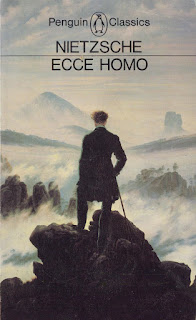

Ecce Homo: “In view of the fact that I will shortly have to confront humanity with the heaviest demand ever made of it, it seems to me essential to say who I am.”

I feel somewhat exhausted. Approaching Ecce Homo with something akin to trepidation, it’s been proven that my expectations are often very accurate. Nietzsche was certainly a trial, but I’m glad that I read Ecce Homo, my first exposure to this singular German philosopher. Wow, Nietzsche would hate that description. He despised Germans and felt philosophy was a fraud. In any case, he didn’t like most things, so any way I described him, I’d be in danger of his patronizing, scathing invective.

Ecce Homo, or How One Becomes What One Is (Wie Man Wird, Was Man Ist) was the last book that Nietzsche wrote before his death and gives insight into the man, his ideas and his works. The words “Ecce Homo” are taken from the words Pontius Pilate used when he delivered Jesus, scourged and bleeding, to a riotous crowd right before he was taken to be crucified. Nietzsche hated Christianity because he felt that it was the mechanism for the function of society and, therefore, was responsible for everything that was wrong with it.

Yet while the book gives enlightenment, it does so from Nietzsche’s perspective, words coming from a man who already seemed in the throes of the mental illness that would bring about his death. It’s certainly helpful to see it in this light.

Why I Am So Wise

Nietzsche is better than everyone else in the world. He is so incredibly wise and we are such small, insignificant beings compared to him, with nothing in particular to add to the benefit of humanity, that he can hardly stand to be in our presence. Lest you think I’m being too hard on him, let Nietzsche speak for himself:

” ….. I have an instinct for cleanliness that is utterly uncanny in its senstivity, which means that I can physiologically detect —- smell —- the proximity or (what am I saying?) the innermost aspect, the ‘innards’ of every soul …… I am already conscious of the large amount of concealed dirt at the bottom of many a nature, perhaps occasioned by bad blood but whitewashed over by upbringing. ……. natures like this which are unconducive to my cleanliness feel the circumspection of my digust on their part, too; it does not make them smell any more pleasant ……. impure conditions are the death of me ………. This makes dealing with people quite a trial to my patience; my humaneness consists not in sympathizing with someone, but in putting up with the fact that I sympathize with them …… My humaneness is a constant self-overcoming …….”

|

Ecce Homo (1964-67)

Salvador Dali

source Wikiart |

There is more blather stating that compassion, rather than being a virtue, is a weakness, and he references his work, Zarathustra, for proof (in this I believe Nietzsche misses making the distinction between false compassion and true compassion); and labelling rudeness as one of the foremost virtues (again, he muddles benevolent frankness with lack of resolution and fortitude to deal with issues).

He announces his penchant for war, or attack, and lists his rules of war:

- He attacks only causes which are victorious

- He attacks causes only when there are no allies to be found

- He never attacks people

- He attacks things only when all personal disagreement is ruled out

He claims that he can attack causes with impunity, and that there are no hard feelings from the victim, yet in his next chapter he states, “May I make bold as to intimate one last trait of my nature which causes me no little trouble in my dealings with people?,” indicating that his relationships are not so harmonious as he’d like to believe.

Why I Am So Clever

I seriously asked myself if I really wanted to know why Nietzsche thought himself so clever, but, foolish me, I decided to keep on reading.

Nietzsche lists the reasons for his cleverness at the beginning of this section:

- he has not squandered himself

- he has no personal experience with true religious difficulties

- he is entirely at a loss to know how sinful he is supposed to be

Higher educations causes one to lose sight of realities and Nietzsche then begins to take pot-shots at the German education system, which regresses to insulting German culinary tradition. How we got there, I’m uncertain. He then conducts a detailed investigation into:

- nutrition

- place

- climate

- relaxation

Within these four topics, Nietzsche likens reading to letting an alien climb over your wall; claims he reads the same books because he is opposed to new books by instinct; states everywhere that Germany extends, it ruins culture; that we are all afraid of truth; and that Wagner to him, is like hashish. It sounds bizarre and, quite frankly, is, but there are certainly some interesting ideas in Nietzsche’s convoluted onslaught of aberrant thought.

He claims that he now cannot avoid the question how to become what you are, but then digresses, and I can’t find anywhere where he answers it.

And asked why he concentrates so much on the small issues of above, Nietzsche alleges that to-date everything that man had deemed important is, in fact, lies because we have searched for divinity in human nature. We must start relearning and therefore, we must begin with the basics.

Why I Write Such Good Books

“I am one thing, my writings are another.”

Nietzsche is resigned to the fact that no one will be able to understand his writing, feeling no ill-will towards anyone for their lack of intellect.

” …. in other words experiencing —- six sentences of it [Zarathustra] raises you up to a higher level of mortals than ‘modern’ men could ever reach ….”

