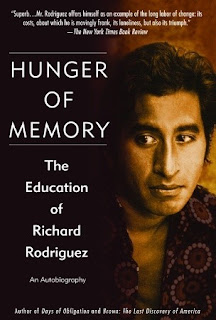

“I have taken Caliban’s advice. I have stolen their books. I will have run of this isle.”

With the first sentence, in his allusion to Shakespeare’s, The Tempest, Richard Rodriguez sets the tone for his memoir, depicting his life as the son of Mexican immigrants. Is he a monster, an outcast who will use his adversaries’ own weapons to gain power, an identity, and a place in the kingdom?