“Well, Prince, so Genoa and Lucca are now just family estates of the Buonapartes …..”

I am very hesitant to even attempt to review this book. How can one do even the slightest bit of justice to an epic like this? How can one even touch on the depth of the myriad of characters, not to mention communicate the complexities of a war that even the participants had difficulty distinguishing? And how do you review such an epic tale without producing an epic review?

War and Peace follows the lives of five families of Tsarist Russia: the Rostovs, the Bolkonskis, the Bezukhovs, the Kuragins and the Drubetskoys, their interactions and struggles, and the afflictions suffered by each set among the events leading up to and during Napoleon’s invasive campaign in the year of 1812. Pierre Bezukhov is the illegitimate son of a nobleman and, through a series of circumstances, inherits a great fortune. His new position in society chafes against his natural character of simplicity, naiveté, and introspection. The Rostov family is a well-respected family, yet are in financial difficulties. The son, Nikolai, joins the Russian army, his brother, Petya, will soon follow, and their daughter, Natasha, a joyful free-spirit, becomes attached to a number of men throughout the story. Sophia, an orphaned niece, is raised by the Rostovs, and shows a steady and loyal character as she pledges her love to Nikolai early in the novel. Bolkonsky senior is a crochety old count who attempts to control his son, Andrei, and terrorizes his daughter, Maria.

|

Natasha Rostova (c. 1914)

Elisabeth Bohm

source Wikipedia |

And so begins the dance between the cast of characters, sometimes a smooth waltz, and at others a frenzied tango. There is contrast between generations, between old and new ideas, between life and its purpose, yet Tolstoy is adept as showing the gray tones overshadowing the blacks and whites; that situations are not always as they appear.

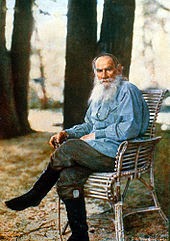

Tolstoy’s highest attribute is his ability to peel off the layers of each person and look into his soul. His characters are crafted with such depth and such human motivations that the reader can only marvel at his skill. And not only can he give birth to such characters, he understands them. The scenes involving the Russian peasantry, who act completely contrary to reason, yet with such humanness, are evidence of Tolstoys profound comprehension of human nature and the human condition.

I love how Tolstoy lets humanity and compassion show through the animosity and the bloodletting of war. One of my favourite characters of the novel was Ramballe, the French officer whom Pierre met in Bazdeev’s house and who showed brotherhood and goodwill despite that fact that, given the circumstances, they should have been pitted against each other as sworn enemies. Originally, Pierre is portrayed somewhat as a bumbling oaf, a man of a lower class who, by luck and circumstances has managed to rise to a position of prestige yet has never been able to cast aside his peasant-like origins. However by his actions in the novel, he becomes admirable, echoing a segment of humanity that shows kindness, goodness, bravery and integrity that shines out from the avariciousness and shallowness of high society.

Tolstoy himself was very ambiguous about his masterpiece stating that it was, “not a novel, even less is it a poem, and still less an historical chronicle.” He believed that if the work was masterful, it could not conform to accepted standards and therefore could not be labelled.

|

|

The Battle of Borodino by Louise-Françoise, Baron Lejeune, 1822

|

“It is natural for us who were not living in those days to imagine that when half Russia had been conquered and the inhabitants were fleeing to distant provinces, and one levy after another was being raised for the desense of the fatherland, all Russians from the greatest to the least were solely engaged in sacrificing themselves, saving their fatherland, or weeping over its downfall. The tales and descriptions speak only of the self-sacrifice, patriotic devotion, despair, grief, and the heroism of the Russians. But it was not really so. It appears so to us because we see only the general historic interest of that time and do not see all the personal human interests that people had. Yet in reality those personal interest of the moment so much transcend the general interests that they always prevent the public interest from being felt or even noticed. Most of the people at that time paid not attention to the general progress of events but were guided by their own private interests, and they were the very people whose activities at that period were most useful. Those who tried to understand the general course of events and to take part in it by self-sacrifice and heroism were the most useless members of society, they saw everything upside-down, and all they did for the common good turned out to be useless and foolish …….. Even those, fond of intellectual talk and of expressing their feelings, who discussed Russia’s position at the time involuntarily introduced into their conversation either a shade of pre tense and falsehood or useless condemnation and anger directed against people accused of actions no one could possibly be guilty of. ……… Only unconscious action bears fruit, and he who plays a part in an historic event never understands its significance. If he tries to realize it his efforts are fruitless. The more closely a man was engaged in the events then taking place in Russia the less did he realize their significance ……….”

|

Napoleon’s Retreat from Moscow

Adolf Northern

source Wikipedia |

Perhaps Tolstoy is showing us that people are imperfect, with human vice and human foibles and that, in spite of trying to find heroics in war, the actions are only the actions of people trying to survive. It is history looking backwards that make the heroes, but in reality, the characters in these trials of life are all people acting out their parts in a very human way. There is no glory in war, only people trying to deal with the circumstances as best they can, and to get by with a little human dignity. Success can be more a matter of chance than planning, and it is often luck or misfortune that places people in either the bright spotlight of fame, or the dark dungeons of villainy.

I know that many people shy away from War and Peace because of its length, and I did too for a long time. Another criticism is that Tolstoy’s “war” parts are monotonous. It certainly is a lengthy novel but by doing some cursive research on this period of Russian history, the reader can gain enough of a base to allow him to relax and be pulled into the story. And by viewing the wars scenes, not only as history, but as a chance to learn from people’s reactions in situations of stress and conflict, I think they can give us more of an insight into human motivations. So pick it up and let yourself be swept away into the Russia Empire of the early 1800s. You won’t be disappointed!

(translated by Aylmer & Louise Maude)