As the pilgrims draw lots to determine who will be the first to tell their story, the first draw goes to the Knight.

|

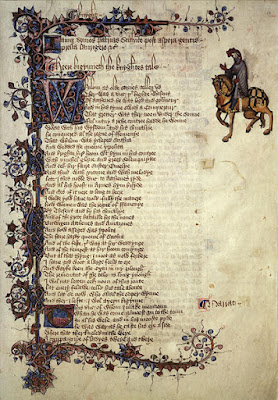

| The first page of The Knight’s Tale source Wikimedia Commons |

The Knight’s Tale

After being appealed to by a number of deposed queens and duchesses from Thebes, King Theseus of Athens attacks the city and gains victory over Creon, King of Thebes. During the fighting, two knights named Palamon and Arcite, are taken prisoner and thrown into a dungeon. Left to rot there forever, Palamon one day spies Emelye, who is as fair as any damsel and the sister of Theseus’ wife Hippolyta, and he falls in love. Arcite, wondering at this cousin’s lovelorn look, spots her too, claims his love of her, and acrimony is born within the love triangle of the cousins.

|

| Portrait of a Knight (1510) Vittore Carpaccio source Wikiart |

Years later, Arcite is released by Theseus upon request of a friend, but is sentenced to exile from which he laments Palamon’s better fate of prison, due to his being able to gaze upon Emelye, whereas Arcite has now been denied that pleasure. Eventually he risks returning to Athens in diguise as a page named Philostratus, who enters Emelye’s household. One day he comes upon Palamon, who has escaped, they begin to fight but are stayed by Theseus who announces that he will set up a grand tournament of knights, and the one who is the victor will win Emelye’s hand in marriage.

Meanwhile, we find, that while Emelye has been the centre of this strife and turmoil, that she actually does not wish to marry either knight. She relates to the goddess, Diana:

“To whom are open earth and sea and sky,

Goddess of maidens, well you know that I

Desire to be a maiden all my life,

And never to be a man’s love nor his wife.

Among your followers I have kept my place,

A maid, in love with hunting and the chase

And to go walking in the greenwood wild

And not to be a wife and be with child;

For nothing will I have to do with man.

Now help me, lady, since you may and can.”

But while Diana could help her, she refuses, stating that Emelye’s destiny has been ordained to marry one of the knights, but which, she will not tell. Emelye submits to her fate with good grace.

|

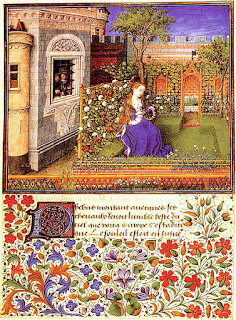

| Emilie dans le jardin observée par Arcitas et Palamon emprisonnés (1460) source Wikimedia Commons |

Palamon prays to Venus for victory, but we get a long description of Arcite in his battle attire before we hear of him offering sacrifices, and for him, it is to the god, Mars; so we have Palamon appealing to the goddess of Love, and Arcite appealing to the god of War. Who do you think will win?

Ah, it appears that Arcite triumphs, bearing down Palamon and his knights, capturing him and taking him to the stake. Venus is shamed with the outcome, but Saturn asssures her that she will also have her desire. But how, with Palamon conquered and Arcite set to wed Emelye?

Well, Arcite has little time to enjoy his achievement. Helmetless, he is pitched to the ground by his horse, landing on his head and receiving mortal wounds. He lasts a short time before succumbing, and Emelye and Palamon are in mourning. But good King Theseus delivers a long speech about the Prime Mover and how all earthly beings must submit to the higher order of things. He blesses the wedding of Palamon and Emelye, and they live happily without jealousy and with extreme tenderness.

One can tell that there is much more to this tale than what is simple cloaking the surface. First, there is the obvious emphasis on fate or destiny or a higher power: Emelye, though she does not wish to marry, readily capitulates to Venus’ edict that she must; and, of of course, while it initially appears to all the people that Arcite will wed Emelye, there is a “blueprint” already in place for everyone’s destiny that man, in his puniness, cannot yet see. A life lived well is to submit to the inevitable, yet take opportunities when they come to you.

|

| Emilie à la chasse assistant au combat entre Arcitas et Palamon Source: Wikimedia Commons |

There is also an emphasis on nature and it’s interaction with man. The General Prologue initially drew us right into Nature and Spring “Whan that Aprille with his shoures sote, The droghte of Marche hath perced to the rote, And bathed every veyne in swich licour, Of which vertu engendred is the flour.” From the sky and nature, we are then taken to be introduced to the earthly pilgrims. In The Knight’s Tale, in the building of the sepulcher for Arcite, there is an obvious battle between nature and man, as Theseus fells the “old oaks” to make a funeral bier:

“You will not hear from me how all the trees

Were felled, nor how the local deities,

Nymphs, fauns, and hamadryads and the rest,

Ran up and down, scattered and dispossessed,

Nor how the beasts and wood birds, one and all,

Fled terrified when the trunks began to fall;

Nor how the ground stood all aghast and bright,

Affronted with the unfamiliar light ….”

There is a continuous tension between man and his environment, again perhaps due to either his lack of foresight, or his inability to understand the grand plan of the Prime Mover.

And, of course, in the battle between Arcite and Palamon and their gods, in spite of the appearance of war winning over love, it is love which achieves the ultimate victory.

I’m certain there are many other themes included, such as pageantry, hierarchical Medevial structure, and not so much the capriciousness of the gods, but the uncertainty of destiny, but I’ve probably explored this tale as much as I can for the first read. One curious point struck me though ….. although this story is set in Greece, the gods are all given Roman names, instead of their Greek ones. I have no idea why, but it is a puzzling choice.

The next tale up, is The Miller’s Tale ……

|

| The Canterbury Tales/ The Brubury TalesProject |

Perhaps Chaucer's conflation of Greek and Roman can be explained by educated medieval folks' fascination with both ancient cultures. I am simply speculating, and I need to dig more into my mind and elsewhere if I hope to support that small-stakes thesis. BTW, which "translation" are your reading? Enjoy the Miller's Tale. Brace yourself!

Hey, R.T.! Yes, the Roman names do have a tendency to be more culturally acceptable during this time period but I thought that because of the setting, they might be a little more realistic. However, I think in Homer's The Iliad and The Odyssey, some older translators use Roman names there as well.

I'm reading translations by Theodore Morrison and an interlinear translation by Vincent F. Hopper. I'm not sure how respected either are. I was going to read Nevill Coghill instead of Hopper, but when I tried him, I didn't really care for his poetry so I "hopped" over to Hopper instead. 😉 Ar, ar! …… Okay, that was a really bad joke. As for The Miller's Tale, it's starting off in a curious manner so I can imagine that I have some surprises in store. 🙂

I loved The Knight's Tale very much, and I liked that idea of the "blue print", which reminds me of course of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy (which Chaucer translated – "Boece" was his title) and the wheel of fortune.

I'm going to read Man of Law later and one thing I'm wondering is how the pilgrims' stories will differ based on their social class. The Knight told a beautiful tale and as a knight he's a respectable sort of chap. The Miller, Reeve, and Cook are tradesmen and working class and their tales are rather salacious. Man of Law will be very well educated I dare say so it will be interesting to see how his differs from the others and what sort of a pattern will be established.

You're so fortunate to have read so much of Chaucer already.

Good point about the tales. With the Reeve's tale, I expected it to be a little cleaner because he almost chastized the Miller about the obscenity of his tale, but then the Reeve's tale ended up being just as coarse. It's nice to have one tale to read this week! 🙂