mantineians arrive and are so upset that they missed the battle they return to their homeland and banish their military leader; so too, the Eleans.

|

| Battle of Plataea (1854) John Russell source Wikimedia Commons |

In Plataea, a man named Lampon of Aegina advises Pausanias to win great renown by imitating the Persians’ treatment of Leonidas, by cutting off Mardonios’ head and suspending it from a stake. Pausanias’ response, while polite and diplomatic, echoes of scorn and distaste:

“My friend from Aegina, I commend and appreciate that you mean well and are trying to look out for my future interests, but this idea of yours falls short of good judgment. After you have raised me up on high, together with exalting my homeland and my achievement, you cast me down to nothing by encouraging me to abuse a corpse, claiming that if I did so, I would have a better reputation. But this is a deed more appropriate to barbarians than to Hellenes, though we resent them for it all the same. In any case, because of this, I could hardly please the Aeginetans or anyone else who approves of such deeds as this. It is quite enough for me to appease the Spartans by committing no sacrilege and by speaking with respect for what is lawful and sacred. As for Leonidas, whom you urge me to avenge, I tell you that he and the others who met their ends at Thermopylae have already achieved great vengeance by the countless souls of those who lie here dead. As for you, do not ever again approach me with such a suggestion or try to advise me, and be thankful to leave here without suffering harm.”

The spoils are gathered and one-tenth are given to the god at Delphi. Pausanias is awed by Xerxes’ tent which was left to Mardonios. The corpse of Mardonios disappeared and was presumed buried by an unknown person and Artontes, his son, gave rewards for the treatment. The Hellenes now march against the Thebans who allied with the Persians, asking for them to hand over the conspirators. The Thebans refuse and battle ensues. Finally the leaders are given over, but instead of a trial, Pausanias sends them to Corinth to be executed.

|

| The Serpent Column commemorating the Greek victory moved from Delphi to Constantinople source Wikipedia |

Fleeing Plataea, Artabazos attempts to conceal the truth of the defeat of Mardonios from the Thessalians, in fear for his life. He eventually reaches Asia. Herodotus begins the story of the battle of Mycale in Ionia: Samian envoys approach the Greeks to encourage them to attack the Persians to commence an Ionian revolt. The Greek fleet sets sail, but the Persians retreat, beaching their ships to meet with their land forces leaving the Hellenes to land and prepare for battle. Miracluously, even though the battle of Mycale and the battle of Plataea took place on the same day, the former in the afternnoon and the latter in the morning, news of the victory at Plataea was able to reach the men at Mycale and inspire them. The battle is fierce and the Hellenes put the Persians to flight. The Hellenes counter the plan of the Spartans to evacuate the Ionians to Hellas and the islanders are left as allies of the Hellenes. The Greek fleet then sails to the Hellespont.

While Xerxes is stationed at Sardis, he becomes infatuated with his brother, Masistes’ wife. Unable to find a way to possess her, he marries her daughter to his son and then becomes enamoured of the daughter. When he gives the daughter, Artaynte, a robe woven for him by his wife, the game is up and his wife mutilates the mother. In anger, Masistes leaves to raise a revolt against Xerxes in Baktria, but Xerxes’ forces pursue and kill him.

When the Greek forces find the bridges already broken at the Hellespont, the Spartans return home but the Athenians stay to make trouble for the Chersonese. When the people in the region who were allies of the Persians hear the Athenians are about, they flee to Sestos and the siege of it by the Athenians is arduous until they finally win victory. The Athenians return home with the spoils.

The history ends with a telling of Cyrus who reprimanded Persians who wished to move to another country for the riches. He said:

“because soft places tend to produce soft men, for the same land cannot yield both wonderful crops and men who are noble and courageous in war.”

Wow! I can’t believe that I actually finished! While this book took some concentration to get all the factions and states straight, I’ll always be indebted to Herodotus for giving me a much, much better understanding of the Persian Wars. Now on to Thucydides who, I’ve read, starts where Herodotus left off. Already it’s a much drier read but nevertheless, fascinating.

congratulations for a noble effort! i suppose a historian writing in the 30th c. would describe our era as being even more complex that that of bc Greece, but it still seems pretty dense with action… i remember when i read it, it was hard to believe the numbers of combatants quoted by H… and then i read later that he might have exaggerated the numbers by as much as a factor of ten… i guess we'll never know for sure; anyway, hooray for finishing!

i tried Thucydides once but couldn't make any headway in it; good luck with your efforts, but i have no doubt you'll be successful…

Thanks, Mudpuddle and thanks for being a faithful reader of my loooong posts! 🙂 I was reading up on Herodotus and apparently many archeological finds are confirming his claims, so he's recently more respected. Honestly, I have trouble thinking of him as exaggerating; he was so exacting in so many of his tales. And historians collectively are seeing him as giving a more balanced view of the whole, since he seemed to have an admiration for the Persians and barbarians as well as the Greeks (Hellenes). My "feel" from reading him is that I trust his narrative, or at least believe that he thought he was being as truthful as was possible.

Ah, Thucydides. We shall see if we become friends …… 😉

Wow, congratulations!!! Well done you. I still have 80 pages to go….

that's interesting! tx for the update and verification; that alters my view of the period considerably…

Well, at least I'm ahead of you on something! That's a first …… and possibly a last ……. ha, ha!! I will not mention The Faerie Queene …..!!

Great review(s), Cleo. You are a studious reader of the Ancients. Do you take notes as you read, or do you make summaries after you read sections?

P.S. Augh! You reminded me of that horrid love scheme of Xerxes. So awful.

Thanks, Ruth. I actually don't take notes but I do compile my review as I go.

Men in power tend to do whatever they like. And they have little self control, I assume because they usually are able to have everything their own way. Often I wonder how much they are truly respected. Poor Masistes!

Right – hated for sure, but unfortunately feared. (And not in the reverent way.