Before we get to the prologue of this tale, there are Words of the Franklin to the Squire and of the Host to the Franklin, where the Franklin commends the Squire for the spirit in which he told his tale, and that his eloquence is surprising considering his youth. He deprecates his own son until the Host interrupts to urge him to tell his tale.

The Franklin begs pardon for his lack of education and he, therefore, cannot adorn his words with the “colours of rhetoric”, but still he will do his best with his story.

The Franklin’s Tale

In Brittany, or in, at that time, Armorica, there lived a knight, Arvéragus, who held a deep abidding love for a lovely, high-born lady, Dorigen. Alas, he neared despair of his love being returned due to her high status in society, but she saw the honourable worth of Arvéragus, and the two were joined in marriage. He gave his promise that he would never show jealousy nor impose his will upon her, and, in turn, she pledged humbleness and faithfulness to her husband. The Franklin next gives a quite wonderful description of love, and how to temper it for a successful relationship:

“Lovers must each be ready to obey

The other, if they would long keep company.

Love will not be constrained by mastery;

When mastery comes the god of love anon

Stretches his wings and farewell! he is gone.

Love is a thing as any spirit free;

Women by nature long for liberty

And not to be constrained or made a thrall,

And so do men, if I may speak for all.

Whoever’s the most patient under love

Has the advantages and will rise above

The other; patiences is a conquering virtue,

The learned say that, if it not desert you,

It vanquishes what force can never reach;

Why answer back at every angry speech?

No, learn forbearance or, I’ll tell you what,

You will be taught it, whether you will or not.

No one alive — it needs no arguing —

But sometimes says or does a wrongful thing;

Rage, sickness, influence of some malign

Star-constellation, temper, woe or wine

Spur us to wrongful words or make us trip.

One should not seek revenge for every slip.

And temperance from the times must take her schooling

In those that are to learn the art of ruling.”

Middle English:

For o thyng, sires, saufly dar I seye,

That freendes everych oother moot obeye,

If they wol longe holden compaignye.

Love wol nat been constreyned by maistrye.

Whan maistrie comth, the God of Love anon

Beteth his wynges, and farewel, he is gon!

Love is a thyng as any spirit free.

Wommen, of kynde, desiren libertee,

And nat to been constreyned as a thral;

And so doon men, if I sooth seyen shal.

Looke who that is moost pacient in love,

He is at his avantage al above.

Pacience is an heigh vertu, certeyn,

For it venquysseth, as thise clerkes seyn,

Thynges that rigour sholde nevere atteyne.

For every word men may nat chide or pleyne.

Lerneth to suffre, or elles, so moot I goon,

Ye shul it lerne, wher so ye wole or noon;

For in this world, certein, ther no wight is

That he ne dooth or seith somtyme amys.

Ire, siknesse, or constellacioun,

Wyn, wo, or chaungynge of complexioun

Causeth ful ofte to doon amys or speken.

On every wrong a man may nat be wreken.

After the tyme moste be temperaunce

To every wight that kan on governaunce.

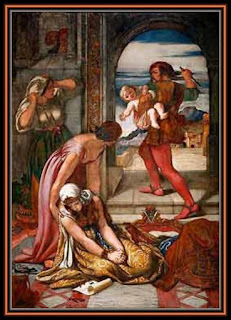

Arvéragus and Dorigen lived in wedded bliss until one day Arvéragus decided to leave to win renown and honour in Britain. Two years he will be gone, and Dorigen wept and bemoaned the loss of her husband every single day. Unbeknownst to Dorigen, a handsome and lively squire, Aurelius, was sick with love for her, and finally confessed his suppressed passion. While Dorigen repeated her vow to be a faithful wife, in a moment of thoughtless gaiety, she promised her love if he was able to remove all the rocks from the coast of Brittany, an impossible task. Yet she did not reckon on Aurelius’ determination and after praying to the gods and two years of bemoaning his hopeless assignment, he found a conjuror who completed the task. When he informed Dorigen of his success, she was brokenhearted, for she had thoughtlessly broken the promise to her beloved husband. She decided that she must die rather than defile her love, and sited various instances from ancient accounts of women who took this recourse. However, when Arvéragus returned home, she confessed her transgression to him, whereupon he stated that she must keep her promise, no matter what pain it would bring them. Yet when Aurelius saw her woe and learned of the noble deed of Arvéragus, he released the lady from her promise, even though he was left with an enormous debt payable to the conjuror. Yet fate was kind, in this case, and the conjuror immediately forgave the debt, saying that he had been paid with Aurelius’ moving story.

This tale is possibly based on a similar one in Boccaccio’s The Decameron (Tenth Day, Fifth Tale), but the removal, or apparent removal of the rocks echo Merlin’s magical moving of the rocks accounted in The History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey Monmouth.

This tale was particularly moving because of the themes of loyalty, patience and keeping one’s promise. My favourite tale so far (do I keep saying that?)