Some day, there will be universities dedicated to understanding his works. No one has experienced what Nietzsche has, and therefore is it not understandable that no one can comprehend his genius? Oh here, let me allow Nietzsche to speak for himself:

“I know my prerogatives as a writer to some extent; in certain cases I even have evidence of how much it ‘ruins’ people’s taste if they get used to my writings. They simply can no longer stand other books, least of all philosophy books. It is an unparalleled distrinction to step into this noble and delicate world — for which you must not on any account be a German; ultimately it is a distinction you need to have earned …… I come from the heights to which no bird has yet flown, I know abysses into which no foot has yet strayed. I have been told it is not possible to let a book of mine out of one’s hands —- that I even disturb sleep …… There is definitely no prouder and at the same time more refined kind of book: here and there they achieve the highest thing that can be achieved on earth, cynicism; you must tackle them with the most delicate fingers as well as with the bravest fists.”

Nietzsche then outlines each of his books, spending most of his time lauding their brilliance, mentioning the few geniuses who have enjoyed them, and condemning everyone who disliked them.

The Birth of Tragedy: “It is politically indifferent —– ‘un-German’ in today’s parlance —- it smells offensively Hegelian, and in just a few phrases it is tainted with the doleful scent of Schopenhauer. An ‘idea’ — the Dionysian/Apollonian opposition —- translated into metaphysics, history itself as the development of this ‘idea’; in tragedy the opposition sublated to become a unity form this point of view things that had never looked each other in the face before suddenly juxtaposed, illuminated, and understood in the light of each other …..”

The Untimelies: The Untimelies can also be translated as “Thoughts out of Season”, “Unmodern Observations” or “Unfashionable Observations”. In this writing, Nietzsche draws his rapier and launches four attacks:

First, an attack on the German education system. I found that this was the first time I actually agreed with Nietzsche. He purported that there was no evidence at all that Germany’s military success was a result of their education. The school system in America is apparently an offshoot of this Prussia model. I found an interesting article about it here. One of my favourite authors, John Taylor Gatto, talks about this model in his book, The Underground History of American Education. I highly recommend it.

The second attack is titled, On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life. Nietzsche warns of the dangers of “our kind of scientific endeavour, what there is in it that gnaws away at life and poisons it —- life made ill by this dehumanized machinery and mechanism, by the ‘impersonality’ of the worker, by the false economy of the ‘division of labour’. The end, culture, is lost — the means, modern scientific endeavour, barbarizes ….” Hmmm ….. is it possible that I might again agree with Nietzsche? That would be just too weird.

The third and fourth Untemelies, titled Schopenhauer as Educator and Richard Wagner in Bayreuth, give an impression of “a higher conception of culture, towards the restoration of the concept ‘culture'” in which two images are set, having the highest contempt for everything around them that is synonymous with the present culture. I doubt that I’d side with him here.

Nietzsche appears to take great joy in upsetting everyone around him.

Human, All Too Human: With Two Continuations:

Subtitled A Book For Free Spirits, Nietzsche claims in this writing that he liberated himself from idealism and is “a spirit that has become free, that has seized possession of itself again.”

I wasn’t quite clear as to what exactly this work was about, due to Nietzsche’s ambiguity and his habit of digression, but it appears that he mentions things favourable to Voltaire, and addresses his break with Richard Wagner. Why am I not surprised that he extols the thoughts of Voltaire?

The work apparently evolved out of some mental crisis that Nietzsche experienced during the Bayreuth Festival when he felt a “profound sense of alienation” and went off into the forest before being coaxed back by his sister.

Daybreak: Thoughts on Morality as Prejudice

Nietzsche states that this book commenced his war against morality. Again, Nietzsche commends his work and genius, rather than getting to the meat of his ideas.

“Even now, if I encounter the book by chance, practically every sentence becomes a tip with which I can pull up something incomparable from the depths once again: its whole hide quivers with the tender shudders of recollection ….”

But finally Nietzsche gets to a description of what he believes is its value:

“In a revaluation of all values, in freeing himself from all moral values, in saying ‘yes’ to and placing trust in everything that has hitherto been forbidden, despised, condemned. This yes-saying book pours out its light, its love, its delicacy over nothing but bad things, it gives them back their ‘soul’, their good conscience, the lofty right and prerogative of existence.”

Good grief! You want to counter this statement but where do you start? Does he think that there have been no societies that have tried to live without morality? Is this morality-proper or Nietzsche’s type of morality? Can one truly escape some sort of morality?

The Gay Science: This title is developed out of the Provençal expression which is used to describe the technical skill of writing poetry, as Nietzsche describes it, “almost every sentence here profundity and mischief go tenderly hand in hand.” The quality of the Provençal style shows “unity of singer, knight, and free thinker which distinguishes the marvellous early culture of the Provençal people from all ambiguous cultures ….”

Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book For Everybody and Nobody: Again, it’s best for Nietzsche to describe this, in his often lovely prose ~ what it means, however, one is often left wondering ….

“Aphorisms quivering with passion; eloquence become music; lightning-bolts hurled on ahead towards hitherto unguessed-at futures. The mightiest power of analogy that has yet existed is feeble fooling compared to this return of language to its natural state of figurativeness —- And how Zarathustra descends and says the kindest things to everyone! How he tackles even his adversaries, the priests, with delicate hands and suffers from them with them! —- Here man is overcome at every moment; the concept of ‘overman’ has become the highest reality here — everything that has hitherto been called great about man lies at an infinite distance below him. The halcyon tone, the light feet, the omnipresence of malice and high spirits and everything else that is typical of the type Zarathustra has never been dreamed of as essential to greatness. Precisely in this extent of space, in this ability to access what is opposed, Zarathustra feels himself to be the highest of all species of being; and when we hear how he defines it, we will dispense with searching for his like.”

I won’t sport with your intelligence in continuing to relate just how much more knowledgable and astute Zarathustra (and therefore, Nietzsche) is than you will ever be.

Beyond Good and Evil: If Nietzsche doesn’t catch any “fish” with his works, what could that mean? The cause? Is it perhaps because his arguments don’t make sense or people can’t relate to his delivery? No! According to Nietzsche, it means that there simply weren’t any fish to be caught.

This book is “a critique of modernity, not excluding the modern sciences, the modern arts, even modern politics, together with pointers towards an opposing type, as unmodern as possible, a noble, yes-saying type ….. refinement in form, in intention, in the art of silence is in the foreground; psychology is handled with avowed harshness and cruelty —- the books is devoid of any good-natured word …..”

Genealogy of Morals: A Polemic:

A book of three essays:

- the psychology of Christianity

- the psychology of conscience

- where the immense power of the ascetic ideal springs from

This actually sounds somewhat interesting to me.

Twilight of the Idols: How to Philosophize with a Hammer:

Nietzsche recommends starting with this work. It’s a short book but “there is nothing richer in substance, more independent, more subversive —- more wicked …”

Nietzsche is the first to have “the yard-stick of truths in his hand.” He is the evangelist to truth, and everyone was lost before him.

The Wagner Case: A Musician’s Problem: To read this properly, you need to feel as though music is the history of your own suffering. I think that this writing deals with his split from his friend, Richard Wagner, a well-known German composer, but Nietzsche launches a scathing invective against, I’m assuming, the ideals that Wagner supported. He castigates Germans for many things, wrapping up his ire in their great cultural crimes. He attacks Martin Luther along with Leibniz and Kant. In fact, Germans have “robbed Europe of its meaning, its reason…”

Why I Am A Destiny

Nietzsche is terrified that one day he will be called holy. But, he admits, his “truth is terrifying, for lies were called truth so far. —- Revaluation of all values: that is my formula for the highest act of self-reflection on the part of humanity, which has become flesh and genius in me. My lot wills it that I must be the first decent human being, that I know I stand in opposition to the hypocrisy of millennia ….. I was the first to discover the truth, by being the first to sense — smell — the lie as a lie ….. My genius is in my nostrils.”

What follows is more exaltation of evil and lying, and conversely Nietzsche advocates war against the good, benevolent, the beneficent, and Christian morality. More invectives against Christianity follow, the content of which makes me wonder if Nietzsche really had an issue with Christ, or simply with the way Christianity had been presented to him. In any case, it really doesn’t matter. At this point Nietzsche had drained me, and I predict that I’d have an issue reading any work longer than this book of his, which is only 138 pages. He signed this work ~ Dionysus against the crucified one ~ Nietzsche aligned himself with the early Greek philosophers and thought of himself as a modern-day Dionysus.

|

Bacchus (or Dionysus – 1596)

Caravaggio

source Wikiart |

Never mind Dionysus —– Nietzsche is the consummate Narcissus. He placed himself in the position of God; everything was measured by his own thoughts and emotions, and judged accordingly. Since he was so much above everything and everyone, is it any surprise that all fall short of his ideal? Perhaps that is nothing, and for a great philosopher is understandable. Yet the contempt and the disparagement that he exhibits towards nearly everyone, not only severely undermines much of his philosophy, but also twists his ideas into a mass of writhing snakes where one is at a loss to find the proper head and tail to each.

I found some of Nietzsche’s ideas fascinating, but as soon as I started to read his arguments that developed those ideas, he often lost my interest. Not only were his disputations littered with self-praise, ambiguity and circumlocution, he often didn’t make sense, or perhaps I should say that, in this book, his explanations didn’t go far enough. He also spoke from a very ethnocentric point-of-view. Although he believed that he borrowed ideas from the ancient Greeks, almost everything he criticized was German, and everything he wanted to fix related to German society. I’m not sure how well some of his arguments would hold up in other countries, but my brain is too done to wonder about this ——- no, my brain is not tired because it explored wonderfully deep amazing thoughts; it’s tired as if it’s had to put up with a recalcitrant child for the last couple of weeks. And so ends my first experience with Nietzsche.

I am quite enjoying my WEM Project. It’s forced me to read some books that I probably wouldn’t have touched otherwise. I didn’t particularly enjoy Nietzsche but look at the length of my review! He at least inspired something, even though it wasn’t admiration.